The rifle volley shattered the quiet in the cemetery and made me jump. Immediately, the synchronized snick of bolts being worked, empty shells clinking on the ground, and the order, “Ready, fire!” and another cracking volley.

I was ten at the time.

I scrambled between adult legs to snatch one of the still warm brass casings. I hardly noticed that the volley was being fired over the grave of my great uncle, Theodore Williams, who was killed in WWI.

Each year of my 1940’s childhood in tiny Thomaston, Maine, a military unit along with marching band formed up on Armistice Day (Nov. 11) and marched through town to the cemetery. I thrilled to this little martial spectacle. The street was lined with crowds, and we kids ran along beside, dodging through grown-ups wearing red paper poppies, the symbol of remembrance of those who died in the Great War. (Not until 1954 was Armistice Day changed to Veteran’s Day).

My great aunt, Theodore Williams’ sister, lived with us and told me that her brother had been killed in the war, but she provided no details, and I didn’t pay much attention. This was shortly after WWII ended, and my best friend and I were engrossed in playing with a trunk full of Wehrmacht memorabilia brought back by his wounded brother. And movies like John Wayne’s The Sands of Iwo Jima had focused my interest on WWI’s sequel.

But as we embarked on The Great War Project, I began to wonder about the death of this great uncle I never knew.

It turns out that he was involved in two of the most significant battles of the war. One of them was the first major engagement fought by Americans and the second, in which he was killed, is viewed by many historians as the hinge point in the war.

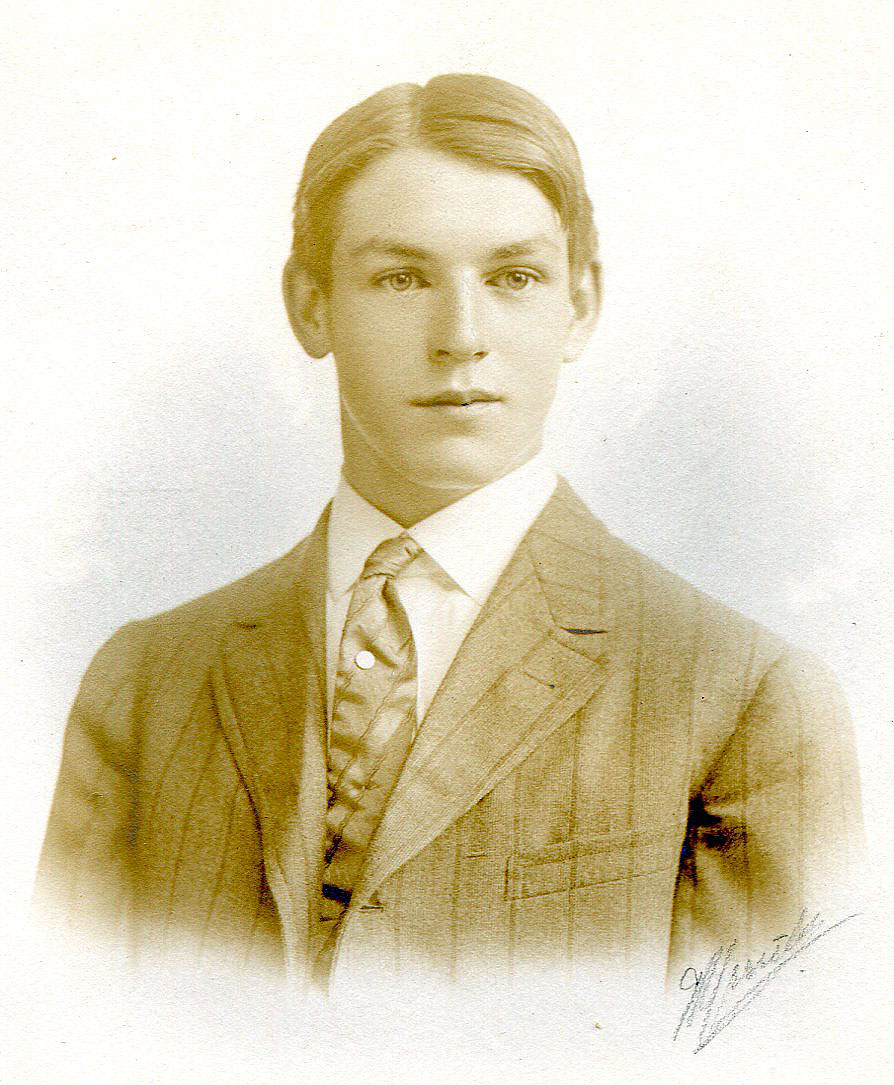

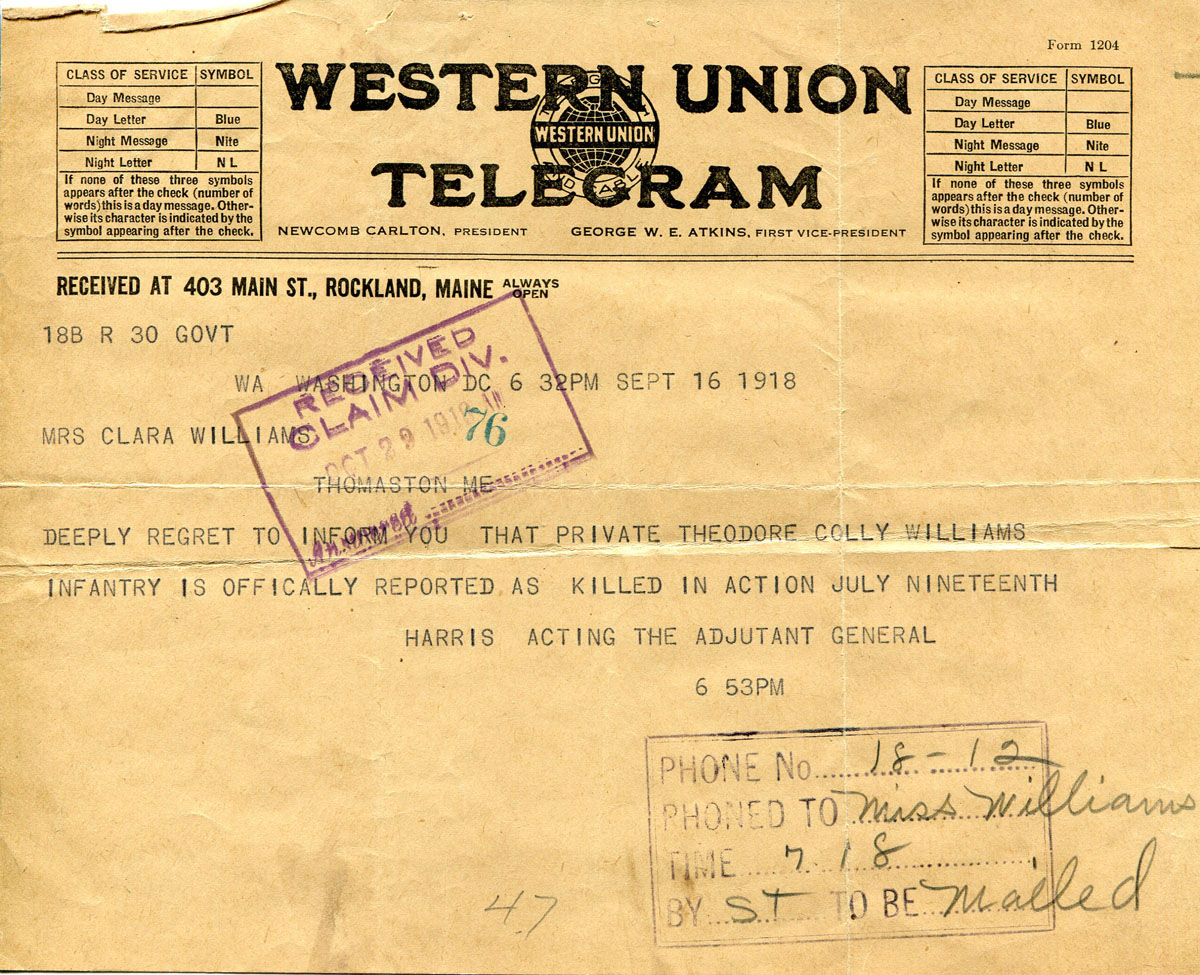

When I started my search for Uncle Theo Williams, all I had to go on was a picture and a telegram to my great grandmother announcing that he had been killed in World War I. The picture and the telegram had been found and sent to me by my sister, Lisa.

So the first place I went was Ancestry.com to look for information about Theo’s military history. They have a military records section where I entered what little information I had about him. I assumed he had enlisted in Maine, his home state. I found his name in a list of Maine residents who served in the war, but that was all.

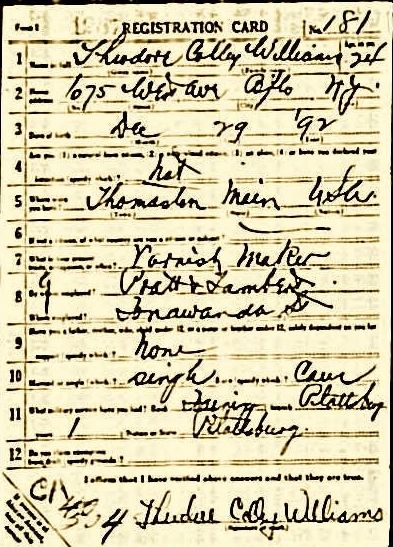

I am easily frustrated with difficult searches, so I began to look elsewhere. Then one of my colleagues on this project said she had found his draft card on Ancestry.com.

I retraced her steps, and sure enough, there it was. But it showed that he was inducted in Buffalo, New York, not Thomaston, Maine, his hometown. The draft card said he was a varnish maker at the Pratt and Lambert plant there.

I retraced her steps, and sure enough, there it was. But it showed that he was inducted in Buffalo, New York, not Thomaston, Maine, his hometown. The draft card said he was a varnish maker at the Pratt and Lambert plant there.

This was a surprise. Theodore was the son of a famous (some would say infamous) Thomaston sea captain, Thomas Colley Williams. Captain Williams had sailed 4-mast tall ships to Shanghai, Liverpool and around Cape Horn many times. He had a reputation as a bully and the San Francisco maritime museum says he shanghaied crewmen in San Francisco. He was a fairly wealthy man.

So why was his son out in Buffalo making varnish? I may never know the complete answer but a little more research showed that the president of Pratt and Lambert was also from Thomaston. Perhaps Theo had been sent out as an apprentice in a plant where he had a friend at the top. In any case, Theo and several other Pratt and Lambert employees were inducted at the same time.

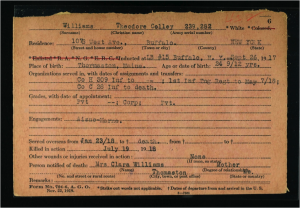

So I had a draft card, but that offered little information about Theodore Williams following his induction. How and where did he get killed? I had to know the names and numbers of the various outfits he served with after joining up in Buffalo. So I went back to the well at Ancestry.com. Ancestry links to many data bases concerning military service. In one of those I discovered a record of his service.

From this I learned when he went into the Army and the outfit he was with when he was killed. Also that he went from private to corporal –then back to private.

At the same time my sister Lisa had hit pay dirt when she again poked around in old family papers.

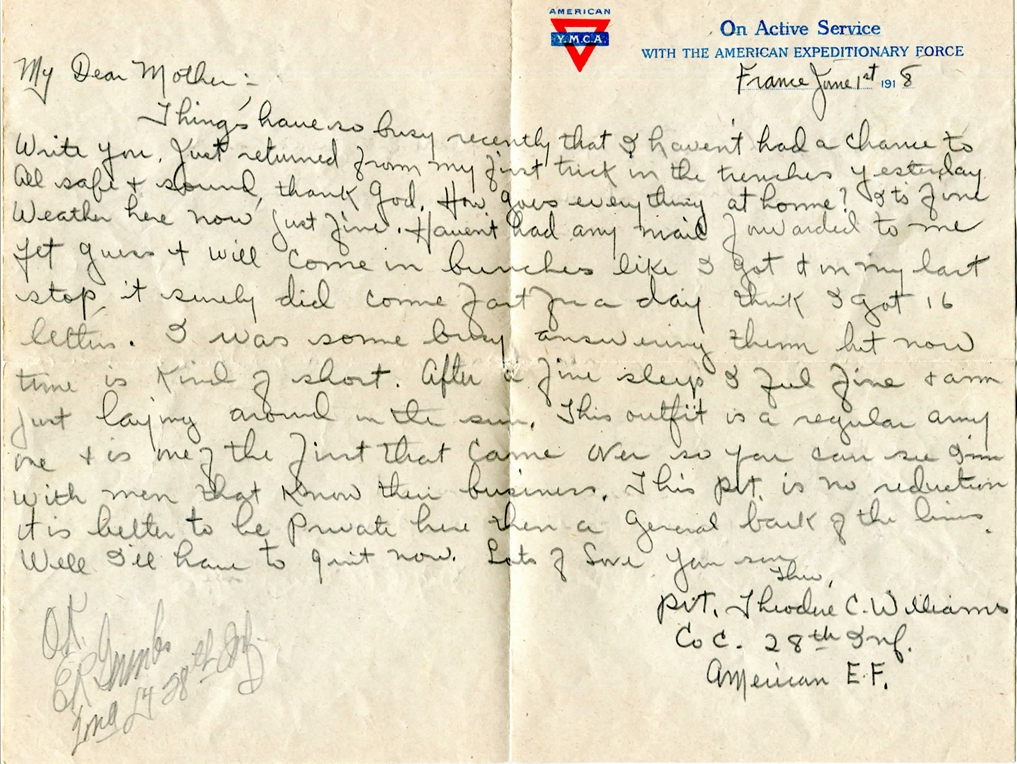

There were two letters from Theodore from France, and several documents revealing that his mother and his sister had embarked on an intensive search to find out how and where he had been killed and where he was buried.

That this was necessary says something about the confusion surrounding the thousands of dead in the battles he fought in. And there’s the obvious irony that I was doing the same thing nearly a hundred years later.

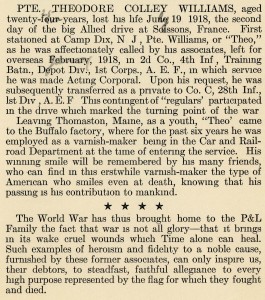

One document my sister found was a tribute to the Pratt and Lambert employees who had been killed in the war. Theo was one of four.

So Corporal Williams had requested a transfer to an outfit of tough regulars, the 28th Infantry, part of the First Division, known as the Big Red One. To do that he suffered a reduction in rank, back to private. The penciled corrections were made by Theo’s sister, my great aunt. The 28th’s Company C turned out to be involved the two of the most crucial, brutal battles fought by the Doughboys.

With the records and letters I had at hand, I knew that Private Theodore Williams, at his own request, had been transferred to Company C of the 28th Infantry Regiment of the First Division. The First Division, which became known as Big Red One, was the first to be formed in the run-up to America’s involvement in the Great War.

About half of soldiers in the 28th Regiment were regular Army; that is, they were enlistees who were not greenhorns. Perhaps Theo knew that they would be among the first Americans to be called into battle. They were.

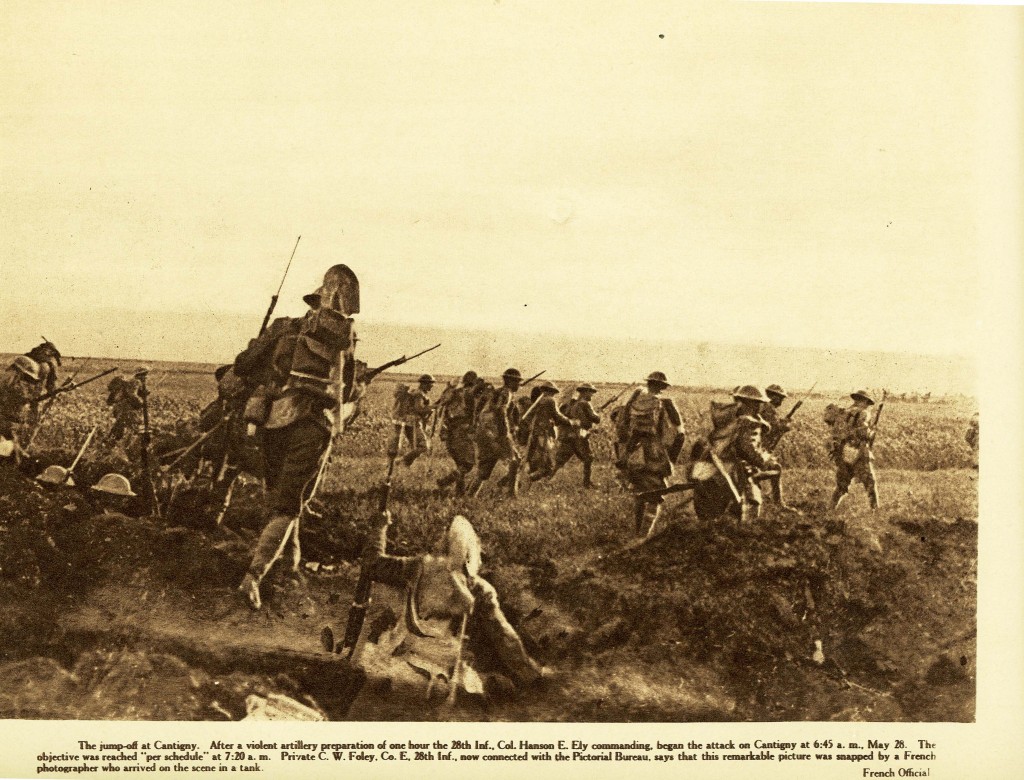

At this point my research I had to turn to history books about the Doughboys in order to find out about the First Division. One historian says the First Expeditionary Division could well have been called the First Experimental Division, because the U.S. Army had not been engaged in large scale warfare since the Civil War. An American division contained roughly 27,000 men and a company 250 men. The First Division trained in France, at first away from the lines and then briefly holding “quiet” lines where they suffered only a few casualties. On April 17, 1918, the First began its 22-mile march to the active front under backbreaking packs weighing over 70 pounds. The earliest bloody experiment for the First Division would be the battle of Cantigny.

Cantigny was a small, battered village that had changed hands several times. It had little strategic value, but was seen by the British and the French, who were skeptical of Doughboy combat skills, as a test of the new American troops. Lawrence Stallings, author of The Doughboys, put it this way: “The Big Red One, officers and men, were all aware that this was a world premiere, albeit in a village theatre.”

At first the attack went well, but then the Americans were subjected to intense artillery bombardment and three German counterattacks. General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, insisted that the beleaguered Doughboys hold their positions at all costs. The battle lasted three days and the costs were high: two hundred officers and men killed or missing and 669 wounded.

Lt. Col. George Marshall, operations officer of the First and later author of the Marshall Plan following WWII, admitted that “the losses we suffered were not justified by the importance of the position itself.” But the losses did prove to the Allies the steadfastness of the Doughboys.

Along with George Marshall, a couple of other notable figures served in the 28th Regiment: Private Sam Ervin, later a key senator in the Watergate hearings, and Col. Robert M. McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, who later established the First Division Museum in Wheaton, Illinois.

Which brings us back to Private Theodore Williams, my great uncle. The First Division Museum has a research arm, so I wrote them and asked what they could find out about Uncle Theo.

A surprise response quickly came back from Eric Gillespie, director of the Research Center. Turns out Private Williams had been cited for his performance at Cantigny.

“The Regimental Commander cites the following officers and men of the command for conspicuous gallantry in action during the operations connect with the capture and defense of Cantigny, May 27th-31st, 1918: PRIVATES CARL H. HALLEY, HERMAN GILHAM AND THEODORE C. WILLIAMS, Company “C”, 28th Infantry, ‘These three men were assigned to the company just before the attack. They formed a part of a carrying party to BN “A” Strongpoint. The party was shot up and the sergeant commanding it wounded. Nevertheless, the above mentioned men carried on with their work, without a leader, all thru the action, materially aiding the defense of our new position.’ ”

A “carrying party” referred to in the citation brought rations and ammunition to those on the front lines. Unlike men in trenches and shell craters, they were completely exposed as they raced across open fields with their loads.

Combined, Eric Gillespie says today, “I believe that your late great-uncle would be eligible for a Silver Star Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster.”

He makes the point that he is with regular army men “who know their business.” But there is no reference to the searing battle he has just been through. And then he mentions the reduction in rank that came with the transfer to a different unit, a transfer he requested: “It is better to be a private here than a general back of the lines.” Theodore wrote this extraordinarily understated letter to his mother just one day after the brutal action at Cantigny.