Einstein Wants End to War; Lenin Sees Civil War Spreading

Special to The Great War Project

(12-21 November) Many significant developments during these days across the broad bloody tapestry of the war, one hundred years ago.

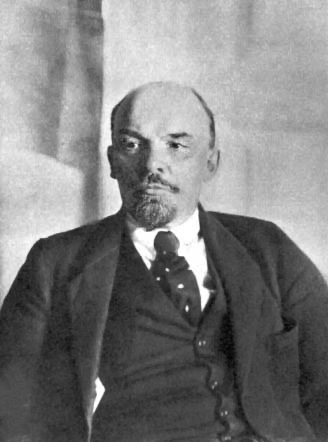

Two powerful individuals are watching the war spread: the Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin from his safe perch in Switzerland and Albert Einstein from inside Germany.

“The epoch of the bayonet has begun,” writes Lenin, who predicts the coming of a civil war between the classes, and according to historian Martin Gilbert “the triumph of the working class,” as he watches a one-day workers’ strike unfold in Petrograd on November 12th.

Just a few days later, Albert Einstein and other prominent German intellectuals create the New Fatherland League. It appeals,” reports Gilbert, “for the “prompt achievement of a just peace without annexations” and for the creation of an international organization “that would have as its aim the prevention of future wars.”

The League has little impact.

Another founding member recalls years later how she once approached Einstein “when I was depressed by the news of one German victory after another and the resultant intolerable arrogance and gloating of the people of Berlin.”

“What will happen, Herr Professor?” I asked anxiously.

Einstein looked at me, raised his right fist, and replied: “This will govern.”

Nevertheless the battles roll on.

On November 18th a century ago on the Eastern Front, a huge battle is emerging at the Polish city of Lodz. A quarter of a million German troops nearly surround the city, defended by 150,000 Russian troops.

“The battle for Lodz was on a gigantic scale,” writes Gilbert. The Russians set a trap for the Germans, but the Germans break out. The Germans are unable to counter with their own unsuccessful trap for the Russians. “The energies of both armies flagged, worn out by defeats, fighting, and the vileness of the swampy country.”

Nature becomes the decisive factor. That should not be a surprise.

“The frost was becoming more severe,” writes one historian, “with icy winds, and the temperature at night fell to within ten degrees of zero. The approach of winter laid its paralyzing hand on the activity of German and Russian alike.”

Another diarist, a British officer observing the activities of the Russian forces at Lodz, writes: “The necessity for rapid refilling of casualties owing to the enormous losses of modern war has been, I fear, lost sight of in Russia, and if we have to advance in the winter, our losses will be three times as great.”

“We have lost several men frozen to death in the trenches,” he writes.

Elsewhere small but significant developments in the battle for the air, on these days a century ago. “On November 21st,” reports historian Gilbert, “three British aircraft carried out the first long-distance bombing raid of the war when they flew from the French town of Belfort to the German Zeppelin sheds at Friedrichshafen” in Germany.

Each British aircraft carries four bombs. One Zeppelin is damaged. One British flyer is forced to land, and he is attacked by German civilians.

He is rescued by German soldiers.