Wilson is Silent on Lusitania disaster;

New Allied Losses on Western Front

Special to The Great War Project

(8-11 May) In the aftermath of the Lusitania disaster, many questions arise that do not yet have answers.

One of the most important, and most controversial, is why the British Admiralty offered no convoy to protect the ship when it neared the British Isles, where it would be most vulnerable.

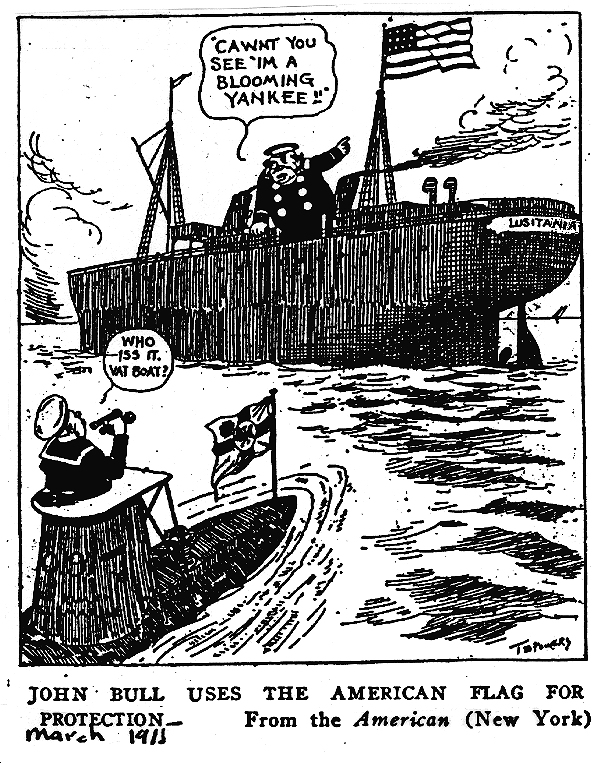

One of the suspicions that takes hold is that the Lusitania disaster is part of a British plan to get the United States into the war, on the side of the Allies of course.

This is certainly on the minds of both American and British leaders. In fact President Wilson’s closest confidante, Colonel Edward House, is in London on the very day the Lusitania is attacked. He meets with the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey.

“We spoke,” House writes in his diary, “of the probability of an ocean liner being sunk and I told him if this were done, a flame of indignation would sweep across America, which would in itself probably carry us into the war.”

Later that day, House meets with King George at Buckingham Palace. The two also consider the possibility that a German submarine might sink a trans-Atlantic ocean liner. House reports in his diary that the King proposed another chilling possibility:

“Suppose they should sink the Lusitania with American passengers on board?”

This is precisely what occurs just a few hours later off the coast of Ireland, and it is no exaggeration to say that it shocked the United States.

“The sinking of the Lusitania,” writes historian Arthur Link, “had a more jolting effect upon American opinion than any other single event of the war…. It confirmed what the minority of pro-Allied extremists had been saying all along – that Germany had in fact run amuck and was now an outlaw among civilized nations.”

“It marked the dividing line between the time when there was no organized and vocal sentiment for American participation and the time when that sentiment existed in substantial measure.”

When House returns to the United States, reports Link, he advises the President that the United States “must determine whether she stands for civilized or uncivilized warfare. We can no longer remain neutral spectators.”

Most Americans, however, do not yet share that sentiment. They want Wilson to express the moral indignation of the people, but still, at this moment of crisis, they do not want to risk involvement. “We must protect our citizens,” writes one leading newspaper editor, “but we must find some other way than war.”

Initially Wilson seeks seclusion. He needs time to work out what he feels and believes. For three days, he says nothing and stays out of the public eye.

“The news was almost more than Wilson could bear,” writes historian Link. “Before the Secret Service men knew what he was doing, he walked quietly out the main door of the White House.”

“For the President of the United States, this was by far the severest testing that he had ever known.”

One voice that favors US involvement in the war is former president Teddy Roosevelt.

“Roosevelt poured scorn,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “on those who argued that the United States must act as a neutral mediator.”

That role, the former president argues, could only be achieved not “by sitting idle, uttering cheap platitudes…while they [the Europeans] have poured out their blood like water in support of the ideals in which, with all their hearts and souls, they believe.”

As if on cue, in these days a century ago, French and Canadian troops launch an attack on German positions on the Western Front at Vimy Ridge in northern France, and the British attack to capture the Aubers Ridge, also in northern France.

Both attacks are unsuccessful, again with terrible losses on the Allied side. According to a German regimental diary of the attack, after the smoke of the artillery barrage lifted, “There could never before in war have been a more perfect target than this solid wall of khaki men, British and Indian side by side. There was only one possible order to give – Fire until the barrels burst.”