Allies Stopped Amid Confusion, Missed Opportunities.

Leader of Turks Emerges, Rallies Stiff Turkish Resistance

Special to The Great War Project

(7-10 August) The battle for Gallipoli in northwestern territory is intensifying during these days a century ago. Both the British and Allied attackers and the Turkish defenders battle fiercely, understanding that this is a pivotal moment in the war.

“The British and the Ottomans fought pitched battles all day on 9 and 10 August,” writes historian Eugene Rogan, “each side suffering heavy casualties. At one point on 9 August, the artillery was so intense that the brush caught fire and, whipped to high temperatures by the winds, burned British and Turkish wounded alive while their comrades were unable to reach them.”

The Turks still hold the advantage. They control the heights of the rocky hills of the Gallipoli peninsula.

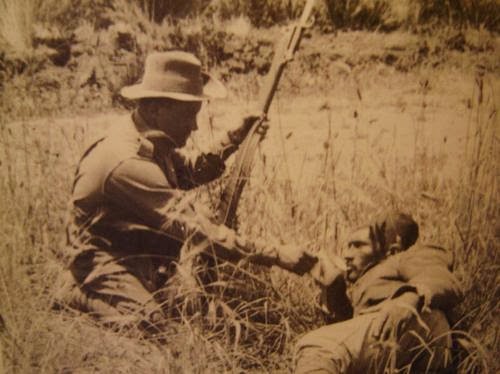

There is great confusion among the British, Australian, and New Zealand attacking force. In one instance, a small group of British and Gurkha troops reach the crest of one ridge, reports historian Martin Gilbert, “repelling a Turkish counter-attack with a bayonet charge.”

“They were about to drive the Turks back down the far slope when British naval gunners, not knowing that the summit was in Allied hands, opened fire, blasting the attackers and forcing them back.”

At this point, a key Turkish officer emerges at a place called Chunuk Bair to take his dramatic place in the history of Turkey.

His name is Mustafa Kemal.

At Chunuk Bair, the Turkish forces attack New Zealand troops who hold the heights there.

The Turks, under Mustafa Kemal’s command, attack the New Zealanders, but there is confusion among the Turkish troops.

“Kemal’s staff advised withdrawing down the eastern slope,” writes Gilbert, “but Kemal…urges his men to defend their native land.”

“Don’t rush it my sons,” he tells his troops as he walks along the Turkish trenches. “Don’t be in a hurry. We will choose exactly the right minute. Then I shall go out in front. When you see me raise my hand, look to it that you have your bayonets sharp and fixed and come out after me.”

Facing the Turks at Chunuk Bair are two battalions of fresh Allied troops who have not seen action.

Early on the morning of August 10, Kemal gives the signal.

One Allied battalion, the Loyal North Lancashires “were bayoneted to a man.” Another, the Wiltshires “were at that moment resting in a valley just below, have put down their rifles and equipment, could only turn and run.”

Mustafa Kemal, will survive the war and later lead his troops and his people to create the modern state of Turkey. He will be called Ataturk.

Still at Chunuk Bair, the Allied troops fight on. New Zealand machine-gunners cut down one flank of the Turkish advance. At another point on the line, the fighting is ferocious hand-to-hand combat.

“After more than half of the British troops had been killed or wounded, the survivors fell back,” reports Gilbert. Citing the battle’s official British historian, Gilbert writes: “The Turks, too exhausted to follow, and too weak even to stay where they were, had retreated to the main ridge…..the plateau [known as The Farm] forsaken by both sides, was held by the dying and the dead.”

“The Turks,” observes Gilbert, “remained in possession of Chunuk Bair.”

But for a few moments, the Allied troops who reach the top “had seen the waters of the Narrows [the ultimate goal of the Allied attack on Gallipoli] glinting far below.

“They were never to see them again. The British objectives of August 6 were never gained.”

Elsewhere on Gallipoli, at Suvla Bay, the site of an Allied landing, there is equal confusion. Initial British successes collapse and the Turks drive off Allied forces.

“After four days of fighting around the peak of Chunuk Bair,” writes historian Eugene Rogan, “the British withdrew to their original lines…They had no further reserves to keep up the fight.”

“The Allies suffer a total of 25,000 casualties in just four days.”

Gallipoli, observed historian Adam Hochschild, is a place where “the Turks were not playing their expected role as Orientals who could be conquered with ease.”

“They had German arms, good discipline, and fine generalship. Many of the Allied soldiers killed by Turkish machine guns never made it out of the small craft landing on Gallipoli’s beaches; they were packed into the boats so tightly that they remained sitting up even after being shot dead.

“The troops who did manage to come ashore never managed to advance more than five miles in from the coast.”

The number of dead and wounded at Gallipoli just keeps mounting – into the hundreds of thousands – on both sides.

I am currently a visiting research fellow at the Nanzan University Institute for Social Ethics in Nagoya, Japan. I have a particular intierest in historical memory, in other words how people interpret their own history. There is much done today on dialogue between religions and cultures, but I believe that if we really want to address the issues that separate people, dialogue on historical memory is essential. I am hoping that you webpage will be a help. I am Australian, so the Gallipoli campaign i s very important to me.

Michael, thank you very much for your comments. I am very much in agreement that dialog about historical memory is an essential step toward reconciliation of conflicts that go back a century or more. It’s one way of looking at the history of the First World War.

I hope you will continue to read my blog. Don’t hesitate to post additional comments, and if there is a way that my work can fit into yours, please let me know.

Best,

Mike Shuster