Ottoman Force Inflicting Heavy Losses; Food Supplies Dwindling.

‘As Near as Hell As We Are Likely To See.’

Special to The Great War Project

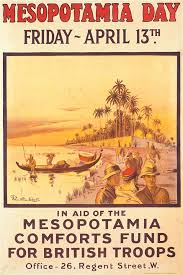

(18-21 January) The siege of Kut on the Tigris River in Mesopotamia [Iraq] grinds on.

“The British were fighting a steady and harsh battle against the Turks,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “seeking to reach the besieged garrison at Kut.” It’s a sideshow war that goes unnoticed in Europe “amid the more accessible war news of the Western Front.”

“The relief force Kut so desperately waited for was fighting its way, encountering continual Turkish resistance,” reports Gilbert. At the desert town of Hanna on January 27th one hundred years ago, the British reinforcement column again clashes with Turkish forces, suffering significant losses.

The British deploy forty-six guns against the attacking Turks, but they are wholly inadequate “to dislodge or demoralize the Turkish defenders before the assault.”

On the British hospital ship in the Tigris near the battle, one officer is reported to remark…

“this is as near hell as we are likely to see.”

Answered a wounded sergeant “I should say it is sir.”

The goal of the Battle of Hanna is to relieve the besieged British force at Kut. “In Kut itself,” reports Gilbert, “in contrast to the terrible heat of summer, sleet and an icy wind worsened the plight and morale of the attackers, and of the many wounded for whom no medical help was likely available.”

Reports one historian of the battle, “Lying in ankle-deep pools amidst a sea of mud, they must have plumbed the depths of agony; in any history of sufferings endured by the British Army the collective misery of that night of 21st January 1916 is probably without parallel” in nearly a century.

“A black-letter day for Kut in general, and me in particular,” writes one diarist at the battle. “About 6 a.m. in the pitch dark, the water burst into our front line…and flooded the trenches up to one’s neck. All the careful and dogged efforts of our sappers could not stop it.”

The Turks are also flooded out of their defenses and have to withdraw, running.

“We shelled his ragged masses with great glee.”

The British general in command of the reinforcement column begins to have fears that his force will not reach Kut. In a telegram to his commanding general, he writes, “I am very doubtful of morale of a good many of the Indian troops (it is a combined British and Indian force), especially as I have the gravest suspicions of extent of self-mutilation among them.”

Now he concludes he cannot break through to Kut. He is dismissive of the capabilities of his Indian troops. “One or two all-British divisions are all we want. There now is time to demand good white troops from overseas, and Army Corps to save and hold Mesopotamia if the Government considers it worth holding.”

Despite his doubts, the British general in command of the reinforcement column orders his troops “into a frontal assault across open ground on well-entrenched Ottoman positions,” according to historian Eugene Rogan. “The attackers slipped and stumbled in the slick of mud left by days of heavy rain, facing intense gunfire without so much as a shrub for cover.”

British casualties are high. “After two days of battle,” reports Rogan, “they had no choice but to give up and retreat.”

Meanwhile inside Kut, conditions are swiftly deteriorating. Food supplies are dwindling, presenting General Charles Townshed, in command of Kut, with some hard choices.

“Townshend’s first priority was to reduce his forces’ consumption,” reports Rogan.

He orders all rations cut in half. This applies to both the military and civilian populations of Kut. “He then ordered British troops to conduct a house-by-house search to requisition food stores.” The order outrages the civilians in Kut.

Townshend also issues orders to commandeer shops, kick in the walls of houses, and strip houses of their woodwork for heating fuel.

So far the siege has lasted about a month. General Townshend is preparing the town for at least another two months.

And that may not be enough.