Wilson Struggles to Treat Britain and Germany Equally;

Americans In Anti-War Mood

Special to The Great War Project

(22-25 January) By the beginning of 1916, the American president Woodrow Wilson still is struggling with his stance of neutrality.

Wilson is trying to formulate a policy that will address the potential hostile acts at sea of both Germany and Britain.

The year 1915 has been a difficult one for Wilson and his advisers. After a long series of hard negotiations, the U.S. forces Germany to limit its declared policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against all American shipping, whether carrying munitions or not.

At the same time Britain insists it has the right to intercept American shipping on the high seas if it believes American ships are carrying contraband, even food, and thus are breaking the British embargo of Germany.

By the beginning of 1916, writes historian and Wilson biographer Arthur Link, “Wilson had accepted the legitimate exercise of British sea power in the suppression of American trade with the Central Powers [Germany and Austria-Hungary].”

Germany does not see Wilson’s policy as truly neutral.

Throughout 1915, Berlin has been waging a covert war in the United States. It involves espionage and sabotage of American weapons shipments in the U.S. bound for Britain.

“At the same time,” writes Link, “by public statements and diplomatic correspondence, [Wilson] had led the American people to understand why their government could pursue no other course within the framework of neutrality.”

It has been troubling for Wilson to establish these policies with both Britain and Germany. “The two decisive questions affecting America’s economic relations overseas – the export of contraband and private loans and credits to belligerent governments [including Britain]…

…Wilson had taken a solidly neutral position that gave no undue advantage to either side.”

At least that is what Wilson and his Secretary of State Robert Lansing believed.

Link concludes, “By the end of the first fourteen months of the war, no partisan of either alliance could fairly say that the policies of the United States were unneutral. No belligerent government could fairly complain that the hand of the Washington administration was raised against it.”

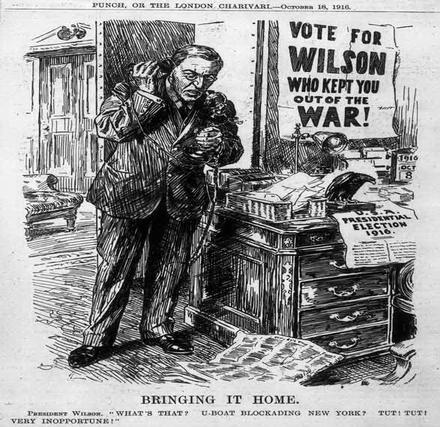

The mood in the country at this moment in the war a century ago, is strongly anti-war. The American public does not want to get into this fight.

It’s a narrow line the president must walk.

After months of heated debate across the country and inside his White House, Wilson is successful in gaining the support of the majority of Americans for his policy.

“To say that these were all substantial achievements is not to imply that they were necessarily wise or right,” observes Link. “It is to say only that Wilson and his advisers on the whole accomplished what they set out to do, and that they served the national will by doing so.

“Whether they were also promoting the national interest and serving the peace of the world, only time would tell.”

These issues will soon confront Wilson head-on. This year, 1916, is an election year. Wilson intends to run for re-election on the slogan: He kept us out of war.