Food Stores at Kut All But Gone; A Bribe for the Bey.

In Contested Waters, Return of the U-Boats

Special to The Great War Project

(21-25 March) On this day a century ago, the British introduce a new weapon into the war at sea — the depth charge.

A British ship drops an underwater explosive in the waters near Ireland and destroys a German submarine.

Depth charges on the stern of allied ship, date and place uncertain.

Still, writes historian Martin Gilbert, “the balance of naval sinking lay with Germany. On March 22nd one hundred years ago, a German U-boat torpedoes and sinks a British ferry carrying civilians between Britain and the Netherlands.

The Germans believe the ferry is carrying soldiers. It is not. More than fifty passengers drown including three Americans.

The Germans have good reason to believe the ferry could be carrying soldiers. According to Gilbert, “An American appeal to the allies, sent two months earlier not to arm merchant ships or passenger liners was rejected by Britain and France that same day, March 23.”

The war at sea is widening on both sides. In Berlin, the German parliament is about to vote for immediate unrestricted submarine warfare. A German submarine sinks a Russian hospital ship in the Black Sea. Reports Gilbert, 115 patients, nurses, and crew were drowned.

At the same time, in the Middle East, the British position at Kut, on the Tigris River, is now untenable.

More than 8,000 British and colonial Indian troops are under siege for some three months, and their food and supplies are running out. Halil Bey, the commander leading the Ottoman siege, invites the British commander to surrender.

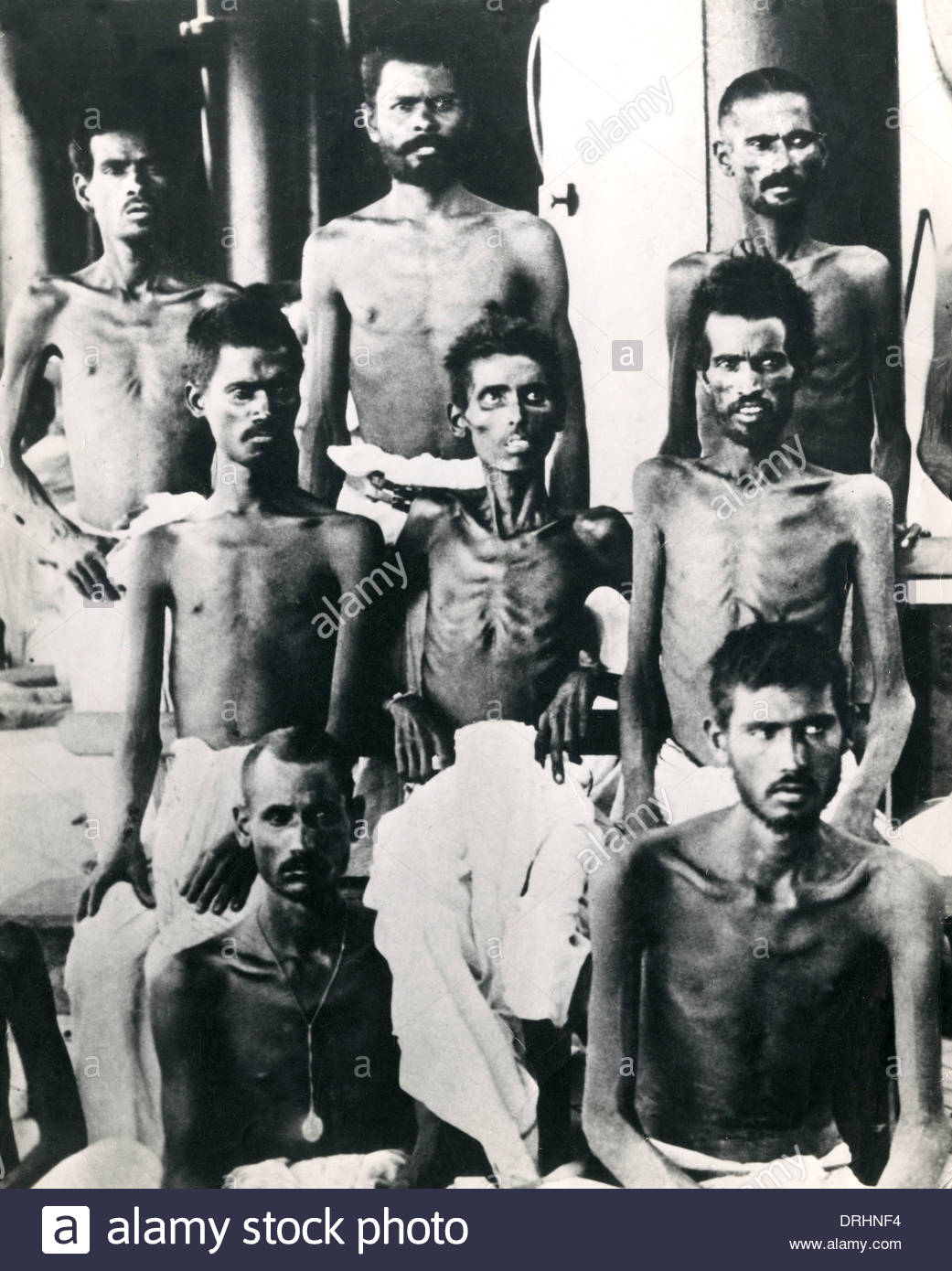

Starving Indian soldiers at siege of Kut, 1916.

“You have heroically fulfilled your military duty,” the Ottoman general writes. “From henceforth there is no likelihood that you will be relieved. According to your deserters, I believe that you are without food and that diseases are prevalent among your troops. You are free to continue your resistance at Kut, or to surrender to my forces, which are growing larger and larger.”

The British commander at Kut declines the offer. At the same time, he calculates that his food supplies will run out on April 17th.

The British position in the east is nothing less than disastrous. It comes only a few months after the humiliating British withdrawal from the Gallipoli Peninsula in western Turkey. Now, writes historian Eugene Rogan, “the British faced catastrophic defeat in (Mesopotamia) Iraq.”

The British war cabinet meets in London to assess their now untenable position in the Muslim world. “The British government,” reports Rogan, “feared that Ottoman victories risked provoking pan-Islamic revolts in India and the Arab world.”

Reports Rogan, “In their bid to forestall disaster, the British cabinet was willing to consider even the most unrealistic of schemes” that sound familiar now a century later.

One is to…

…spark mass uprisings in Iraq – especially in the Shi-ite cities of Najaf and Karbala, using provocateurs to infiltrate behind the Ottoman lines.

The aim: draw Ottoman troops away from Kut, thereby relieving the pressure on the desperate British force there.

Another proposal is even cruder, in Rogan’s view.

“Convinced of the inherent corruption of Turkish officialdom,” Rogan writes, the British could offer “a massive bribe to a senior Ottoman commander to turn a blind eye” to the British withdrawal from Kut with all his forces.”

The British begin implementation of both plans.

Lawrence in Arabia, third from right.

They tap a low-ranking intelligence officer, based in Cairo — Captain T.E. Lawrence.

Lawrence appears ideal. He speaks Arabic. He has held extensive conversations with Arab officers who are prisoners-of-war in Egypt.

Most important, Lawrence “has the self-confidence to believe he could succeed in such an improbable mission.”

Lawrence leaves Cairo bound for Basra on March 22nd.

His voyage sets in motion a series of events that will reverberate across the Middle East, and that are still unresolved today, a century later.

And Lawrence will forever become known as the legendary “Lawrence of Arabia.”