President Wilson Seeks Neutrality; Some Call It Non-Neutral

Democrats Nominate Wilson for Second Term

Special to The Great War Project.

(6-8 July) The bloodletting at Verdun and on the Somme strengthens the forces in the United States – including President Woodrow Wilson – who feel the United States must stay out of the war.

“For most Americans,” writes historian Matthew Davenport, “the bloodshed and thunder of the first two and a half years of the Great War was no more than a distant noise.”

Support Wilson button, 1916.

“Only tragedies that touched home – the death of 128 Americans aboard the Lusitania and injuries to two dozen more aboard the Sussex when each was torpedoed by German U-boats – raised voices of outrage.”

“But still few desired war.”

“This lack of belligerence was not surprising,” writes Wilson’s biographer John Milton Cooper. “Newspaper and magazine coverage of the carnage on the Western Front and the recent use of poison gas left no room for illusions about the horrors of this war.”

The details left few Americans clamoring for war.

Nine months of fighting a century ago at Verdun, “had cost the French Army more casualties than either side in fighting the entire American Civil War.”

News reports of these enormous incomprehensible losses convince most Americans to stay away.

That is certainly the view of President Wilson mid-June, 1916, a century ago. Reports Davenport, “Wilson stressed that the United States must be neutral in fact as well as in name during these times that are to try men’s souls.”

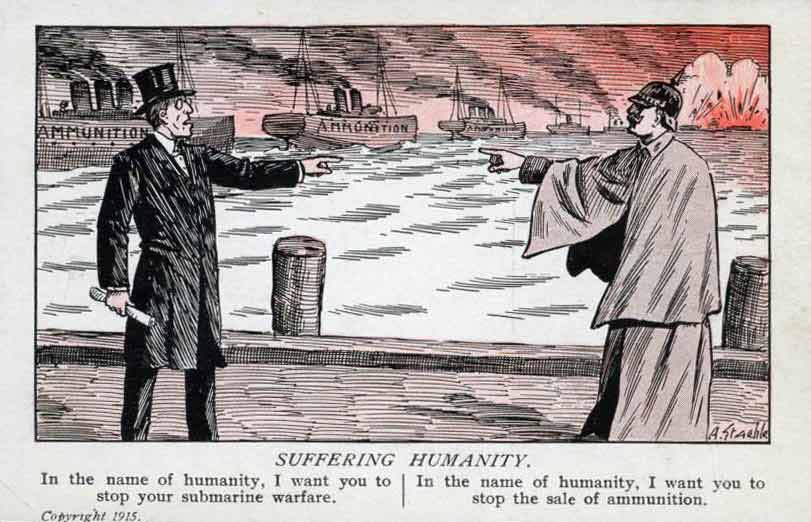

Why this demand? Because many see Wilson’s policy toward the war as non-neutral neutrality.

Non-neutral neutrality? What does that amount to?

Wilson maintains that his policy of neutrality permits the U.S. to lend Great Britain enormous amounts of money to keep it and France from going bankrupt and losing the war.

And make no mistake, the Allies are on the brink of bankruptcy and a collapse of their war efforts.

Wilson insists his notion of neutrality permits loans and weapons sales to all belligerents, including Germany. But Britain’s very effective blockade makes such contributions with the German war effort all but impossible.

Uneasy US relationship with Imperial Germany.

This provokes Germany to threaten submarine attacks on British and American ships that might be carrying weapons and other contraband to Great Britain.

“It was hardly surprising,” writes historian Thomas Fleming, “in light of what was transpiring in the United States, that the leaders of Germany looked with growing skepticism on Wilson’s claim to be an unbiased peacemaker who could mediate a settlement between the warring nations.”

Another issue that emerges in the U.S. is the debate about military readiness, the call for the U.S. to expand its military to be ready for any contingency. At this stage in its history, the United States maintains only a small military.

At first, Wilson resists building up the American army. He urges Americans to “put a curb on our sentiments.” But in these days a century ago, he succumbs to political forces that advocate better preparedness.

“The need for some level of increased readiness,” reports Davenport, “was a growing national attitude, and many wealthy, influential business leaders set up and funded military training camps.”

The goal: “to train and prepare a large class of citizen reservists in case of war.”

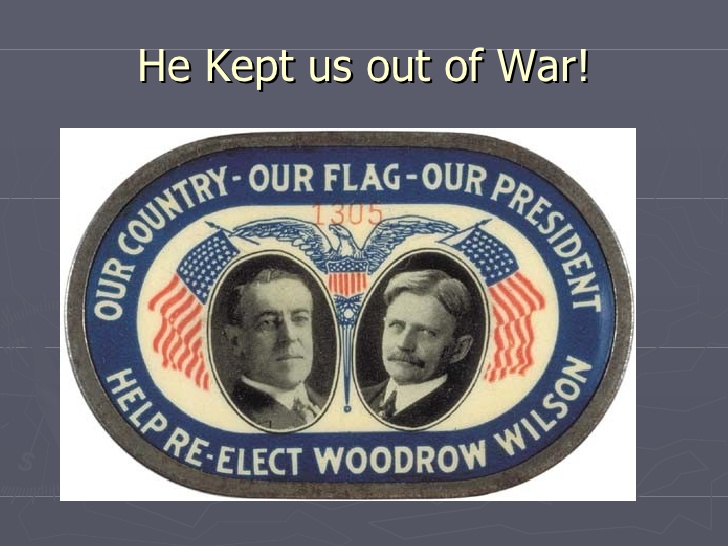

In mid-June, a century ago, the Democrats hold their presidential convention in St. Louis.

Re-elect Wilson, 1916.

They choose Wilson to run for reelection as their standard bearer in the 1916 presidential election campaign. He bases his reelection campaign on the slogan, “He kept us out of the war.”