The Ugly Aftermath of Battle, for Victor and Vanquished Alike.

“German, Austrian, Russian, Lay There at Peace, in a ‘Brothers’ Grave.”

Special to The Great War Project.

(13-16 July) The murderous fighting at the Somme continues, bringing with it the randomness of death.

Many soldiers write home with tragic stories about the randomness of death.

The dead at the Somme, summer 1916

One British soldier writes. “Our sergeant had just given us our rum ration and gone to the shell hole where the gun team were, and..

…here unfortunately one gas shell found its mark, landing in the center of the gunners. Poor lads, it wiped the whole of them out.”

Soldiers on both sides send home hundreds of thousands of letters from all fronts of the war. “Often,” reports historian Martin Gilbert, “they are letters that describe to a wife or a parent the fate of his or her loved one.”

Wounded British soldiers at the Somme, summer 1916.

They are terribly painful.

“About halfway across No-Man’s Land,” writes one British soldier, “whilst waiting in a shell-hole for one of our own barrages to lift, I became aware of the fact that Joe was in the next hole to mine, and we smiled encouragement to each other.”

“Enemy machine guns were sweeping the whole place with explosive bullets, and there was a fearful noise, and speech was impossible.”

“The streams of death whistled over our shell-holes coming from the left flank, and Joe’s hole being to the left of mine, he received the bullet in his side.

He slipped away quietly – just a yearning glance, a feeble clutching at space, and then a gentle sinking into oblivion, with his head on his arm.”

Private Joseph Bailey, killed at the Somme, 1916.

On the Eastern Front, conditions there are equally dreadful.

The Russians are on the offensive in eastern Europe, pushing the German and Austrian forces westward. In early July, a century ago, the Russians take more than 30,000 German prisoners.

The British nurse Florence Farmborough is witness “to the ugly aftermath of the battle, for victor and vanquished alike.”

“As the fighting became more intense,” she writes, “the wounded lay massed outside our temporary dressing station, waiting for attention – countless stretcher cases among them. A few would crawl inside, beseeching the care they so urgently needed….in the evening the dead would be collected and placed side-by-side in the pit-like graves dug for them on the battlefield.”

“German, Austrian, Russian, they lay there at peace, in a ‘brothers’ grave.”

The Russian advance is relentless. They push the Austrians back into the Carpathian Mountains. Among the Austrian soldiers trying to prevent the Russian advance further — the young Ludwig Wittgenstein, later to become a world famous philosopher.

Russian priest prays for the wounded, Russian Front, date and place uncertain.

He writes in his diary for July 15th a century ago, “In the mountains, bad, quite inadequate shelter, icy cold, rain and mist. An excruciating life.”

Nurse Farmborough adds, “The mud is so thick that high boots get sucked off the owners’ legs.”

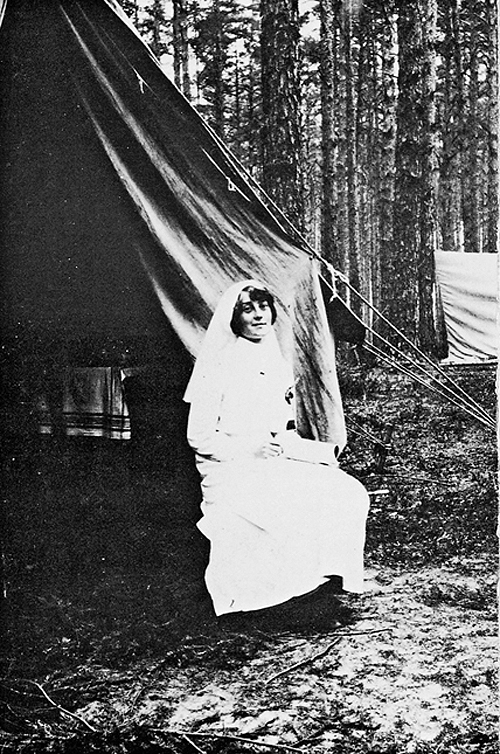

British nurse Florence Farmborough.

Several nurses are killed in the shelling. Farmborough’s dressing station receives 800 wounded men in 24 hours.

She relates the story of a young Tatar soldier fighting in the Russian army. He is carried to the operating table. He could speak no Russian, she writes, so we brought in a Tatar driver who understood his language. But it is too late. “He’s gone,” said a voice.

The Russians also experience heavy losses. “Stomach wounds were in the majority. Amputations were also common,” reports Gilbert.

The scene is ghastly. According to Farmborough, “One leg was so heavy I could not lift it from the table.” Someone helps her carry the leg to the tiny shed where a stack of amputated limbs is awaiting burial.”

“I had not been in that shed before, and I turned away hastily.”

She drinks some water and soon the choking feeling subsides and “I was myself again.” But she can’t help but ponder and fear the randomness of death in this war.

It is difficult for me to see this loss of life at the Somme and the incompetence of the British military leadership.

Such a waste of young men’s lives!

horror made human.thank you, mike. alex