His Last Day on the Battlefield

A Sense of Something Poetic, Now Gone

Special to The Great War Project

(12-15 August) The Battle of the Somme shows no signs of ending, even though it’s now more than six weeks old.

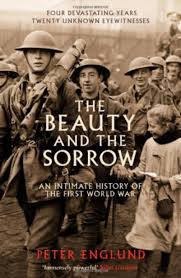

What’s it like? What is it really like to live through this horror? There are several ways to see. Swedish historian Peter Englund puts together what he calls “The Beauty and the Sorrow, An Intimate History of the First World War.”

It’s a kind of oral history, and one of the voices is Kresten Andresen, a Danish soldier fighting on the German side on the Western Front. He is “one of the soldiers,” writes Englund, “who will have to face the [British] attack.”

German prisoners of war marched by wounded British troops, the Somme August 1916

“His regiment has been sent in to reinforce one of the most exposed sectors on the Somme.”

Englund describes the scene. “No more sun, just mist and haze. The front line has not moved much since the middle of July but the battles continue to rage. The landscape is strangely colorless. All the colors, particularly the greens, are long gone.

The storm of shells having kneaded everything to the same drab grey-brown shade.”

The British Commander Field Marshall Douglas Haig seeks to launch an attack – even a small one – for the benefit of a royal visit. King George V is visiting the troops and, reports Englund, Haig would like to “welcome His Majesty with some small victory.”

King George V observes fighting at the Somme, date uncertain.

“One of the German soldiers who will have to face that attack is Kresten Andresen.”

At this point in time, a century ago, Andresen, 23 years old, writes to his parents. “I hope I have now done my bit here, for the present anyway. One can never know what will happen in the future. But even if we are sent somewhere in the very depth of the sea, we could not go anywhere worse than this place.”

Andresen’s company is devastated by ceaseless shell fire. Most of his comrades are dead.

And still the shells rain down.

“It’s like meeting “a monster from the sagas,” he writes.

In a letter home, Andresen writes “At the beginning of the war, in spite of all the terrible things, there was a sense of something poetic. That has now gone.”

Andresen finds himself on the front line. He is still alive, reports Englund.

The Beauty and the Sorrow, voices from the Somme, 1916.

But the battle field is pure chaos. British artillery fire is relentless, but it fails to coordinate with the movement of British infantry, as it is supposed to do.

“Soon,” reports historian Englund, “the barrage disappears into the distance, leaving the lines of advancing British infantrymen behind, (and exposed). And then these lines run straight into the German curtain of fire, and even into each other.”

“In all the smoke and confusion two British battalions end up fighting one another. The men who manage to push forward in spite of this soon come under cross-fire from German machine-guns hidden in a sunken road.”

“Kresten Andresen is still alive around the middle of the day on August 8th” a century ago.

Later in the afternoon, the German units manage to mount a counter-attack. They re-capture stretches of trenches they lost earlier in the day, and they overcome the British attackers.

In one trench they find one of their own, wounded, hiding in a bunker. He has heard, Englund writes “that the British bayoneted the wounded to death,” even though he witnesses the British taking prisoners and marching them to the rear, away from the fighting.

Massive unexploded German shell, the Somme August 1916.

Soon it is determined that in his company “there are twenty-nine men that cannot be accounted for among either the living or the dead…

Kresten Andresen is one of them.

“His fate is unknown.”