British Frustrated by Arab Inaction;

The Arrival of a Legend-To-Be.

Special to The Great War Project

(8-11 October) By this time a century ago, the Arab Revolt in the Middle East — in the territories under the control of Hussein, the Sherif of Mecca — is four months old. For the Arabs and their British supporters, things are not going well.

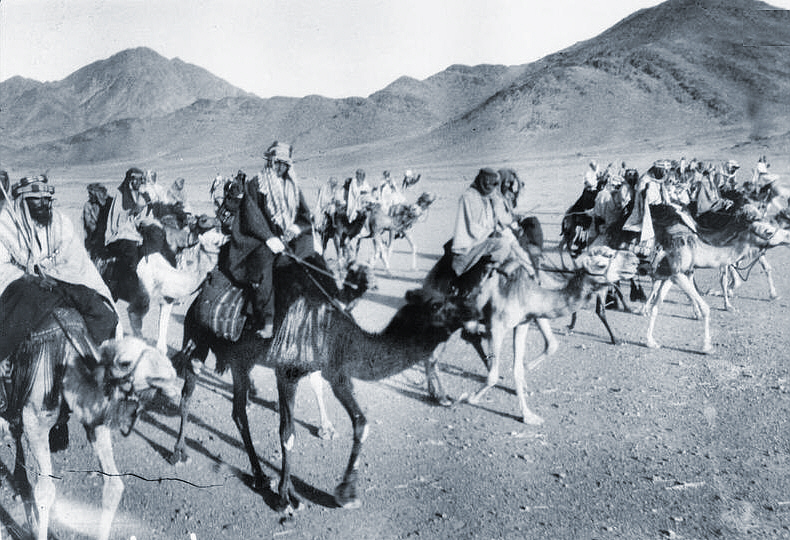

Arab troops in the Arab Revolt, date uncertain.

“By October 1916,” writes historian Scott Anderson, “the Arab Revolt was fast reaching a crisis point.”

“The British had been funneling gold and rifles to Hussein for many months now,” Anderson observes. “They have been hearing the grand plans of the Arabs but “unblemished by any attempt at actual execution.”

Finally, the British inform Hussein there will be no more funds until the revolt actually begins in earnest.

The Arabs quickly seize Mecca, “overpowering the tiny Turkish force there,” reports Anderson. The Arabs also get help from a British naval bombardment attacking the city of Jeddah on the Red Sea coast.

But elsewhere the Arabs do not fare so well. In Medina, the largest city in the Arab peninsula, the Arabs face “a vastly larger and entrenched Turkish garrison, some ten-thousand soldiers.” Initially the Arab attackers are slaughtered by machine-gun and artillery fire.

Arab troops of the Arab Revolt.

“A month into the revolt,” writes Anderson, “an uneasy stasis had set in.” The Arabs hold Mecca and Jeddah, the Turks Medina.

But as the summer of 1916 wears on into the fall, “with the rebels’ disorganization becoming more apparent and the signs of a Turkish counter-offensive were imminent, the debate over the Arab Revolt among the British generals in Cairo and London takes on an added urgency.”

British troops are not a part of this campaign however, except for a small British contingent on the Red Sea coast. Anderson writes: “To allow the British to venture farther inland let alone to bring in whole units of rescuing British Christian soldiers in the event of a major rebel setback would be to play directly into the hands of Turkish propagandists and risk the immolation of all concerned.”

“Hussein might be regarded as a traitor not only to the Ottoman Empire but to Islam as well.”

It could mean, Anderson reports, “Britain’s imperialist, Crusader intentions laid bare before an enraged Muslim world.”

Into the fall, the British and the Arabs continue to squabble over the terms of full scale cooperation.

Finally, by October a century ago, “The time for such dithering had come to an end,”

Anderson writes. “The Turkish garrison in Medina was now stronger than at the revolt’s outset, having been reinforced by rail. It had recently pummeled a rebel attack force.”

This changes the terms of cooperation between the Arabs and the British. Hussein is finally persuaded to allow a significant contingent of British troops into the Arabian peninsula.

At this moment in the war, several British officers arrive in Jeddah to help steer the revolt. Among them is Captain T.E. Lawrence, soon to acquire legendary status as Lawrence of Arabia.

Capt. T.E. Lawrence (left), in Arabia, date uncertain.

Lawrence arrives in Jeddah for the first time by ship, and his arrival strikes him powerfully. Shortly after dawn, in the early morning light, “Lawrence observed only light and shadow among the buildings of the town, while beyond, he writes later, “it was the dazzle of league after league of featureless sand.”

“As the steamer approached its berth,” writes Anderson, “he was to experience that phenomenon common to most who approach Arabia from the water, that moment when the sea-cooled air abruptly collides with that blowing off the land.”

As Lawrence would write, “it was at that instant when the heat of Arabia came out like a drawn sword and struck us speechless.”