Russia In Turmoil; Alarm in Paris and London.

Special to The Great War Project

(8-12 February) The Germans are now preparing “to face the might of the United States,” writes historian Martin Gilbert.

But at the same time, their defensive actions on the Western Front – where the German war effort is potentially at serious risk – “was offset by…

…the continual news from Russia of military weakness and anti-war feeling” in the East.

Anti-war sentiment is growing, especially in Russia.

One top German commander writes in his diary a century ago, ‘it would seem that [Russia] cannot hold out longer than the autumn,” writes Gilbert.

At this moment, hundreds of Russians are protesting the war in the streets of Petrograd. The British military observers with the Russian army report to London that as many as three million Russian soldiers have been killed.

“Recriminations among the Allies,” writes historian David Stone, “were especially bitter” in these days a century ago. The British and French want a Russian commitment to an early offensive on the Russian Front.

But the Russians keep putting off the planning.

There was “understandable alarm in Paris and London,” reports historian Stone, “which feared war weariness in Russia – understandably.”

The British observers report that Russia may not be able to field enough fresh troops to face expected military losses in 1917.

“There was little common ground,” reported Stone, “on which the two [Allies] could agree.”

Anti-war protest in Russia, 1917.

Relations between the Allies and Russia are rapidly deteriorating.

Nevertheless, the Russian Tsar still has dreams of expanding the Russian Empire to annex Constantinople and the nearby waterway Straits, still under the control of the Ottoman Turks.

All the Allies are still maneuvering to acquire territories of their adversaries. In mid-February a century ago, secret agreements are still on the table.

“On February 12th,” writes historian Gilbert, “the Russian government sought a further secret assurance with regard to its western frontier. It proposed doing so by giving France a free hand with regard to the German frontier.”

At this moment a century ago, the Russians and the French are in agreement about territories they will occupy when the war ends. Gilbert writes: “On that day the Russian Government accepted, in strictest secrecy, that Alsace-Lorraine [occupied by Germany since 1871] would be restored to France.”

This secret agreement also gives to France alone the power to determine the border with Germany after the war. And that includes the coal district of the Saar, long considered German territory.

German prisoners of war in Russia.

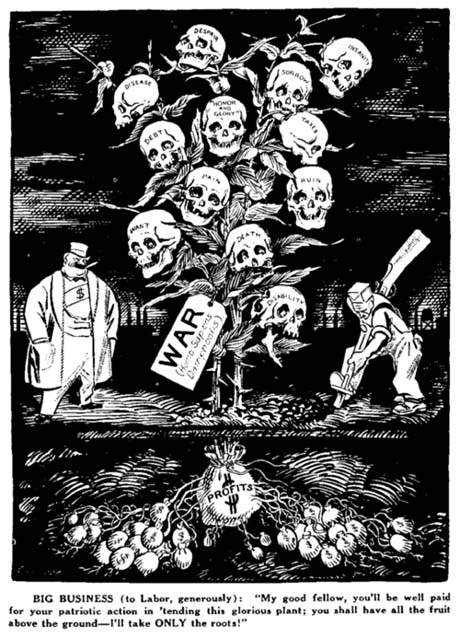

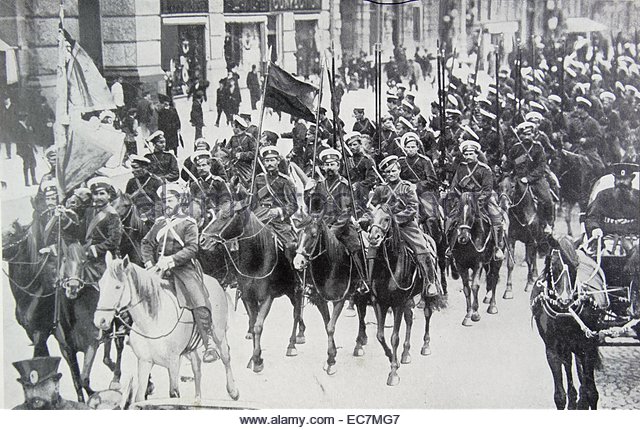

Overlooked in all this secret maneuvering, according to Gilbert, “it was becoming almost impossible for many Russian officers to maintain military discipline.” In one notable case, Russian cavalry men are issued live ammunition and order to break up an anti-war demonstration.

Instead effectively the cavalry squadron addresses the demonstrators, many soldiers among them.

“The Russian people,” one soldier on horseback hollers, “wanted an end to the slaughter of an imperialist war; they wanted piece, land, and liberty.”

The speaker also called for an end to the Russian monarchy.

And then the soldiers, cavalry men, and civilians intermingled together.

Throughout the Eastern Front,” writes Gilbert, “the Bolsheviks were appealing to the soldiers not to fight and to join soldiers’ committees to uphold and propagate revolutionary demands.

Russian cavalry.

“The United States was not yet in the war,” reports Gilbert, “and Russia was in turmoil.”

It is a serious, growing crisis for the Allies.

They agree on a general offensive for April 1917, a century ago.