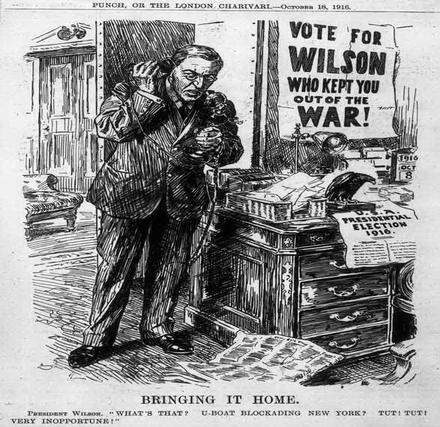

Wilson to Congress: I Am a Man of Peace,

But U.S. Must Arm American Ships.

The Slow, Slow Creep to War.

Special to The Great War Project

(26 February) With President Woodrow Wilson’s decision to break diplomatic relations with Germany a century ago, debate about possible American entry into the war heightens.

“Debate about the war did not cease of course,” writes historian Michael Kazin. “Lawmakers from both [American political parties] delivered passionate speeches for and against taking new and aggressive actions to punish Germany.”

The debate over American intervention.

“Interventionist newspapers like the New York Times,” reports Kazin, “predicted a swift economic decline if transatlantic shipping did not resume soon.”

The Germans had begun to attack U.S. merchant ships, and soon there are American casualties.

But still President Wilson is not prepared to declare war. “Unless the president changed his mind,” reports Kazin, “the anxious status quo might last – as the departing German ambassador hoped.”

(The German ambassador is preparing to leave the United States after the break in relations.)

But privately Wilson is moving closer to taking the U.S. into the war. Writes Kazin: “By mid-February Wilson had privately arrived at a decision he knew carried the risk of war.”

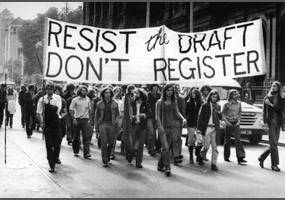

Opposition to war takes to the streets.

“The United States would place guns powerful enough to sink a submarine on merchant vessels bound for Europe. For the president, armed neutrality was a middle course – between letting the Germans have their way on the high seas and joining the Allies.”

And in addition, reports historian Kazin, “it would also, he hoped, appease shipping companies who were seeing their profits rotting away on domestic wharves. Before announcing it, Wilson told the members of his cabinet he wanted to seek the approval of Congress, although his advisors assured him he had the legal power to act without it.”

On February 26th, precisely a century ago, “Wilson unveiled the idea before a joint session of Congress.” Writes Kazin. “He shrewdly appealed both to national self-interest and to the strong desire of most Americans to avoid war.”

“He acknowledged that no U-boat had yet torpedoed an American ship of any size.”

Wilson tells Congress he is committed to maintaining his policy of neutrality. “I am anxious,” he declares, “that the people of the nations at war also should understand and not mistrust us.”

“I am the friend of peace,” Wilson says, “and mean to preserve it for America so long as I am able.”

Wilson tells Congress “even now he is not proposing or contemplating war or any steps that need lead to it,”

“In asking Congress to authorize funds for arming merchant ships, he referred vaguely,” observes Kazin, “to other instrumentalities or methods that might be needed to protect our ships and our people in their legitimate and peaceful pursuit on the seas.”

Kazin praises the president. “No previous speech Wilson had delivered about the Great War was greeted so favorably. And by such disparate voices.

Pro intervention, San Diego, 1917.

“Newspapers loyal to both parties and supporting either intervention or peace all praised his ‘wisdom, his logical and reasonable appeal, and his honor and courage.”

But a few voiced suspicions that some of the language in the speech might be a backhanded way of preparing the nation for a declaration of war.

Still, most in the United States believe that the speech is designed to maintain Wilson’s neutrality policy to keep the United States out of the war.

That photo of war protesters has got to be from the 1960s, not 50 years earlier.

Yes. Look at the clothing, hair styles, and the vehicle in the background.

Thanks for the correction. Good catch.