Turmoil Among the Allies

Who Will Fight the War Now?

Special to The Great War project.

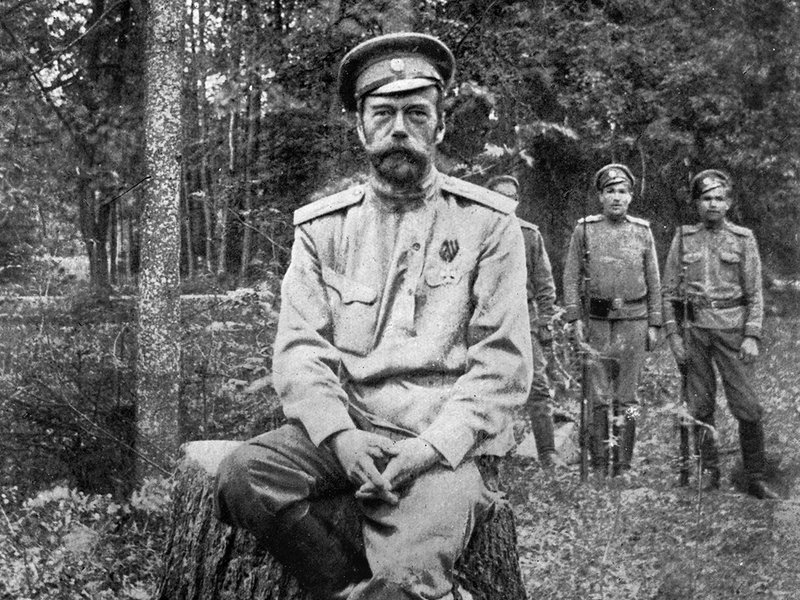

(13-18 March) On March15th a century ago, under intense pressure and with no possibility of retaining his crown, Tsar Nicholas the Second of Russia abdicates the throne.

He turns over the monarchy to his son. “I request all to serve him truly and faithfully,” Nicholas declares.

Tsar Nicholas abdicates the Russian throne.

“The war had claimed its first Allied sovereign,” writes historian Martin Gilbert. “The 300-year-old imperial system over which the Tsar had presided was over.”

Now what?

Will Russia remain with the Allies and continue the fight?

Writes one foreign diplomat in the Russian capital Petrograd,

“Russia is a big country, and can wage war and manage a revolution at the same time.”

Not quite.

On March 17th one hundred years ago, the commander-in-chief of the Russian navy is murdered — shot and killed. “The revolutionary forces were strong and unleashed,” writes Gilbert. “Anti-war fever was intense.”

The first Russian revolution

Nevertheless, the following day Russia’s Foreign Minister announces, “Russia would remain with her allies. She will fight by their side against a common enemy until the end, without cessation and without faltering.”

As the question of Russia’s continued commitment to fighting the war dominates the news from Russia, the news from the U.S. is equally urgent – will the United States enter the war?

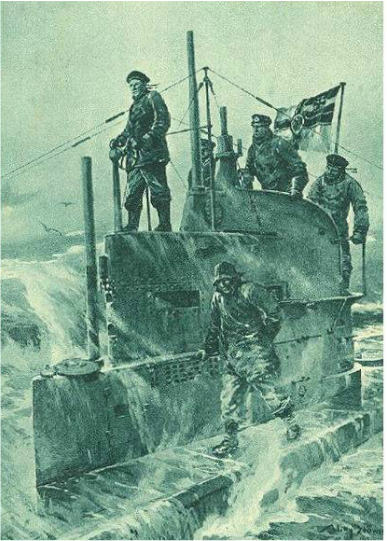

Just two weeks earlier, a merchant ship, the Laconia, is torpedoed and sunk off the coast of Ireland, on its way from New York to Liverpool. Seventy-three civilians are on board including six Americans. And a crew of more than two-hundred.

“An almost forgotten footnote,” writes historian Gary Mead, “the sinking of the Laconia was yet another provocation.”

The passengers in lifeboats are left to die. The submarine that sinks the ship makes no effort to save any of the passengers.

“The view of Germany by most Americans as utterly perfidious was now complete,” reports Mead.

The American president, Woodrow Wilson, formally enters his second term on March 4th, having been reelected the previous November.

Wilson is conscious, writes Mead, “that his policy of pursuing peace and neutrality upon which he had been re-elected was a complete failure. America was going to be dragged into this European conflagration, whether it wished for it or not.”

In his second inaugural address, Wilson calls for “an America united in feeling, in purpose, in its vision of duty, of opportunity, and of service.”

“That call would soon be put to the test,” observes historian Mead, “as a succession of American merchant ships were sunk by German U-boats.”

On March 12th without warning, the U.S. steamer Algonquin carrying mostly food is shelled and sunk by a German submarine — the American flag clearly painted on the ship’s side, reports Mead.

Depiction of the sinking of the Algonquin.

Then other American ships are attacked in quick succession: the Vigilancia out of New York sunk in seven minutes, the City of Memphis, the Illinois, shelled without warning, all within just a few days in mid-March a century ago.

“Even President Wilson’s patience had run out,” reports historian Mead. In a Cabinet meeting every one of [Wilson’s] ministers, including those who had previously been ardent supporters of a pacifist line, voted for war.”

“Now it would be peace through victory.”

Curiously, the sinking by a U-boat of a DIFFERENT ship also named “Laconia” twenty-five years later was a watershed event in WWII’s Battle of the Atlantic.