Pershing in London Tells King No Aircraft On the Way

Soldiers Lay Their Rifles Down

Special to The Great War Project.

(11 June) At this moment in the war, it is hard to resist the conclusion that in the war in Europe, there is no “winning side” – every side is losing the war.

“The war on the battlefield,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “had become one of bizarre contrast. On both the Eastern and Western Fronts the savagery of the conflict was matched by mass desertions, mutinies, and fraternization.”

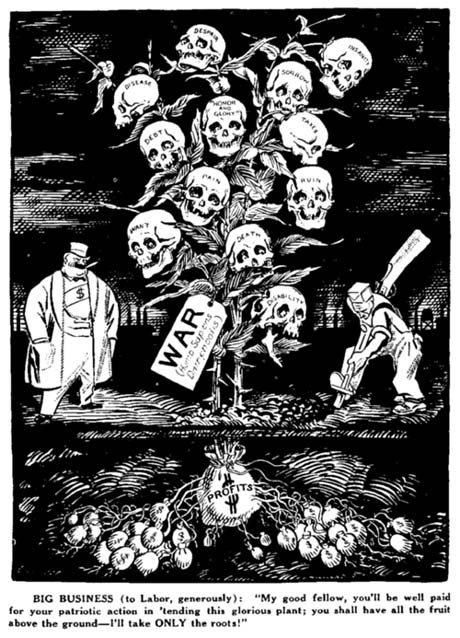

Antiwar leaflet

“On the Eastern Front,” one senior general writes in his diary, “an armistice was to all intents and purposes in being in many points. At other points there was fighting.”

Writes historian Gilbert, “Mutinous French troops everywhere revealed their hated of the war.” Most French divisions between the front line and Paris are unreliable.”

In Britain at his moment in the war, anti-war sentiment is spreading rapidly. One-thousand pacifists are in prison.

Declares philosopher and anti-war activist Bertrand Russell, “By their refusal of military service, conscientious objectors have shown that it was possible for the individual to stand against the whole power of the state.”

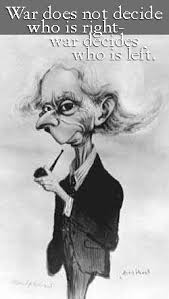

Caricature of British anti-war philosopher Bertrand Russell

Russell receives a huge standing ovation when he makes this declaration at an anti-war conference in the British city of Leeds, reports historian Adam Hochschild. “The control of events,” Russell writes, “is rapidly passing out of the hands of the militarist of all countries. A new spirit is abroad.”

Elsewhere, writes historian Gilbert, the mood is not so optimistic. “The will of governments to continue to fight, despite the actual horrors of trench warfare, despite the chaos in Russia, despite mutiny in France, did not dissolve.”

This is a crucial moment in the war – mid-June one hundred years ago — and no government is willing yet to declare opposition to the war.

In fact, the British government is hard at work planning a new offensive, despite a growing awareness in London that “the French were finding it difficult to go on, with their reserves physically and mentally exhausted.”

At this moment in June a century ago, as the British war cabinet in London is planning their next offensive, the leader of the American Expeditionary Force, General John J. Pershing and his staff, reach Liverpool.

Then the following day in London, Pershing meets with King George at Buckingham Palace. The king cites Britain’s terrible losses. Then he remarks that there are rumors the U.S. “would soon have 50,000 aircraft in the air.”

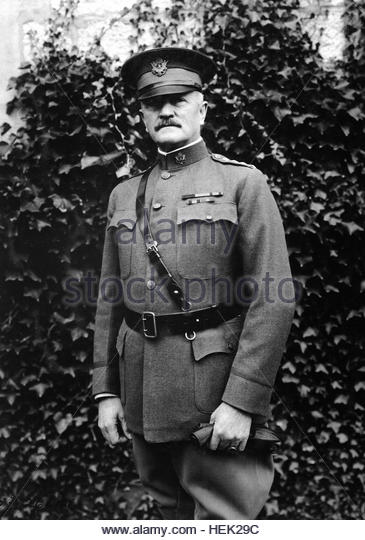

General John J. Pershing, commander of American Expeditionary Force.

According to Gilbert, Pershing is embarrassed to tell the king “such reports were extremely exaggerated and that we should not be sending over any planes for some time to come.”

“At that moment America had only 55 training planes, 51 of which were obsolete and four obsolescent.”

Reports historian Gilbert, on Pershing’s second day in London, “He learned that there would not be sufficient shipping to bring the American Expeditionary Force to France or to keep it supplied once it had arrived.”

“Fifteen ships had been sunk in British waters alone during the eleven days that Pershing was crossing the Atlantic.

“Indeed to guard against the possibility of torpedo attack, his ship had not responded to any of the frequent distress calls it had received.”

It is truly a desperate moment in this war.