First American Contingent Arrives in France

Virtually Untrained;

Who Will Command Them? Pershing Says He Will

Special to The Great War Project.

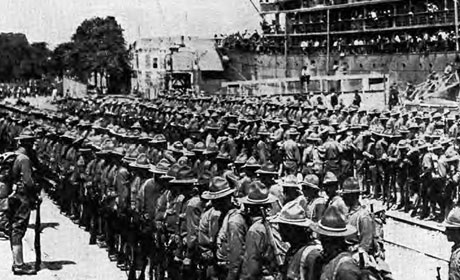

(18 June) At this moment in the war a century ago, the first significant contingent of American troops — some 14,000 – reaches France.

Their crossing the Atlantic was largely uneventful, according to historian Gary Mead, “apart from a few submarine scares.”

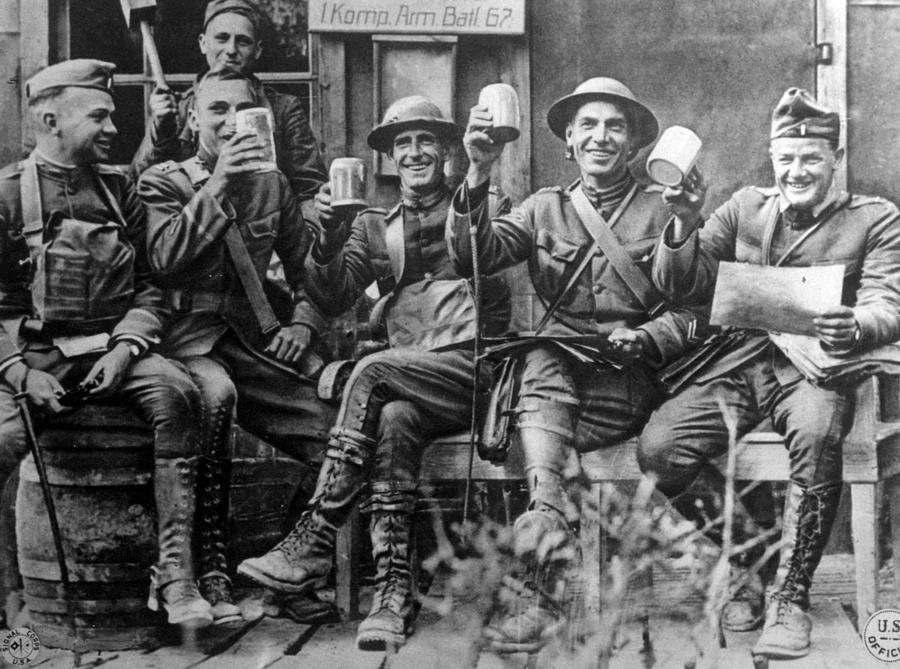

Some of the first Americans to reach France, June 1917.

The Americans are hardly battle-ready. According to historian Martin Gilbert, “this was to have had no effect at all on the battlefield. The men had first to train and to be reinforced by colleagues.”

Reinforcements are not expected to arrive for three months.

“America was at war,” Gilbert writes, ‘but in France her effort was necessarily focused on building up port and training facilities, supply lines, and store depots.”

“Some gaps were immediately evident.”

Gaps such as artillerymen arriving without their guns. Many of those with their guns do not know what they look like and how to use them.

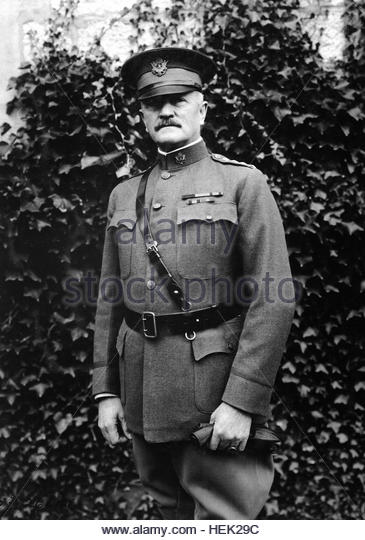

Reports Gilbert, “Even General John J. Pershing — commander of the American Expeditionary Force — was shocked by the poor quality of his men.”

General John J. Pershing, commander of American Expeditionary Force.in France.

Pershing is nothing if not a great logistics man. His first priority: “Establishing a network of training schools for his new arrivals. And initiating a vast apparatus of supply and preparation, essential to ensure American participation in the front line.”

“That participation was a long time away,” observes Gilbert, “The Americans had arrived but the question ‘Where are the Americans?’ was still on everyone’s lips.”

The answer is: still some time away.

There is also a fundamental question about whether the Americans are to remain as an independent force or to be “amalgamated” into France and British units. This proves to be a highly contentious matter, with Pershing insisting on keeping his men under his independent control, with the British and French arguing for amalgamation.

“Pershing,” reports historian Gary Mead, “had no intention of permitting any such amalgamation. The bitter clash over this issue further soured U.S. relations with Britain and France throughout the rest of the war.”

Writes two other historians, “Pershing and his staff thought amalgamation would disperse American strength.” They also believed a separate American force would have a greater psychological impact on the battlefield against the Germans.

First Americans reaching France, June 1917.

Nevertheless, at this moment in the war one hundred years ago, “there was little to amalgamate,” reports historian Mead. Writes one soldier in his diary, “It is too bad that our troops will have to train before going into the fight for so long a time. They can hardly be ready, even the first of them, before January 1918.”

Still despite all the rancor and disagreement over the Americans’ role, Mead writes that “the greatest asset of this first wave of the AEF was its boisterous good will, invaluable in a country so devastated by the war. Time would improve their mettle and vastly extend their combat skill to a level, almost matching their initial self-estimation. “