The Espionage Act Produces a Nation of Snoopers,

Trampling on the Bill of Rights

Special to The Great War Project.

(2 July) Opposition to the draft in the United States is widespread and sometimes turns violent.

“On the plains of Oklahoma,” writes historian Michael Kazin, “a band of tenant farmers sets out to fight the draft in quite literal fashion.”

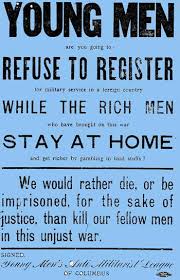

Anti-draft leaflet

“During the summer of 1917, a secret and loosely structured group known as the Working Class Union built a membership as high as thirty-five thousand with angry denunciations of the war and conscription. Unlike most radical organizations at the time, the WCU included both black and Native American members.”

“Along country roads,” Kazin reports, “the radicals hung posters that kindled the hope for insurrection.”

“Now is the time to rebel against this war with Germany, boys. Get together, boys, and don’t go. Rich man’s war. Poor man’s fight. If you don’t go, J.P. Morgan Co. is lost. Speculation is the only cause of the war.”

“Rebel now.”

Episodes like this prompt President Woodrow Wilson to take strong and potentially unconstitutional action against the opponents to the draft. His toughest measure is legislation known as the Espionage Act.

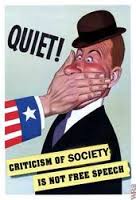

The danger from spies.

“On Flag Day, a century ago,” reports historian Margaret Wagner, “President Wilson delivered a speech on the grounds of the Washington Monument in which he declared… that there are many agents of Germany who “seek to undermine the American government with false professions of loyalty to its principles. But they will make no headway,” the president warned.

The next day the Espionage Act of 1917 passed. Its target: opponents of the war and what its supporters call seditious speech.

According to Wagner, “it became a powerful tool for suppressing any suspect or unpopular opinion, allowing fines up to $10,000…

…And imprisonment for up to twenty years for those convicted under its elastic terms.”

Wagner observes, “Overzealously enforced, the act would facilitate the very abandonment of tolerance the president had so darkly predicted.”

“Yet without the press censorship provision …” Wagner reports, “neither the president nor the Attorney General considered the Espionage Act sufficiently strong.”

Once the act was passed, all the nations’ law enforcement agencies moved quickly to put the war in their gun sights.

Wagner reports: “As soon as the country was officially at war the Attorney General assumed the initiative, urging all federal attorneys to be constantly vigilant and asking the nation’s police chiefs to keep watch on pacifists and German-Americans.”

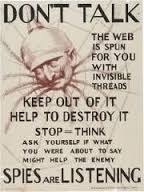

“His request that all citizens bring their suspicions to the Department of Justice initiated a tidal wave of often self-serving accusations.” Soon the Attorney General was boasting to President Wilson that he had, according to Wagner, “several hundred thousand private citizens keeping an eye on disloyal individuals and making reports of disloyal utterances.”

At the center of this snooper brigade is an organization calling itself the American Protective League. By mid-June a century ago, this group claimed more than 100,000 members nationwide in more than 600 branches.

Wagner reports, “as it continued to grow, eventually enlisting some 250,000 volunteers, the league branched out from its original intent to monitor enemy aliens and began peering at the behavior, statements, and finances of anyone suspected of disloyalty.”

The result: a widespread disregard of law in the United States, with warrant-less wiretaps, intercepting the mail, “and trampling all over the Bill of Rights.”