No One Knows for Sure,

But American Servicemen Soon Carry the Moniker Proudly

Special to The Great War Project

(6 August) More and more American troops, known as Doughboys, are arriving in France. One question on many minds, how did the American troops come to be known by the nickname Doughboy?

“It is far from clear,” writes historian Gary Mead, “why the four million officers and men who served in the AEF – the American Expeditionary Force — came to be known as doughboys.

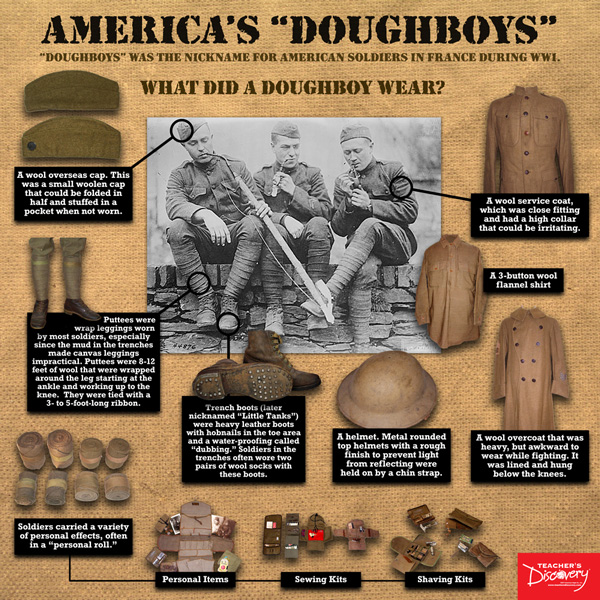

The American doughboy.

It’s a sobriquet, he observes, “which has not been favored by the passage of time.”

Mead writes, during the war, “the word carried connotations of battlefield heroism, grit, toughness, and physical endurance.”

Later the word would turn up, Mead sniffs, as “the brand name of an oven-ready bread mix.”

“French and British soldiers were initially at a loss to know what to call their new comrades. They soon hit on the nickname ‘Sammie’ after Uncle Sam.”

That failed to catch on.

The official Army magazine waged a strong campaign in favor of doughboy and turned up its nose at Sammie in a sharply worded editorial: “When in the fullness of time the American army has been welded by shock and suffering into a single fighting force…the American soldier will find his name….He does not know what that name will be.

“He simply knows it won’t be Sammie.”

The doughboy’s outfit.

But why doughboy?

It could refer, Mead speculates, to the size of the soldier’s pay. An American soldier received $30 a month, and in wartime France, that’s about ten times what a French soldier is paid.

Reports historian Mead, American soldiers felt loaded with dough.

Others believe it is a nickname picked up by American soldiers in Mexico during American operations there several years earlier. Possibly from the description of the adobe huts the American soldiers lived in during those days.

Some look even further afield, to the Philippines and American operations there.

According to one editorial in an American military magazine, “the word ‘doughboy’ originated in the Philippines. After a long march over extremely dusty roads, the infantrymen came into camp covered with dust. The long hikes brought out the perspiration, and the perspiration mixed with the dust to form a substance resembling dough; mounted soldiers called them doughboys.”

Some put the same story years earlier in the dust of America’s Indian Wars.

And some at that time said the buttons on a soldier’s shirt resembled a kind of dumpling that they put in soup.

The military magazine Stars and Stripes settles the dispute in early 1918. Backed by the commander of the American Expeditionary Force himself, General John J. Pershing, the magazine declared: “Doughboy is attaching itself to every living man who wears the olive drab.”

“Of late, with the original doughboys in the very vanguard of the AEF, the name appears… to have taken on a new accent of respect. Infantrymen, and artillerymen, medical department boys and signal corps sharks, officers and men alike, all of them are called doughboys and some of them are rather proud of it.”