Threatens Wilson’s Ability to Join the War.

Enter The Wobblies, The Loose Cannons of the Labor Movement

Special to The Great War Project.

(18 September) When President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Imperial Germany, there were many anti-war opponents in the United States.

There were those who based their opposition to the war on religious views. Also pacifists, conscientious objectors, and anti-draft activists.

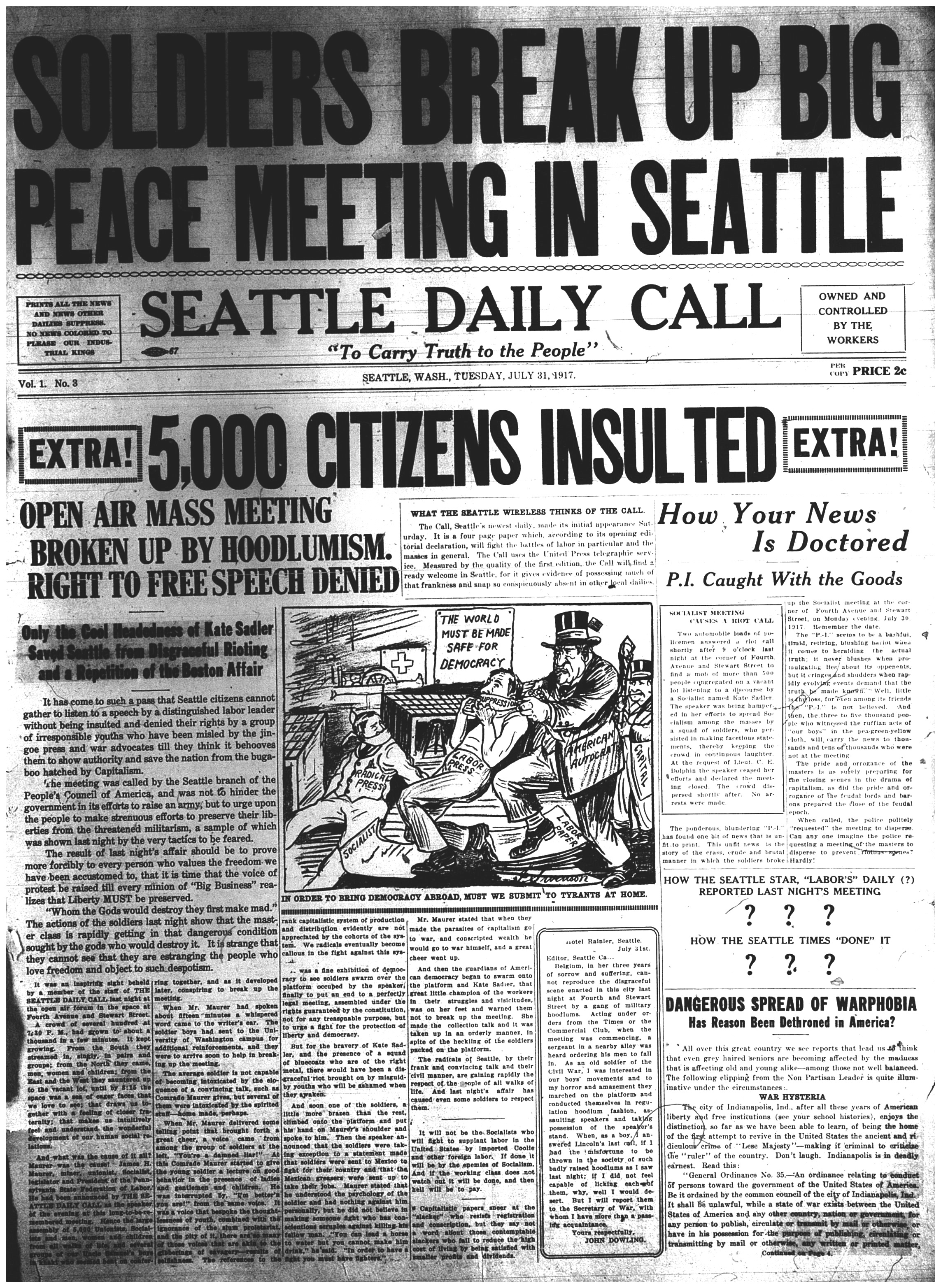

Anti-war meeting in Seattle.Free speech denied.

Once called up and sent to army training camps, many changed their minds and succumbed to putting on a uniform.

But “how this change was accomplished,” reports historian Thomas Fleming, “is not a pretty story. Harassed camp commanders, already grappling with shortages of everything, had little time to give much thought to the techniques of persuasion.”

“At most camps, the ‘conchies’ were left to the untender mercies of sergeants and lieutenants, who called them yellow-bellies, cowards, and pro-Germans.

Fleming reports, “The Mennonites, who resisted all forms of persuasion, had a particularly bad time….At one camp, a Mennonite resister was scrubbed with brushes dipped in lye. Sadists in another camp billeted them with men infected with venereal disease. Not too surprisingly many resisted this brutal treatment and were court-martialed.”

Anti-war strikes spreading.

“Some 110 were sentenced to the Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, army prison for terms ranging from ten to thirty years. One martyr to his faith and conscience wrote to his parents from his prison cell, “you can’t imagine how it is to be hated. If it wasn’t for Christ it would be impossible.”

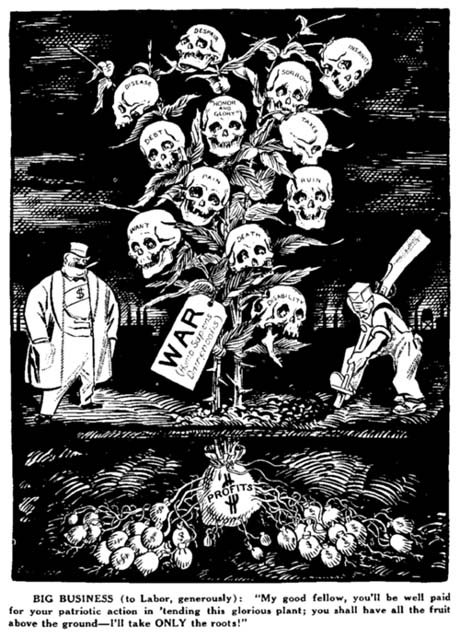

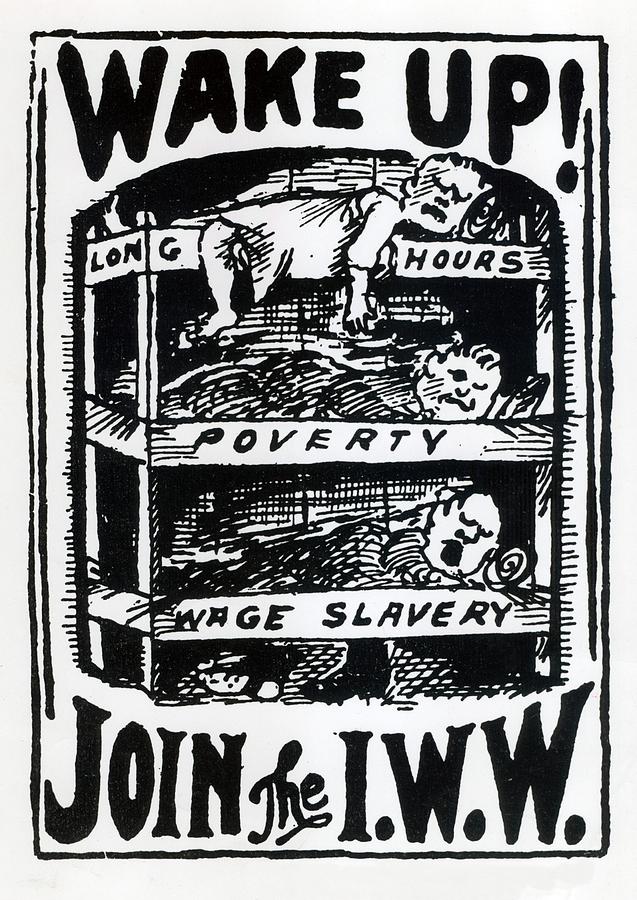

This, according to historian Fleming, “meant deep trouble for the radical union, the Industrial Workers of the World,” also known as the IWW or the Wobblies. “The Wobblies were the loose cannons of the labor movement…the IWW aimed at unionizing the unskilled and uneducated workers largely ignored by the other craft unions in the labor movement.”

According to Fleming “the union returned with interest the violent hostility of the employers and their friends” in government.

“Wobbly rhetoric wreaked with class warfare and calls for revolution. Their constitution candidly declared that they were out to abolish the wage system.”

So, Fleming writes, “not too surprisingly, the IWW took a dim view of Wilson’s war. “While being opposed to the Imperial Government of Germany,” the IWW leader Big Bill Haywood proclaimed, We are likewise opposed to the industrial oligarchy of this country.”

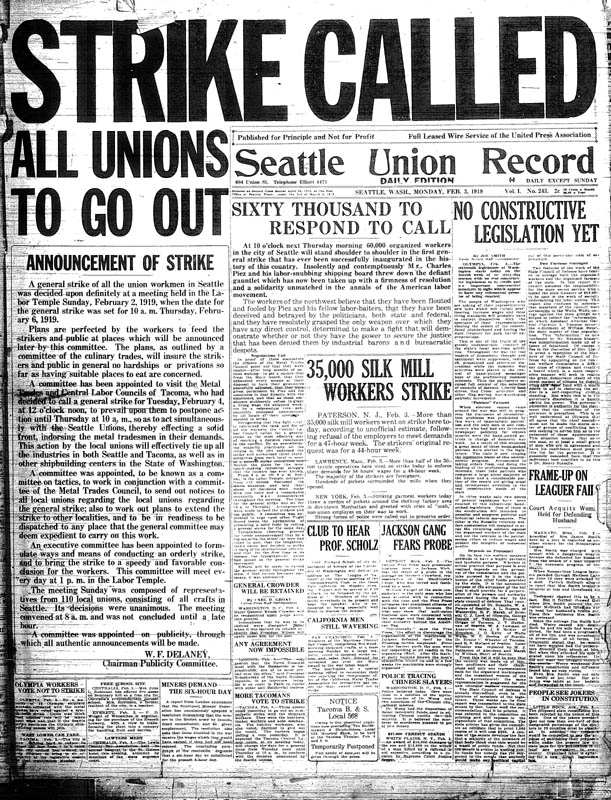

The strike was the weapon of choice for the Wobblies. By mid-year in 1917, the Wobblies were conducting strikes across the United States, involving tens of thousands of workers and miners.

Wobbly anti-war leaflet.

In the lumber and copper industries, they had launched strikes in the aircraft industry, and in the construction of barracks for the thousands of trainees. They interrupted the flow of weaponry to the British and French, Fleming reports.

Wobbly recruitment rhetoric.

The owners of the mines and industrialists, backed by the newspapers, charged that the Germans and German money were behind these “treasonous” actions. They used the courts to put them away. On September 28th a century ago, reports historian Fleming, “166 IWW officers were indicted using their own words to prove that they had violated eleven laws related to the war, conspired to interfere with employers trying to fulfill vital government contracts, urged fellow Wobblies to refuse to register for conscription, and plotted to create insubordination in the armed forces.”

Observed Fleming: “There was little doubt about what the Wilson administration had in mind. “Our purpose as I understand it,” wrote one government attorney in Philadelphia, “is to put the IWW out of business.”