Passchendaele in Flanders,

Victory or Disaster?

Either Way, Another Blood-soaked Horror.

Special to The Great War Project

(12 November) By November 10th, a century ago, the battle for Passchendaele in Flanders has come to an end. Among those taking part are the Canadian forces. Although meager in number, they figure prominently in the outcome.

The Canadians advance a bare five hundred yards, reports history Martin Gilbert, “in the face of a massive German artillery bombardment of more than five hundred guns and continual air attacks.”

More than half a million soldiers died at the 3-month stalemate at Passchendaele.

Passchendaele became just another “war of attrition,” writes historian Michael Neiberg, “that cost enormous casualties for negligible gains of territory.”

The numbers for the battle are staggering.

“Since the start of the British offensive on the last day of July,” Gilbert reports, “British forces had gained four and a half miles of ground. The cost was 62,000 dead.”

Some 164,000 are wounded.

Mud is everywhere.

As for the Germans, they lose 83,000 killed and as many as a quarter of a million wounded. Some 26,000 Germans are taken prisoner.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George hails Passchendaele as a great victory. But he adds, “when I look at the appalling casualty lists, I sometimes wish it had not been so.”

“A deep reluctance,” observes historian Gilbert, “to be in the casualty lists could be seen that month in the statistics following the call-up in Canada. So unpopular was the prospect of military service in Europe, that of the nearly 332,000 able-bodied Canadians who are eligible to be drafted, less than 22,000 reported for military service. More than 310,000 applied for exemptions.”

It was an indication, Gilbert writes, of the growing grasp of the reality of this war.

More widely, “the war sapped daily life [in Britain] in countless ways,” writes historian Adam Hochschild.

By this time a century ago, “one British city after another began rationing food, indeed everything.”

With enormous quantities of coal and 370 locomotives diverted to France, some 400 smaller railway stations closed. Buses, trolleys, and trains were always overcrowded.”

Another winter brought exceptionally cold weather. Coal rationing is imposed in London. “People lined up to buy everything.”

Newspapers shrank as news print became scarce.

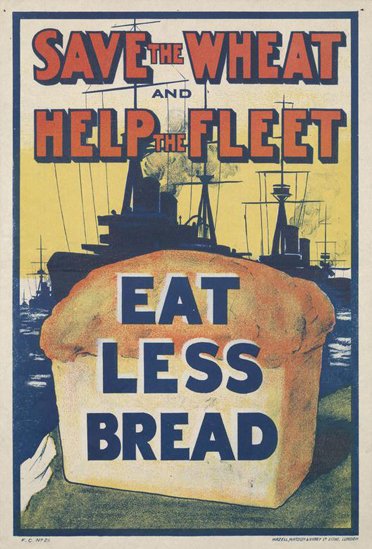

British rationing poster.

This is a list of things that were increasingly hard to get: bacon, butter, margarine, matches, and tea!

Long lines appeared for all these products. “Wheat husks and potatoes were used as filler in bread,” reports Hochschild.

And this incredible fact: “throwing rice at weddings was made a criminal office.”

Even conscientious objectors in prison saw their bread ration cut in half to eleven ounces a day.

The public is turning cynical, and this cynicism is reflected in the newspapers. “We’re telling lies,” declares the publisher of one newspaper who has already lost one son in the war. We dare not telling the public the truth, that we are losing more officers than the Germans.”

Reluctantly, one of Britain’s most influential publishers writes to Prime Minister David Lloyd George: “We are slowly but surely killing off the best of the male population of these islands.”

This was Passchendaele.

We’re not losing the war, he writes in The Daily Telegraph, “but its prolongation will spell ruin for the civilized world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it.”