Wilson’s Fourteen Points Excite the World.

The American President an Instant Hero

Special to The Great War Project.

(14 January) So far, in this war, from its beginning in the summer of 1914 until the start of this new year, a century ago, there has been no comprehensive statement of the war aims of both sides.

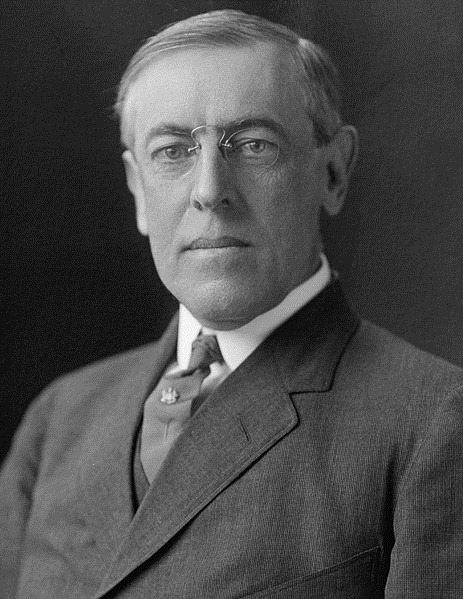

But with the entry of the United States into the war, stating the aims of the belligerents, especially the war aims of the United States under President Woodrow Wilson, has become unavoidable.

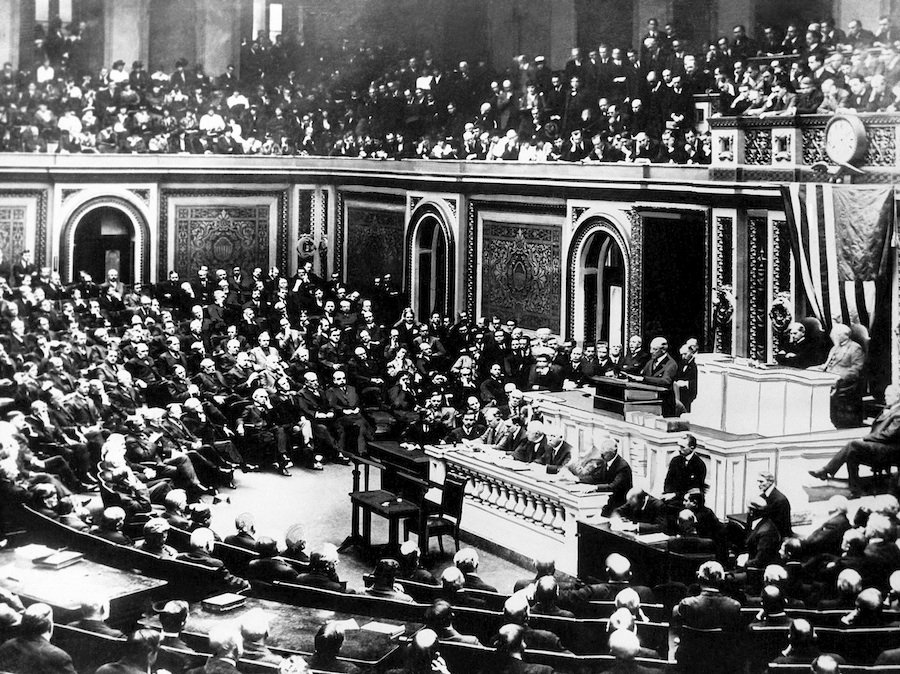

Wilson Presents his Fourteen Points to Congress, January 8, 1918.

At first, the aims appear limited. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George delivers a speech in London, stating it is not the aim of the Allies to seek the breakup of Austria-Hungary.

This is just one indication of what the belligerents, and their weaker allies, are seeking. “Behind every front line,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “political movements were stirring with a new enthusiasm.”

They are war-weary, and they are looking to negotiation to satisfy their ambitious plans for statehood.

But to fulfill these goals, would require the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, just now not a war aim of the Allies. “The main precondition for many of these hopes,” Gilbert reports, “was the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, which could not be taken for granted.”

Wilson

Into this troubled political whirlwind steps the American president, Woodrow Wilson. It’s nearly a year since America entered the war, but so far the US has made little difference. In a speech to the American Congress on January 8th Wilson seeks to change that, with nothing less then a reformulation of the world order, “a peace program for Europe,” Gilbert reports, “based upon fourteen separate points, essentially democratic and liberal in outlook.”

Among them are goals and principles that Wilson sees as essential for maintaining international peace in the future.

Freedom of the seas. Transparency when it comes to international negotiations. The removal of economic barriers to trade.

And more specifically, Wilson declares, Germany must withdraw from all Russian territory, as well as from the Belgian and French territory it is occupying.

What’s more, according to Wilson, the peoples of Austria-Hungary must be given freedom to development on their own. Restore an autonomous Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro.

As for the Ottoman Empire, Wilson calls for assuring the sovereignty of the Turkish portions, but separate out non-Turkish regions, “the other nationalities inside Turkey (Read Armenia) to be assured of their autonomy.

Another aim: establish a united and independent Polish state.

The fighting continues.

And finally, Wilson calls for “the formation of a general association of nations to guarantee political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.”

The Fourteen Points, according to historian Martin Gilbert, “were intended as a counter to the growing appeal of Russian Bolshevism among the soldiers of Germany and Austria, and to be more attractive than a Bolshevik-inspired peace.”

“They did not satisfy to the full the hopes for statehood that had been aroused,” Gilbert reports, “but the race for national patronage was affecting both sides.”

Quite literally, the Fourteen Points outlined nearly all the terrible political conflicts that were to come in the century that was to follow.

Wilson’s stock soars. The leaders of the Allied powers did have some reservations about the Fourteen Points, “but millions of people,” writes historian Margaret Wagner, “embraced his plan for a better postwar world.”