Some Americans Will Fight in the Allied ranks;

Others To Form A Separate American Army in France.

Minorities See Opportunities.

Special to The Great War Project

(7 May) The quarrel of the Allies ends in May a century ago, with a compromise that pleases no one.

The bitter debate centers on how to deploy the hundreds of thousands of American troops now or soon to be in France. General John J. Pershing, the American commander, insists they form a separate American army to fight the Germans. Britain and France want them to fight the Germans, but under French and British command.

Pershing offers the compromise: split the difference. Reports historian Martin Gilbert, “the French and British had no option but to accept.”

That May a century ago, the hundreds of thousands of American infantrymen and machine gunners being transported across the Atlantic in British ships (some 130,000 men) and an additional 150,000 Americans in June – all of them will join the Allied lines.

By the end of May there would be 650,000 American troops in France. “As a result of Pershing’s compromise,” writes Gilbert…

“two-thirds of them would not be joining the line until they could do so as an American army.

Marshall Foch, the French supreme Allied commander, “was depressed,” reports Gilbert. Georges Clemenceau, the French prime minister, was angry, and the British prime minister, David Lloyd George, was “bitterly disappointed.”

General Pershing with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

He writes to the British Ambassador in Washington: “It is maddening to think that though the men are there, the issue may be endangered because of the short-sightedness of one general and the failure of his government to order him to carry out their undertakings.”

That same May a century ago, reports Gilbert, “national aspirations began to surface among the minorities in the Austrian army.”

Austria, although greatly weakened, was still an ally of Germany, and still at war. In mid-May “there was a mutiny in the heart of Austria,” writes Gilbert, “when an infantry platoon captured the barracks and ammunition stores, looted the food stores, and destroyed the telephone and telegraph lines.”

The mutineers are largely Slovene. They threaten to walk off the battlefield. Their cry: “Let us go home comrades. This is not only for us, but also for our friends on the fronts.”

“The war must be ended now. Whoever is a Slovene, join us. We are going home. They should give us more to eat and end the war. Up with the Bolsheviks. Long live bread, down with the war.”

Reports Gilbert, “the mutiny was quickly suppressed, and six Slovenes were executed.”

But mutiny spreads quickly, from the Balkans to central Europe. It is just as quickly put down.

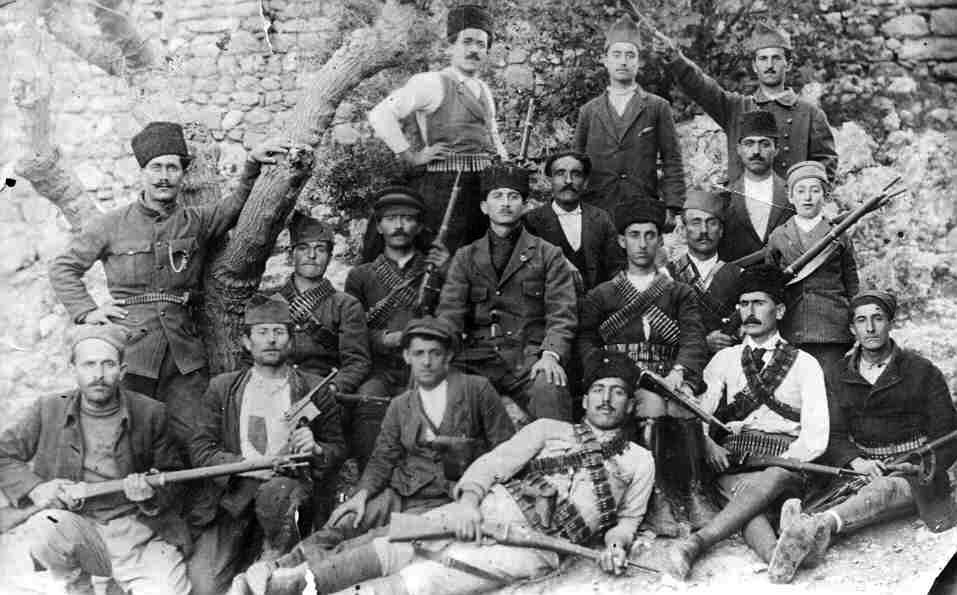

Uprising of Armenian fighters.

Perhaps the most significant nationalist impulse is that of the Armenians still living in Turkey. According to historian Gilbert, “Turkey was driving the Armenians out of what was left of their homeland,” after the genocidal attempt three years earlier to destroy the entire Armenian community in Turkey.

“The Armenians fought tenaciously,” according to Gilbert, “but the Turks were ultimately victorious and 5000 Armenians made their escape over the Caucasus mountain passes.”

The Armenians declare their independence that May a century ago, but their rising is put down.

“It was a short-lived culmination of long-held aspirations, reports historian Gilbert.”

Armenian child lies dead on the battlefield.

As a result, hundreds of thousands of Armenians will soon meet their death.