Sees an Essential Part of the Peace Treaty.

The Press Sours on the President,

He Perseveres Nevertheless.

Special to The Great War Project.

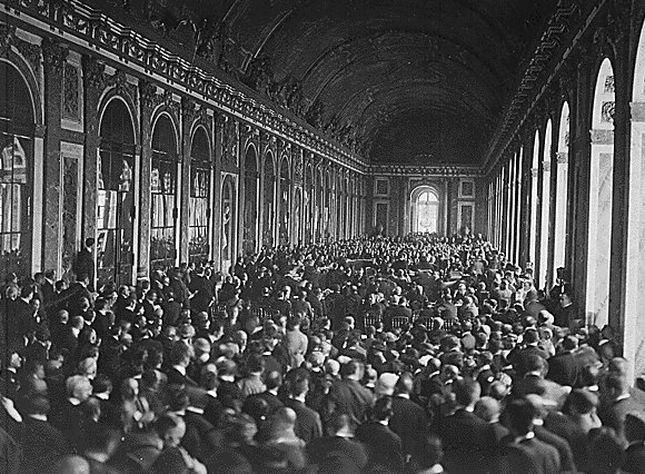

(29 January) Paris is awash with journalists, sent from around the world to cover the peace conference.

And increasingly, the press was becoming hostile to the peace process. Just look at the first of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points: “Open covenants openly arrived at.”

The peace conference at work.

So writes historian Thomas Fleming. “Both the press and the American people assumed this meant they would have access to all the details of the peace conference. Wasn’t this what Wilson’s ‘New diplomacy’ meant?”

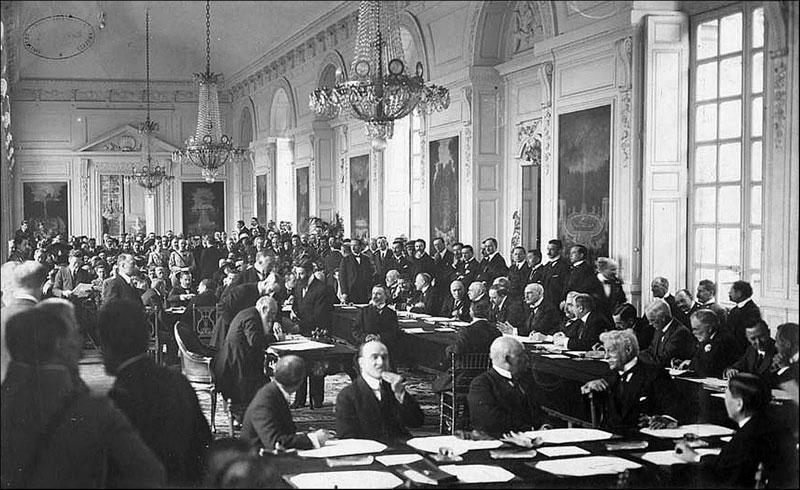

“Instead,” reports Fleming, “they found themselves barred from all sessions of the Council of Ten, (the Big Five and their foreign ministers), which seldom issued more than five sentences to summarize its doings.”

The working peace conference.

“This code of silence left the reporters reduced to peering through the doors at the relatively rare plenary council sessions, where little was debated and the lesser delegates were simply asked to ratify the decisions of the major powers.”

Writes Fleming, “Wilson had seen open covenants as a way to ban secret treaties, such as the pre-war accords signed by the British Foreign Secretary, signed with the French and the Russians and the mercenary deal the Allies had cut with the Italians in 1915.

“Wilson never dreamed people would want to know about the give-and-take of negotiations between foreign ministers and leaders.

Observes Fleming, “But the reporters were not interested in the president’s clarifications. They called the plenary sessions washouts and started writing about a gag-rule that made a mockery of Wilson’s idealistic promises.”

It was the old-style diplomacy in the dark all over again.

Wilson did make an effort to remedy the problem. He authorized an American diplomat to speak on his behalf, but it was a matter of too-little, too-late.

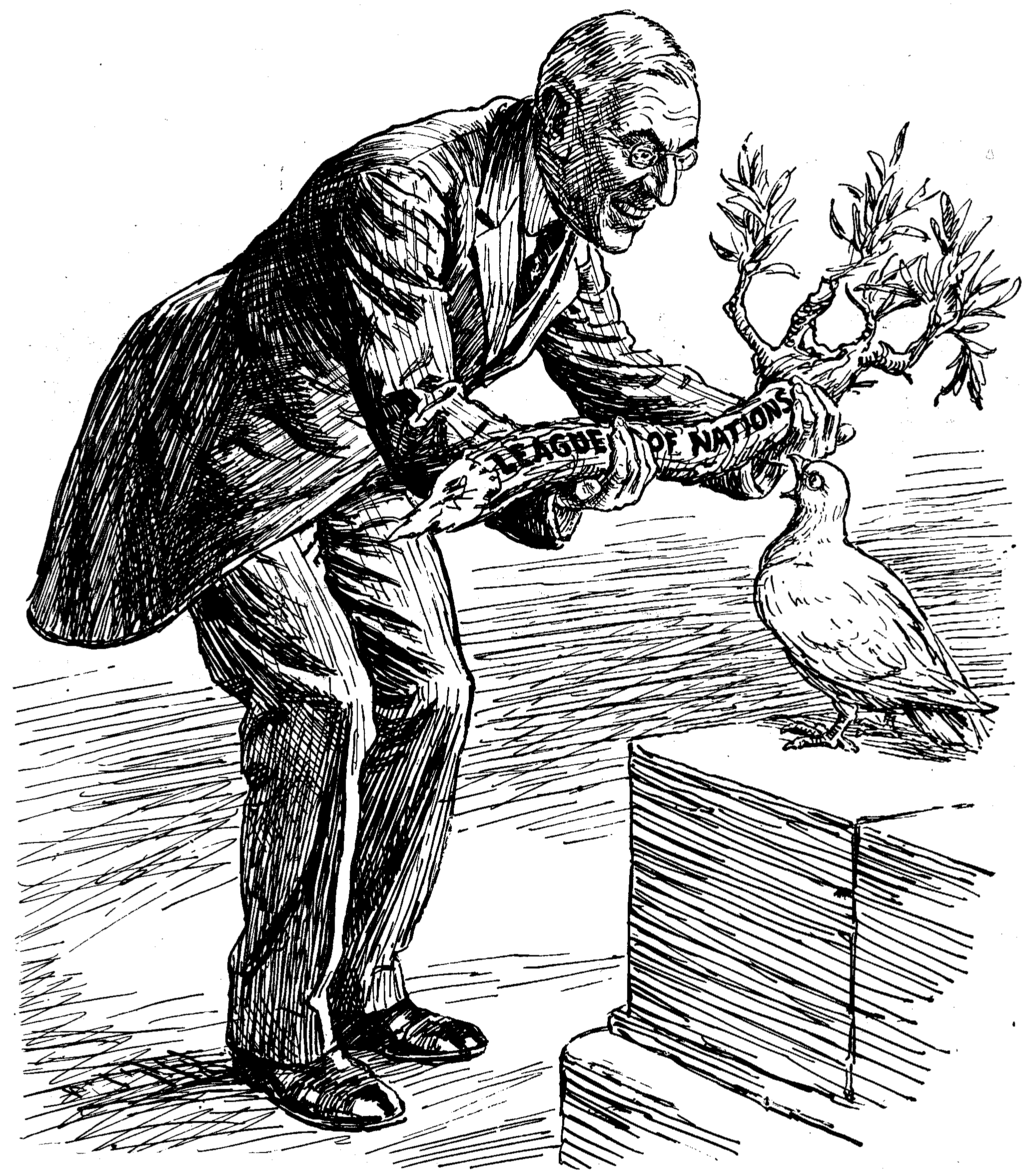

Cartoon: Wilson and the bird of peace.

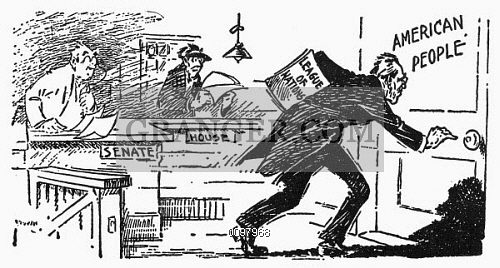

Reporters wanted access to Wilson himself, access Wilson declined to provide. He did hold two press conferences in France, but he insisted everything he said was off the record.

Fleming reports: “When two reporters quoted him, he was infuriated and he never talked to a news reporter again.”

The other Allied leaders met regularly with the press of their individual countries.”

Writes historian Fleming, the American press contingent in fact was eager to support the American positions at the peace conference, but only if they knew what it was.

“It was not surprising then that under this state of affairs they began to loose confidence in American leadership at the conference.”

Meanwhile, reports historian Fleming, Wilson persevered in his single-minded struggle for the League of Nations, which he saw as the eventual answer to almost every problem facing the conference.

Wilson and the League.

On January 25th he goes before the conference to propose the creation of a special commission to hammer out the structural details of a league. By this time he has persuaded Clemenceau and Lloyd George of the necessity to create such a league as an essential part of a peace treaty.

He names himself as chairman of the commission that will hammer out the details.

1 comment for “WILSON FIGHTS FOR A LEAGUE OF NATIONS”