Millions Go Without.

Who Can Solve the Growing Disaster?

It Falls to the United States;

Special to The Great War Project.

(20 February) The powers at the peace conference soon realize they have taken responsibility for vast areas of Europe and indeed much of the world.

Writes historian Margaret MacMillan, it is a role they have failed to anticipate. “The peacemakers soon discovered that they had taken on the administration of much of Europe and large parts of the Middle East.”

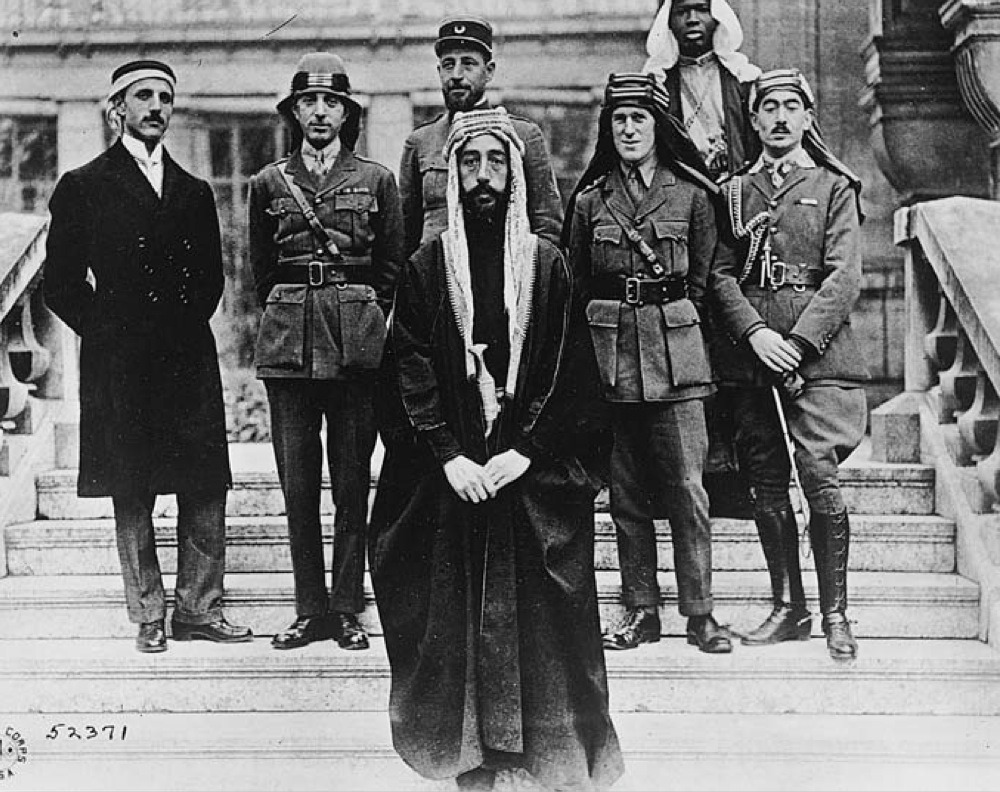

Persians at the peace conference

“Old ruling structures had collapsed,” she writes, “and Allied occupation forces and Allied representatives were being drawn in to take their place. There was little choice. If they did not do it, no one would.”

“Or worse. Revolutionaries might.”

Arabs, not pictured here, would turn to the conference too..

One example: “In Belgrade, a British admiral scraped together a small fleet of barges and sent them up and down the Danube carrying food and raw materials.”

This brought about a meager revival in trade and industry. “But it was a stopgap measure.”

“The war,” MacMillan reports, “had disrupted the world’s economy and it would not be easy to get it going again. The war had left factories unusable, fields untilled, bridges and railway lines destroyed.”

“There were shortages of fertilizer, seeds, raw materials, shipping, locomotives. Europe still depended largely on coal for its fuel. But the mines in France, Belgium, Poland, and Germany were flooded.”

“From all quarters of Europe,” historian MacMillan reports, “came alarming reports of millions of unemployed men, desperate housewives feeding their families on potatoes and cabbage soup, emaciated children.”

In the first cold winter of the peace, Herbert Hoover, then the American relief administrator, warns the Allies that some 200 million people in the enemy countries, and almost as many again in the victors’ and the neutral nations, faced famine.”

Germany alone needed 200,000 tons of wheat per month and 70,000 tons of meat.

In the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, “hospitals have run out of bandages and medicine.”

In what became the new state of Czechoslovakia, a million children are going without milk.”

“In Vienna more babies were dying than were surviving. People were eating coal dust, wood shavings and sand.”

“The humanitarian case for doing something was unanswerable. So was the political one. So long as hunger continued to gnaw, warned President Wilson, “the foundations of government would continue to crumble.”

Hunger in Europe during the war and after.

The surplus food is available. So are the ships to transport it. But where is the money? “The European Allies could not finance relief on the scale that was needed.” Germany has gold reserves but the victorious Allies – France in particular – blocks Germany’s use of its gold for any purpose other than war reparations.

That leaves the United States.

“But Congress and the American people are ambivalent about embarking on such an enormous task.”

President Wilson reluctantly agrees but only if he can put Herbert Hoover in charge. Hoover has made a reputation for himself as a leader in distributing humanitarian aid, despite the charge by some European leaders that Hoover would become dictator of Europe.

Herbert Hoover in Europe.

But to Wilson and many Americans, Hoover is a hero. During the war, he had organized a massive relief operation for German-occupied Belgium.

For President Wilson, it’s Herbert Hoover or no one.