French Appetite for Revenge Still in Charge.

Germans Lose Confidence in Wilson.

Such a Scoundrel.

Special to The Great War Project

(7 May) The shock of the draft treaty deepens.

So writes historian Thomas Fleming. On the afternoon of May 7th a century ago, the German foreign minister and other German dignitaries are ushered into one of the immense royal palaces of the French kings.

The Germans sit across from the big three: Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and President Wilson.

The Peace Conference.

The press reports that the Germans are seated at the “table of the accused.” Clemenceau rises and begins by saying that “this was not the time nor the place, for superfluous words.”

He “spat out a venomous speech,” Fleming reports. Addressing the Germans directly, he says the hour has struck for the weighty settlement of your account.”

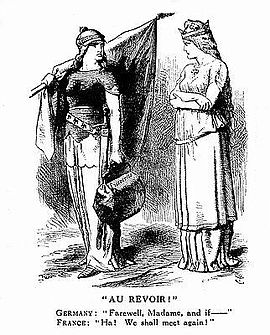

The French appetite for revenge, Fleming concludes, is still in charge.

“The Germans registered shock and disbelief,” reports Fleming.” Clemenceau is telling them there will be no face-to-face negotiations.

Then it was the German prime minister’s turn. He did not stand to deliver his remarks. Some see this as a sign of disrespect, but others see he is terribly nervous and unable to stand.

No peace at the peace conference.

He begins by saying, “we know the intensity of the hatred that meets us” and the blame placed on them. The German leader confesses he can never agree. “Such a confession that fastened blame for the war he could never accept. “Such a confession in my mouth would be a lie.”

He tells his audience the continuing British blockade is killing hundreds of thousands of German noncombatants. Then he reminds them that they had offered peace on the basis of Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

One British delegate dismisses these words as “the most tactless speech” he had ever heard. Clemenceau’s face turned a bright red. Lloyd George grew so angry, he snapped an ivory letter opener in half.

After reading the treaty all the way through, Wilson turns to one American delegate and confesses,

“If I were a German, I think I should never sign it.”

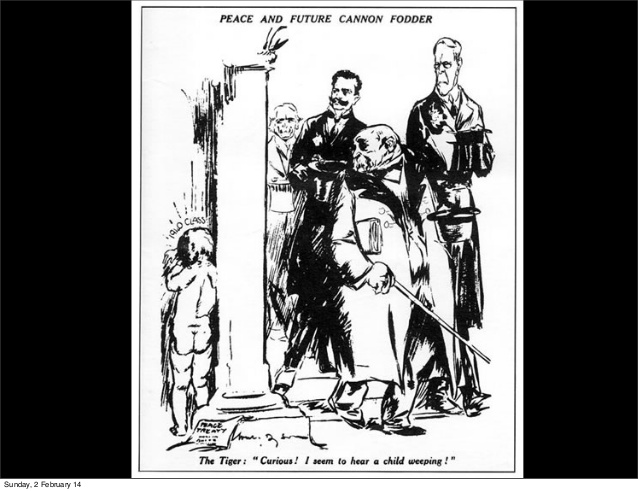

The Germans spend the night translating the full text of the treaty. “By dawn,” writes Fleming, “they saw what confronted them. Along with the confession of guilt for the war, were reparations that would be decided later, which meant that Germany’s economy would be at the mercy of the victors for as long as they pleased.”

Added to this, Fleming reports, are the loss of crucial coal fields to the Poles and the French, the separation of the Rhineland, the Saar, and Upper Silesia from what had been Germany, the loss of the port city of Danzig, now attached to Poland, the all-but-total destruction of their army and navy…

…and a demand that the Kaiser and an unspecified number of other leaders be surrendered for trial as war criminals.

“The terms,” observes Fleming, “drive one member of the German delegation –a socialist — to drink. In an alcoholic rage he smashes glasses and shouts:

Germans under pressure.

“I believed in Woodrow Wilson until today. I believed him an honest man. And now that scoundrel sends us such a treaty!”