Double Cross at Scapa Flow

Berlin Concludes Resistance is Futile.

Wilson Takes Charge

Special to The Great War Project

President Wilson digs in his heals. He will make no changes in the draft treaty, despite pressure from a growing number of delegates to do so.

So reports historian Thomas Fleming. And when the British PM Lloyd George learns of Wilson’s unmovable stance, “he does another back flip of his own” and abandons his effort to modify the treaty.

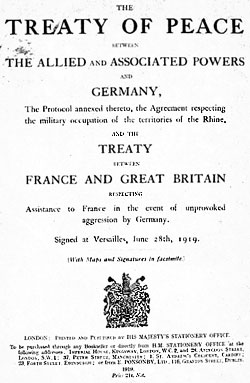

Peace Treaty signed.

Meanwhile, the liberal German government huddles in the town of Weimar in south western Germany.

The Germans have been left with no good choices. “A refusal to sign,” writes Fleming, “would mean a renewal of the British blockade and the invasion of Germany.

The nation would collapse into chaotic fragments.”

So sign the treaty, and let the Allies learn that “Germany would not and could not fulfill most of its terms.”

The German cabinet is deadlocked. Half argue in favor of signing, half reject the treaty.

The Peace Treaty.

“The irreconcilables were especially incensed by the war guilt clause,” Fleming reports, “and the articles that required the surrender of the Kaiser for trial as a war criminal, along with an as yet unnamed list of generals and admirals.”

There is no agreement among the Germans. The liberal German government collapses.

Only two days left in the Allied ultimatum: sign or face invasion.

Then a shock from the German side. News reaches Paris “of an event that scotches any hope the Allies would accept a deletion of the shame paragraphs.”

The German fleet, interned at sea at Scapa Flow north of Scotland, is scuttled on orders from its commanding admiral.

“The admiral decided the navy’s honor required him to send the five battle cruisers, nine battleships, seven cruisers, and fifty destroyers to the bottom of the sea to prevent them from being used to bomb German ports in the new war that seemed likely to erupt at any moment.”

British PM Lloyd George and the rest of the British delegation are enraged and not a little mortified by the way the Germans got away with this double cross under the noses of their Grand Fleet.

Fleming goes on:

“The French wonder aloud if the British let it happen to make sure they remained the world’s dominant sea power.”

Scapa Flow

“French PM Clemenseau had expected to get a hefty percentage of the German ships.”

So reports historian Fleming, “Woodrow Wilson took charge of the situation. He told the Germans that the time for discussion is past.” His threat is merciless. The Germans have less than twenty-four hours to sign, or be invaded by thirty divisions backed by aircraft, and a renewed blockade that would cut off every scrap of food from the outside world.

This was using the blockade and its impact on the German people as the ultimate weapon.

The Germans reckon they would fight again if the military calculates there was even the smallest assurance the German army could hold its own.

But the German leaders – political and military – quickly conclude resistance is hopeless.

Germans sign..

The German leaders send a note to Paris: “Yielding to overwhelming force the government of the German Republic declares that it is ready to accept and sign the conditions of peace imposed by the Allied and Associated powers.”

Watching the allies build this bad peace brick by brick, so methodically, is very sad.

It seems this column is coming out a month early? The Scapa Flow scuttling was June 21 1919. Germany’s Admiral, Ludwig von Reuter, had the possiblity of scuttling the ships as early as January 1919, but did not start planning for it in earnest until May 1919 when the terms of the Versailles Treaty were more clarified.

Noted.