It’s a Noble Duty,

Not a Chance.

Meanwhile, Mood Worsens in Paris.

Special to The Great War Project.

(1 June) In mid-March a century ago, President Wilson’s closest adviser, Colonel House, assures the other Allied leaders that the United States “would undoubtedly take a mandate.”

Privately the belief takes hold that the Americans are seriously thinking it would be Armenia.

Fighters of the Armenian Legion

British PM Lloyd George is delighted, according to historian Margaret Macmillan, at the prospect of the Americans taking on “the noble duty.”

But House as he so often does, is exaggerating. Wilson warns the Supreme Council at the peace talks that…

“he could think of nothing the people of the United States would be less inclined to accept than military responsibility in Asia.”

Macmillan concludes: “It is perhaps a measure of how far Wilson’s judgment had deteriorated that when Armenia comes up at the Council of Four at Versailles, he agrees to accept a mandate, subject he adds, to the consent of the American Senate.”

Map of the proposed mandates.

The French are enraged. This mandate would effectively take territories from the eastern shore of the Black Sea to the Mediterranean in the west, earlier promised to the French.

French leaders complain: “They must be drunk the way they are surrendering a total capitulation, a mess, an unimaginable shamble.”

“Many other schemes for the Ottoman empire were floating around the conference rooms and dinner tables in Paris. What was left out was the inability of the powers to enforce their will.”

“They seem to think,” observes Macmillan, “that their writ runs in Turkey, in Asia. Almost everyone in Paris would simply do as they were told.”

Britain’s Lord Balfour sums it up:

“I am quite unable to see why heaven or any other power should object to our telling the Moslem what he ought to think.”

“That,” Macmillan writes, “went for the Arab subjects of the Ottoman empire as well.”

Meanwhile, the dickering at the Paris Peace Table is wrapping up. “On May 4,” reports Macmillan, “the council of the Big Four gave orders that the German treaty should go to the printers.”

“Like so many of their countrymen,” Macmillan writes, “the Germans at the peace conference thought President Wilson would ensure that the peace terms were mild.

After all, Germany had done as Wilson himself had suggested and become a republic.”

“That alone had shown its good faith.”

“The country undoubtedly has to pay some sort of indemnity, but nothing toward the costs of the war. It would become a member of the League of Nations. It would keep its colonies.”

“And the principle of self-determination would work in its favor.”

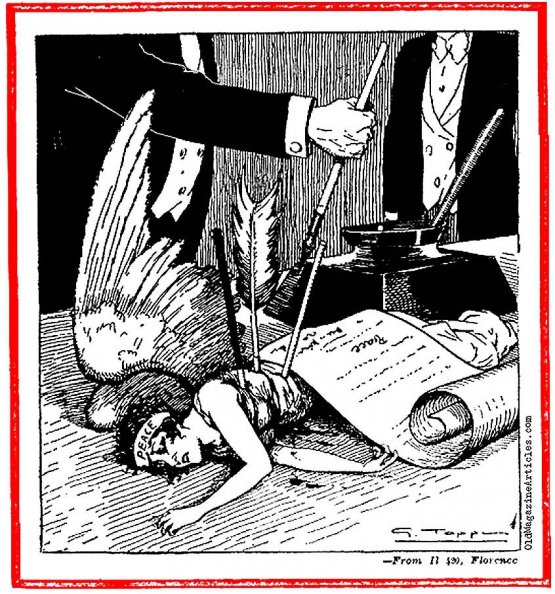

Treaty cartoon, killing peace.

Historian Macmillan goes on, “In the first months of the peace, the Germans clutched at the Fourteen Points like a life raft, with very little sense that their victors might not see things the same way.”

There was also perhaps understandably a reluctance to think about the future.

“Especially the one that was being shaped in Paris.”

The two sides meet for the first time a century ago and promptly misunderstand each other. “This is the most tactless speech I’ve ever heard,” Wilson says of the German foreign minister’s remarks, “The Germans are really a stupid people. They always do the wrong thing.”

Things got worse after that.

A