Bombs from Airships and Torpedoes from Submarines.

Stalemate and Changing Warfare at the Aisne.

Special to The Great War Project

(22-23 September) On this day a century ago, the war claims victims from the air and from under the sea.

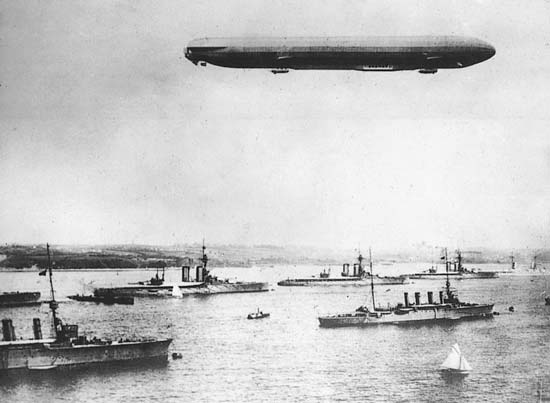

Four British planes attack German Zeppelins at their bases in Cologne and Dusseldorf. This just two days after a German airship makes a bombing run against Nottingham in England. It is the first British air attack on Germany, a successful surprise attack.

The Germans mount Zeppelin bombing raids as early as the first week of the war in August 1914, starting with attacks against the Belgian city of Liege. Then German air attacks target Antwerp in Belgium in early September.

The Germans also mount small bombing runs using airplanes against Paris and English Channel ports.

The initial Zeppelin attacks utilize the simple dropping of artillery shells. The Germans do not have specialized bombs they can drop from Zeppelins. Given their size and construction, the airships are highly vulnerable to ground fire as they drop their shells at low altitude. So they adjust their attacks to a higher altitude above the range of Allied aircraft.

Thus the British attacks on the airships at their German bases.

On the Eastern Front, the Germans also use the Zeppelin for bombing runs against the Russians during the Battle of Tannenberg.

On this September 22nd a century ago, a single German submarine, designated U-9, sinks three British cruisers in one hour’s time. More than 1400 sailors and officers drown.

The war is global. On the same day, a German warship bombards the Burma Oil Company naval fuel facility at Madras in British India. And “in the Far East,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “British, Australian, and Japanese troops were moving against the many scattered German ports and islands.”

On the Western Front, there is continuous fighting at the River Aisne. According to historian Max Hastings, British casualties there average 2,000 each day. Hastings quotes the description of one soldier:

“Troops are beginning to get downhearted here, as the Germans have proven themselves to be a better army that we thought.”

Both sides dig in deeper at the Aisne as the days bring no respite from continuous artillery attacks and rifle fire. But warfare is changing right before the eyes of the soldiers.

“Had we known it,” writes one officer quoted by Hastings, “this was the beginning of trench warfare. There was of course no wire, and trenches were far apart, the intervening ground being covered with fire.”

Snipers took many British solders so there is no movement during daylight hours. The weather turns hot and the smell of dead bodies and dead horse carcasses “was dreadful,” writes the officer.

The Battle of Aisne changes perceptions of warfare from the lowliest trench soldier to the highest general. Sir John French, the British commander-in-chief, writes to King George V, “I think the battle of the Aisne is very typical of what battles in the future are most likely to resemble…the spade will be as great a necessity as the rifle, and the heaviest calibers and types of artillery will be brought up in support on either side.”

Thanks for this. In addition to the U9’s sinking of HMS Aboukir, HMS Hogue, and HMS Cressy (three nearly obsolete armoured cruisers which had been awarded the less-than-desirable sobriquet of “The Live Bait Squadron”), and SMS Emden’s attack on Madras, one other event occurred on 22 Sept 1914: Admiral von Spee’s East Asia Squadron shelled Papeete, French Polynesia. This was a minor German tactical victory, but a strategic blunder, because it both notified the British Admiralty of the whereabouts of the German warships, and (more importantly) it consumed valuable ammunition resources which could not be replenished. When von Spee’s ships met the Royal Navy some weeks later, they came to regret this loss immensely.

Many thanks for that addition David.