American Ships Seized; Believed Carrying Copper for Germany.

Special to The Great War Project

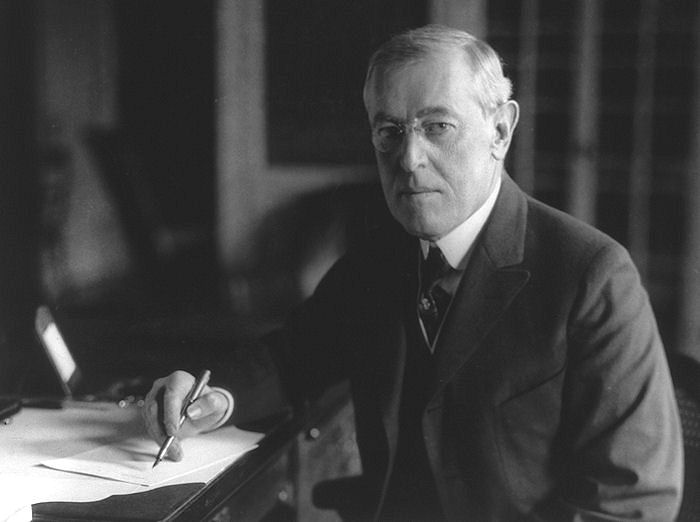

(10-11 December) Trouble breaks out between Britain and the United States in the late fall of 1914 – “a state of near crisis,” according to Arthur Link, biographer of the American president Woodrow Wilson.

The issue is neutrality – what the United States can and cannot do as a neutral nation.

“The first external problem of neutrality,” writes Link, “was the easily stated but awesomely difficult one of finding the line where the rights of British sea power under international law and custom ended and the rights of American trade began.”

Once the war begins, the primary objective for Wilson and the U.S. State Department “was to win the largest possible freedom of trade for American citizens with all belligerents, within the bounds of neutrality.”

According to Link, that goal “soon collided with an equally powerful force, namely the resolution of the British government to use its great fleet, protector of the realm and empire, to cut off the flow of life-giving supplies to the Central Powers.”

The crisis develops when the British seize ships carrying American copper to neutral ports...

…such as Sweden, Holland, and Italy. The British then escort them to British naval stations.

Reports Link, “There the vessels and cargoes stayed, often for months at a time, as it turned out, without court hearing and sometimes without any notification to the owners.”

The State Department protests, without effect. The issue dominates Wilson’s attention as December wears on.

Through the autumn of 1914, Wilson seeks to keep the United States out of the war by embracing a policy of neutrality.

This is a policy that Wilson clings to tenaciously , but…

…determining just what is permitted and what is not under neutrality is a challenging puzzle.

Two issues stand out that stymie Wilson. One is trade on the high seas in the face of the British blockade of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Wilson wants to maintain a good relationship with Britain but he also wants American firms to continue selling non-contraband materials to Germany.

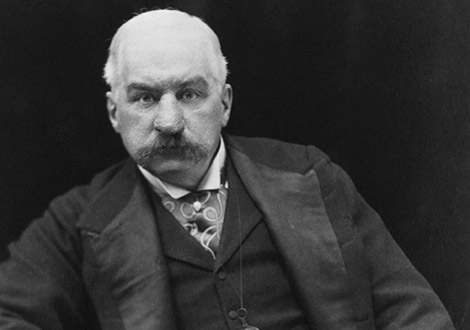

The second issue is loans. The great bankers of the day want the freedom to lend to whomever they choose. But Wilson tells reporters in October, “The administration had not changed its position on the question of loans; it still regarded loans to the belligerents as being contrary to the spirit of true neutrality.”

According to Wilson biographer Arthur Link, the bankers are eager to lend the French government $10 million, and fail to see “the subtleties of the explanation.”

The banks, led by the House of J.P. Morgan, refashion the French request as a line of credit rather than an outright loan. Over the final weeks of 1914 and into 1915, powerful American banks use this fudge to lend the belligerent nations (but mostly to the Allies) more than $80 million.

“It was easy for the administration,” writes Link, “to adhere to the policy of condoning short-term bankers’ credits while still condemning outright loans.”

But this problem is not resolved. It will return to challenge Wilson and his advisers in the coming months.