ANZACs Face Strong Turkish Defense, Terrible Terrain, Incompetent British Leadership

Special to The Great War Project.

(26-29 April) In these days a century ago, the British continue to pour troops onto the beaches of Gallipoli Peninsula in western Turkey.

The Turkish forces defending the beaches from cliffs above put up unexpectedly strong, indeed fierce resistance.

“By nightfall on April 26” [only the second day of the Gallipoli invasion] “more than 30,000 Allied troops were ashore,” reports historian Martin Gilbert. “The number of dead and wounded in the first two days of battle exceeded 20,000.”

They are mostly troops from Australia and New Zealand known as ANZACs.

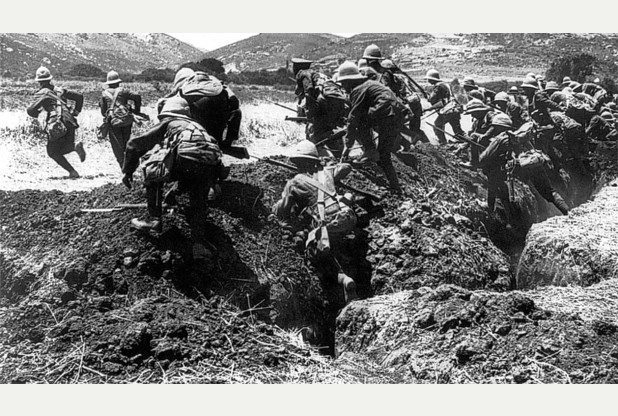

“The ANZACs knew the importance of getting high quickly,” writes war historian John Keegan, “and after an almost unopposed landing, began climbing the ridges in front of them as fast as their feet could take them.”

The attacking soldiers soon discover just how inhospitable the terrain is — in Keegan’s view, “as hostile as any defending force.”

“Organization dissolved in the thick scrub and steep ravines”…

…” Keegan writes, “which separated group from group and prevented a coordinated sweep to the top.”

Sadly, Keegan writes, “The ANZACs, clinging lost and leaderless to the hillsides, began, as the hot afternoon gave way to grey drizzle, to experience their martyrdom.”

The ultimate aim of the Gallipoli invasion is to capture the Dardanelle Straits, the narrow strategic waterway that protects the Ottoman capital, Constantinople.

Despite all the forces the Allied invasion brings to bear on Gallipoli, the invasion is not successful. “From first to last,” writes Gilbert, “the Narrows remained under Turkish control, not even threatened by infantry assault.”

Gilbert is withering in his criticism of the British generals who conceived and ordered the soldiers into the battle.

“There were moments, when incompetent and confused leadership at Gallipoli made a mockery of the bravery and tenacity of the Allied troops”

The Turks, with German generals leading the defense, “were able to keep the invading force pinned down to its two beachheads.”

As the fighting unfolds, there is much political maneuvering going on, steeped in secrecy. The Allies want Italy to join the war against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire.

With the invasion of Gallipoli, it appears “the prospect of an Allied victory,” observes Gilbert, “remained sufficiently alluring for the Italians to sign a secret treaty on April 26, committing themselves to the [Allied powers].”

The secret treaty bringing Italy into the war joins other secret treaties plotting the carve-up of the Ottoman Empire. Russia would get the great prize, Constantinople, and control of the waterways leading north to the Black Sea, giving Russia its long sought-after control of the narrow waterways to the Mediterranean.

Italy too would acquire substantial territory. “Italy’s territorial gains,” writes Gilbert, “would come both from a defeated Austria-Hungary and a defeated Turkey.” The Italians have in their sites a complexity of territories in the European Alps as well as coastal regions in what will become Yugoslavia, including many islands off the Dalmatian coast, now Croatia.

The Allies also secretly pledge to deliver to Italy substantial colonial territories in North Africa.

This is an extraordinary redrawing of the map of Europe and its adjacent territories.

It all depends on a speedy allied victory at the Gallipoli Peninsula. Prospects of this at first appear hopeful. “On April 28th a force of 14,000 men advanced two miles inland from Cape Helles,” the southern-most landing beach in the invasion. They almost reach the heights at a town called Achi Baba.

From there, writes historian Gilbert, “they would have been able to look down on, and fire on, the Turkish forts on the European shore.

“But despite repeated assaults, those heights remain in Turkish hands as did the village of Krithia below them. Since the initial landings, Turkish reinforcements had been brought up uninterruptedly.”

One other smaller unit taking part in the invasion is an all-Jewish unit put together by the Zionist leader, Vladimir Jabotinsky. He hopes Jewish contributions to the Allied invasion will advance his own cause, the establishment in Palestine of a homeland for all Jews, after the war.

Five hundred strong, it is called the Zion Mule Corps.