No Allied Reinforcements Available; British Generals Sacked.

Leaderless Allied Troops in Shock

Special to The Great War Project

(11-14 August) The Allied offensive on the Gallipoli Peninsula in northwest Turkey is proving to be a disaster.

It’s the fourth day in the battle for the heights at Chunuk Bair and Suvla Bay. The British and their allies bring 50,000 troops to the beach at Suvla Bay. By now 2,000 are killed and 10,000 wounded.

Add to that thousands more soldiers who are taken sick and have to be removed to hospital ships off shore, and the numbers now favor the Ottoman side.

Thousands of wounded and sick Allied soldiers are taken to hospitals in Egypt and Malta.

But writes historian Eugene Rogan…

...the British “had no further reserves to keep up the fight.”

“The Ottomans were also stretched to the breaking point,” Rogan reports, “but had managed to hold their positions despite losses on a par with those suffered by the Allies.”

Nevertheless on that very day, the British renew their offensive. And then for unexplained reasons, they cease their movement forward. All is confusion. The Allied momentum is stopped.

“No work was going on,” writes a British staff officer who is sent to the front to evaluate the situation, “and there was a general air of inaction. I was astonished to find that this is the front line.

“There were no Turkish trenches or Turks in sight, and only some occasional desultory shelling and sniping.”

The confusion is profound. “While I was there,” reports the same officer, “it was discovered that some troops in trenches in bushes on our left, which for some days had been thought to be Turks were in fact British.”

The following day, the Turks attack and drive the British forces back. Writes Rogan, “the Suvla and Anzac [Australian and New Zealand] offensives had ended in total failure.”

On that August 14th a century ago, the British general in command of Allied forces on the Gallipoli Peninsula delivers a report on the fighting to the British War Minister, Lord Kitchener in London. He is indignant at the deficiencies, writes historian Martin Gilbert. One full division of soldiers lands at Suvla Bay “without any artillery, no stores, and only a single Field Ambulance.”

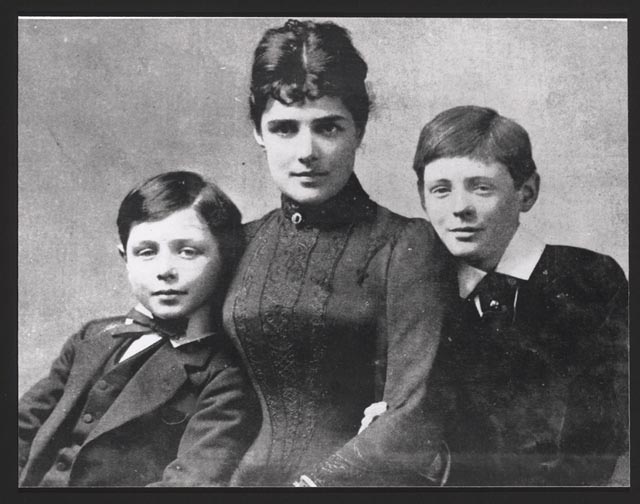

Kitchener wastes no time in acting. “I am taking steps to have these generals replaced by real fighters,” he writes that day in a letter to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

Five generals are either relieved of their commands or resign.

It’s difficult for the Allies to make sense of it all. On the scene, Churchill’s brother Jack writes to Winston, “We are all trying to understand what on earth has happened to these men and why they are showing such extraordinary lack of enterprise.”

Winston Churchill has a special interest in the battle for Gallipoli. It is his brain child, as was the naval assault on the Dardanelles Straits earlier this year a century ago. The failure of the Gallipoli battle will be seen as a failure for Churchill himself.

“They are not cowards,” observes his brother Jack. “I think it is partly on account of their training. They have never seen a shot fired before. For a year they have been soldiers and during that time they have been taught only one thing, trench warfare.”

“They landed and advanced a mile and thought they had done something wonderful. Then they had no standard to go by – no other troops were there to show them what was right….They showed extraordinary ignorance.”

According to historian Gilbert, one officer writes of the mood of the men when news of the sacking of the generals reaches them: They are “leaderless and lost in the midst of battle, and dreaming about packing up and going home.” Most of these troops, he adds, “were now in a state of acute dejection – many seemed vacant and shell-shocked – and were unfit for further service under fire.”

But writes Gilbert, “of course they had to soldier on.”