Germany Insists on Unrestricted Submarine Warfare.

Wilson Struggles to Stay Out of the War.

Special to The Great War Project

(11-14 September) For most of 1915, the United States and Imperial Germany go head to head on the submarine war that Germany is engaged in.

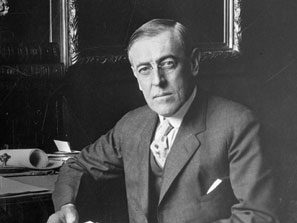

At times, especially after the sinking of the Lusitania in May, it looks like President Woodrow Wilson will break relations with Germany. Wilson seeks to curtail U-boat attacks on civilian ocean liners. Berlin resists taking that step, but fears its stance will prompt the US to join the allies and go to war against Germany.

The Lusitania disaster leaves 128 Americans dead. That ignites a tense and uncertain time in German-American relations.

Then another violent attack, on the passenger liner Arabic on August 19th sending another large ship to a watery grave.

According to historian Arthur Link…

…this “would strain German-American relations nearly to the breaking point.”

The Arabic is carrying 423 passengers and crew, among them two Americans. It is also believed to be “the heaviest carrier of contraband in the North Atlantic run.” This is her last trip, out of Liverpool. Aside from her passengers she is carrying mostly mail.

Many Americans expect President Wilson to declare war. But he is not eager.

“In a moment of obvious emotional stress,” reports Link, Wilson writes to his chief adviser Colonel Edward House.

“Two things are plain to me: 1. The people of this country count on me to keep them out of the war; 2. It would be a calamity to the world at large if we should be drawn actively into the conflict and so deprived of all disinterested influence over the settlement.”

House presses Wilson for a strong response. “In view of what has been said, and in view of what has been done, it is clearly up to this Government to act,” House writes. “The question is, when and how?”

In Link’s view, Wilson is distraught and indecisive. What he tells the Germans is not tough enough, in House’s view. Wilson favors negotiation and a peaceful solution, which he believes is possible.

The Germans do not want to see a rupture with the United States. Many German leaders believe it will be death to their cause should the US enter the war alongside Britain, France, and Russia.

Writes the German top general Erich von Falkenhayn in September, “The open partisanship of the United States against us at this time must be prevented at all costs, if it is possible to prevent it. If the limitation of the submarine war is necessary to avoid such a break, then it has to be done.”

“Whether the submarine war harms England more or less is not important, for the past six months have proved that we do not have the power to bring England to her knees.”

At this point an intense exchange of communications takes place between the US and Germany.

And then finally in September one hundred years ago, the Germans blink. Germany’s ambassador in Washington, Johan von Bernstorff writes to the US Secretary of State, Robert Lansing. “Liners will not be sunk by our submarines,” he pledges, “without warning and without safety of the lives of noncombatants, provided that the liners do not try to escape or offer resistance.”

“To Wilson and Lansing,” writes Link, “Bernstorff’s giving of what was at once called the Arabic pledge brought immeasurable relief and joy. Their long and agonizing struggle to maintain American rights on the seas without resort to war was apparently over.”

“The German government had yielded the concession that had been the most difficult for it to make.”

After the news reaches American newspapers, Wilson is hailed as a peacemaker.

Writes one newspaper editor, “Without mobilizing a regiment or assembling a fleet, by sheer dogged, unwavering persistence in advocating the right, he has compelled the surrender of the proudest, the most arrogant, the best armed of nations, and he has done it not in completest self-abnegation, but in fullest, most patriotic devotion to American ideals.”

It will take some time to determine just how successful Wilson has been.

Thank You for all your hard work !