Scale of British Surrender Unprecedented.

Soldiers Starving; Locals Hanged;

‘The Trees Dangling With Corpses’

Special to The Great War Project

(27-30 April) On this day, April 27th a century ago the British garrison at Kut, on the Tigris River in Iraq, opens negotiations with the Ottoman forces to surrender.

Three British officers, including Captain T.E. Lawrence (who will become legendary as Lawrence of Arabia,) “offer the Turks one million pounds in gold,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “if the besieged troops were allowed to leave in peace and rejoin the British forces in the south.”

The Ottoman commanding general will hear nothing of that.

“Your gallant troops,” General Halil Beg replies, “will be our most sincere and precious guests.”

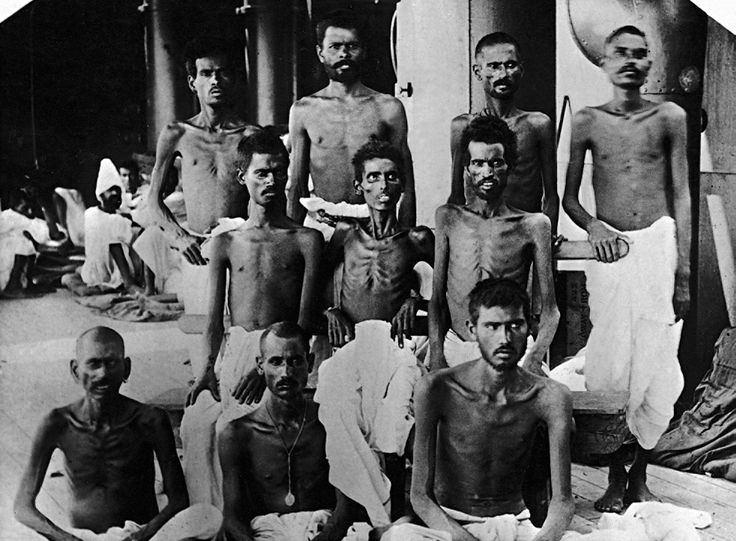

Starving Indian British troops at Kut, April 1916.

Now the British desperately hope a Russian force in neighboring Persia, approaching the Mesopotamian border, will come to the rescue. But the Russians are one hundred miles from Baghdad, and Baghdad is another one hundred miles from Kut. The Rnussians are hardly able to reach Kut in time to save the British force.

The commanding general of the British garrison at Kut, Charles Townshend, confesses that he is not of sound mind or body to carry out the negotiations with Halil Bey. “None of the British top brass,” writes historian Eugene Rogan, “wanted to involve themselves in discussions that were certain to end in an unprecedented humiliation for the British army.”

So General Townshend invites Lawrence to do the job. At dawn on April 29th, Lawrence, blindfolded, is taken across the Turkish lines, to meet the Ottoman commander.

After much discussion, the Turkish general rejects the British offer of gold.

After that there is nothing more to talk about. The British are in no position to offer anything but unconditional surrender. They are already prisoners of war, in Rogan’s view.

“The starved and emaciated soldiers in Kut assembled at midday on 29 April to face their captors,” he writes.

“The impossible and unthinkable had happened,” according to one British officer, “and one felt stunned.”

But there is also a feeling of relief. “After 145 days under siege, relentless gunfire, and progressive starvation, the British and Indian soldiers were glad to be at the end of their ordeal.”

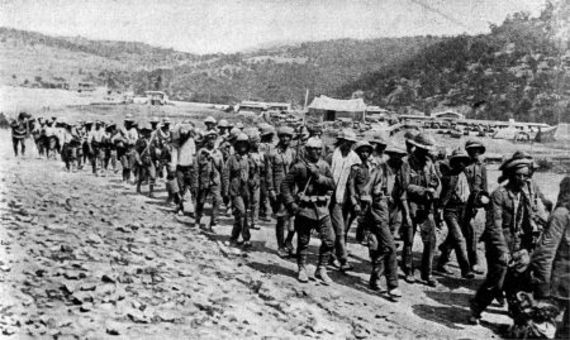

British POWs at Kut, April 1916.

“They imagined conditions as prisoners of war could be no worse than what they had already endured.”

The Turks are elated at their victory. The scale of it is unprecedented in British military history – five generals, four hundred officers, nearly 13,000 troops taken prisoner.

And what of the civilian population of Kut? “The end of the siege brought only horror to the townspeople of Kut,” reports Rogan. “The Ottomans treated them to summary justice.”

Many of those the Turks suspected of working with the British – many Arabs and Jews — were hanged and left to be slowly strangled to death.

“By the time the British troops were marched out of the town four days later,” writes Rogan, “one officer claimed…

…half the town’s inhabitants had been shot or hanged and the trees were dangling with corpses.”

As for the captured soldiers, they are about to be marched on foot to Baghdad, one hundred miles north. Not all the British and Indian troops will survive.