British Army Faces New Challenge – What’s Real Nervous Breakdown?

Soldiers Put on Trial; Face Death Sentences.

Special to The Great War Project.

(17-20 July) By this time a century ago at the Battle of the Somme on the Western Front, the British military is facing another daunting problem.

“As the fighting at the Somme continued,” writes historian Martin Gilbert, “thousands of men left the battlefield with their nerves shattered. Reporting sick and being asked what had happened, most would answer – shell-shock.”

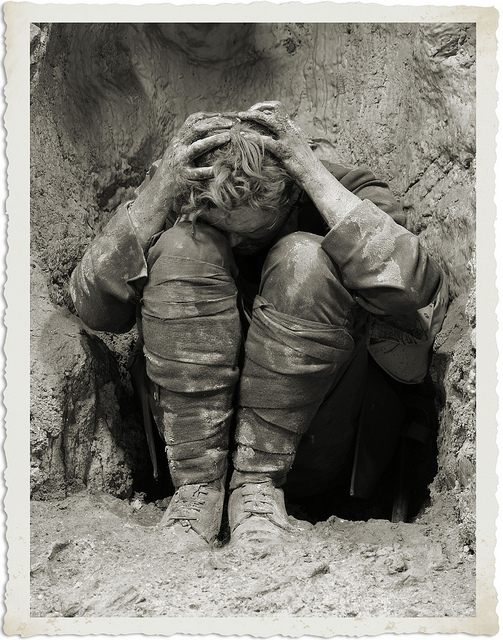

Signs of shell shock. Date and place unknown,

Shell-shock, a term that the First World War introduces, proves to be an enormous problem for the British army. “With some,” reports Gilbert, ‘this was clearly the case, but for the medical authorities it was not necessarily so.”

According to Gilbert, “the official medical history writes: To explain to a man that his symptoms were the result of disordered emotional conditions due to his rough experience in the line, and not as he imagined to some serious disturbance of his nervous system produced by bursting shells, became the most frequent and successful form of psychotherapy.”

In many cases the soldier experiencing shell-shock needed two weeks of rest and then officers sent thousands of soldiers back to the line.

Still thousands of soldiers do experience real shell-shock.

Signs of shell shock, date and place uncertain.

“It was during the Battle of the Somme, that because of the intensification of nervous breakdowns and shell-shock, special centers were opened in each army area for diagnosis and treatment.”

“The view of the military authorities, as the official medical history emphasizes, was that the subject of mental collapse was ‘so bound up with the maintenance of morale in the army that every soldier who is non-effective owing to nervous breakdown must be made the subject of careful inquiry.”

“In no case is he to be evacuated to base unless his condition warrants such a procedure.”

This is not an easy distinction to make.

“Simply put,” writes historian Adam Hochschild, “even after the most obedient soldier had had enough shells rain down on him, without any means of fighting back, he often lost all self-control.

“This could take many forms,” reports Hochschild. “Panic, flight, inability to sleep or…to walk.”

Writes one British officer, “Apart from the number of people … blown to bits, the explosions were so terrific that anyone within a hundred yards’ radius was liable to lose his reason after a few hours.”

British troops under bombardment, date and place uncertain.

Senior commanders like the Commander-in-Chief of the Somme battle, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, have little sympathy for those who suffer nervous breakdown on the battlefield. “Senior commanders like Haig,” Hochschild writes, “seldom under fire themselves, grasped little of this.

“They thought not in terms of mental illness but merely of soldiers not doing their duty.”

When some soldiers do leave the battlefield on their own without orders, they are in many cases put on trial and some are convicted. The sentence in some cases is execution. In most cases the sentences are commuted. According to the report of one such sentence, “The court recommends the accused for mercy owing to the intense bombardments, which the accused had been subject to.”

When one such case and sentence reaches Haig, he writes, “How can we ever win if this plea is allowed?”

Some of these pleas for mercy are rejected, and executions do take place.