Press Mobilized More Vigorously Than Ever.

The Electrifying Arrival of the Propaganda Film.

Special to The Great War Project.

(4-7 August) The battle of the Somme on the Western Front rages on.

“So many deaths,” writes historian Adam Hochschild, “for a sliver of earth so narrow it could barely be seen on a wall map of Europe. How was it all to be explained back home?”

The answer: newspapers. “This war cannot be fought for one month without its newspapers,” observes the well-known writer and journalist John Buchan.

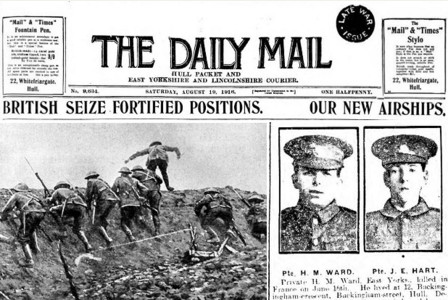

Daily Mail front page.

But only newspapers that are highly regulated, highly controlled in what they can print.

The commander of British forces at the Somme agrees – strongly. “No one was more aware of that problem,” writes Hochschild, “than the apostle of high casualties himself, Field Marshall Douglas Haig.”

At this moment in the war a century ago, Haig writes:

“A danger which the country has to face is that of unreasoning impatience.”

“Military history teems with instances where sound military principles have had to be abandoned owing to the pressure of ill-informed public opinion.

“The press is the best means to prevent the danger in the present war.”

Reports Hochschild, “And so the press was mobilized, more rigorously than ever.”

“A blizzard of regulations shaped what could appear in print, the government periodically notifying editors of topics ‘which should not be mentioned’ and wielding the ominous power of vagueness, indicating subject to be avoided or treated with extreme caution.”

“At the front,” reports Hochschild, “correspondents routinely sugarcoated British losses.

Haig outfits the correspondents well, with uniforms, drivers, escorts, and comfortable accommodations.

“At one point, pleased with the patriotic tone of their dispatches,” Haig invites the British battlefield correspondents to see him.

“Gentlemen,” he reportedly says, “you have played the game like men.”

Writes the Daily Mail’s battlefield correspondent at the Somme William Beach Thomas: “I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written.”

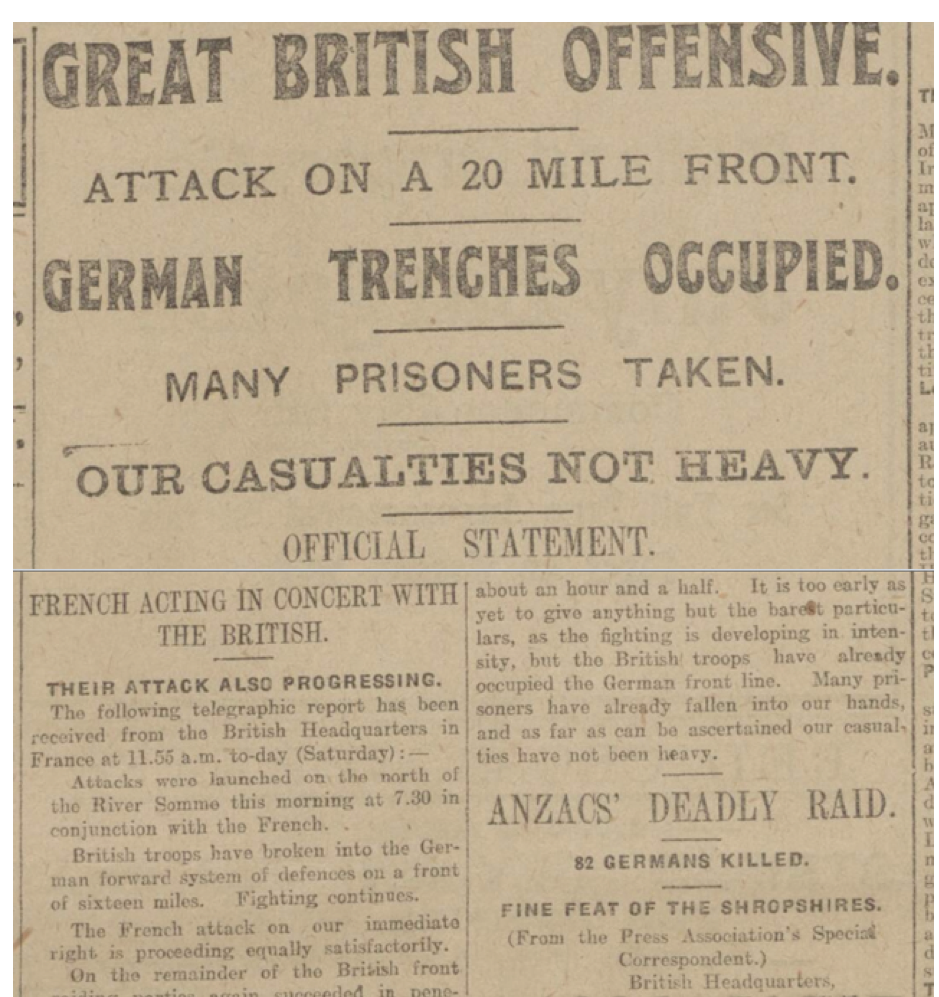

One writer who plays a key role in presenting the war to the British public is the well-known spy novelist, John Buchan.

Nelson’s History of the War, the Somme, by John Buchan.

Buchan writes for the Times and the Daily News. He also publishes installments – best sellers – for the widely read Nelson’s History of the War. The volumes on the Somme are filled with short profiles of heroes…who throw themselves onto exploding grenades, to protect their comrades.

“All of these men, clerks and shop boys, ploughmen and shepherds, Saxon and Celt, college graduates and dock laborers, all of them had served their country gallantly.”

“Every Briton should be proud of them.”

John Buchan

Buchan leaves much of the true story out, writes Hochschild. “How death or injury came to nearly half a million British soldiers at the Somme.”

“Instead, following Haig…he insisted that a shattering blow had been struck against enemy morale.”

Did Buchan believe all this? Surely not, concludes Hochschild. “He had close friends in infantry regiments who knew just how mindless the slaughter had been.”

One historian who wrote extensively about the use of propaganda in war concludes: “It was the strain of duplicity in what he wrote about the Somme that soon after the war gave Buchan an ulcer attack that required surgery.”

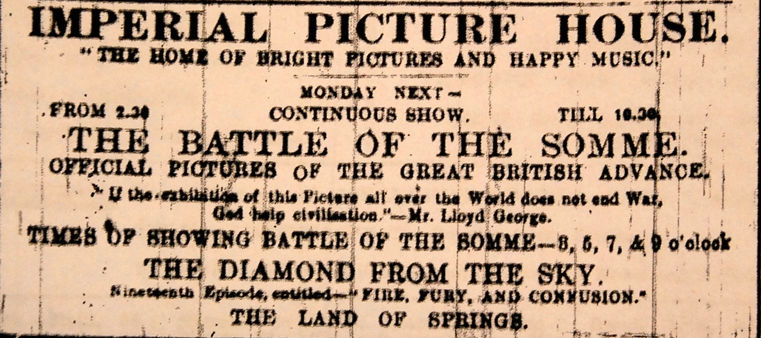

This moment in the war, August 1916, sees an important new development in the propaganda of war – film.

Cinema ticket for Battle of the Somme

The British send two cameramen into the horror of the Somme, and they come back with a 75-minute film called Battle of the Somme. It is shown in cinemas all over Britain – thirty-five movie houses in London alone. “In the first six weeks of its release,” reports Hochschild, “more than nineteen million people saw the film.”

“The film was nothing short of electrifying.”

Writes one newspaper, the film’s images “have stirred London more passionately than anything has stirred it since the war began.”