British Lick Their Wounds from Iraq Defeat,

Prepare for a Baghdad Offensive;

British War Cabinet is Cautious.

Special to The Great War Project.

(23-26 September) Despite defeats in Mesopotamia earlier in 1916 – the ignominious collapse at Kut on the Tigris River — the British are determined to reverse their losses in the desert.

Some British generals advise a passive response – lick their wounds and don’t risk further losses.

This approach only helps the Ottoman forces deployed to prevent the British from reaching Baghdad. Britain’s top general orders this passive response primarily to force the Turks to defend desert positions with troops that might otherwise be deployed to confront a Russian column poised in Persia (now Iran) to attack Baghdad.

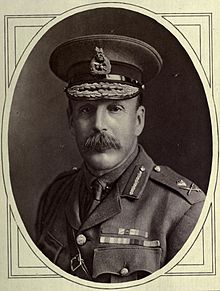

British troops at the Tigris River in Mesopotamia (Iraq).

But at mid-1916 the British “have no intention,” writes historian Eugene Rogan, “of authorizing hostilities against Ottoman positions on the Tigris.”

So the Ottomans throw everything they can against the Russian column in Persia, poised to go on the offensive to take Baghdad.

But mistakes are made on all sides, reports Rogan. The Ottomans counter-attack, going on the offensive against the Russian forces in Persia. That leaves the Ottoman position at Baghdad dangerously under strength.

According to Rogan, the Ottomans never recover from this miscalculation.

At the same time the British are slowly reinforcing their troops on the road to Baghdad with troops arriving from India and Egypt.

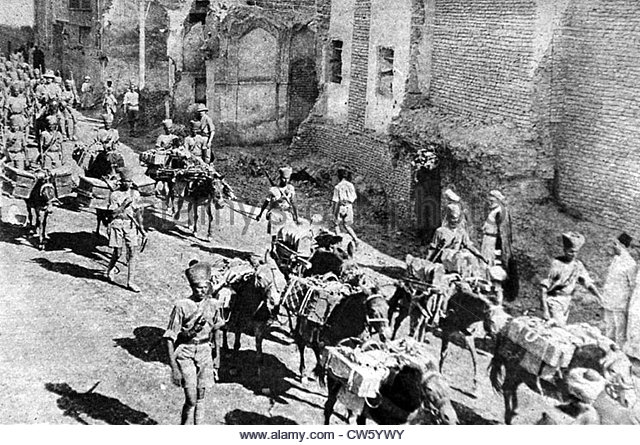

In the fall, the British appoint a new commander for the desert campaign. He is Major General Sir Stanley Maude, and Maude is determined to take the offensive on the Tigris front.

General Maude, commander of British Forces in Mesopotamia.

He manages to build up “a formidable force in Mesopotamia,” reports Rogan. Slowly some 160,00 British troops rebuild the British position.

“As Maude’s army expanded,” writes Rogan, “the Ottoman army contracted. Worn down by illness, desertion, and casualties incurred in the regular exchanges of fire,” the Ottomans suffered above all from lack of reinforcements.

The British build an advance base on the Tigris, safely protected from Turkish attack.

Rogan reports, in the autumn exactly a century ago, it is a hive of activity. Out of the range of Ottoman artillery, the British use the river and a new light railway, which they build, to speed the delivery of supplies and ammunition to their base near Kut.

Still the British War Committee in London remains cautious. They believe “Baghdad would be very difficult to take and even harder to hold,” writes historian Rogan. “given the length of the lines of supplies and communication to the Persian Gulf,” far to the south.

The War Committee dismisses the capture of Baghdad as of “no appreciable effect on the war.” But this time in the war, precisely a century, British orders are to rule out any advance in Mesopotamia.

This leaves General Maude frustrated and angry. In contrast to the generals in London, he is convinced taking Baghdad will be of real strategic value. He continues building up his forces, determined to mount an offensive for Baghdad as soon as circumstances warrant.

Baghdad, 1916.

Despite this caution, however, the overall picture for Britain in the Middle East, is improving. By this time a century ago, the Ottomans and their German allies have suffered losses in Arabia, the Caucasus, Persia, and the Sinai.

“It was obvious to everyone in Constantinople,” writes historian Sean McMeekin, “that the Turkish goal of restoring the old Ottoman borders, let alone expanding the empire further, was a pipedream.”

Thanks for covering this too-often forgotten sector of the war.