Finds Little Support, Belligerents Seek Knockout Blow;

Germans Threaten U.S. Home Territory

Special to The Great War Project

(29 September-3 October) The Germans now eye the possibility of submarine attacks on the United States.

American targets begin to attract German U-boat attention, as the underwater offensive spreads.

At the beginning of October exactly a century ago, the German Kaiser, Wilhelm, congratulates his submarine service, writes historian Martin Gilbert, for sinking one-million tons of Allied shipping, most of it British.

German U-boat sinks Allied merchant ship, date and place uncertain.

But at this moment in the war, the Germans decide to launch attacks not just on American shipping arriving in Allied waters, but “on the eastern seaboard of the United states itself.”

This decision, reports Gilbert, results in the sinking of British, Dutch, and Norwegian ships off Nantucket Island in Massachusetts.

This action directly threatens American personnel on home territory.

According to Gilbert, “The American Ambassador in Berlin, James Gerard, was even then on board ship on his way back to New York, steaming in the very vicinity of the sinkings. “I imagined,” the ambassador writes later, “that the captain slightly changed the course of our ship, but the next day the odor of burning oil was quite noticeable for hours.”

A few days later, President Woodrow Wilson meets Gerard at the White House and tells him, “I want both to keep and to make peace.”

Wilson, who is running for re-election, wants to keep the United States out of the war, but he also has ambitions to be the peacemaker, to be known as the man who ends this devastating war.

In contrast, observes historian Norman Stone…

…Neither Germany nor Britain has any inclination to follow Wilson to the negotiating table.

In fact, as this moment a century ago, a new British Prime Minister enters on the battered stage of Europe.

“A new British war leader emerged,” Stone writes, “David Lloyd George, and he wanted a knockout blow.”

Even if some of the leaders of the belligerents want to make peace, “Great wars develop a momentum of their own.,” observes Stone.

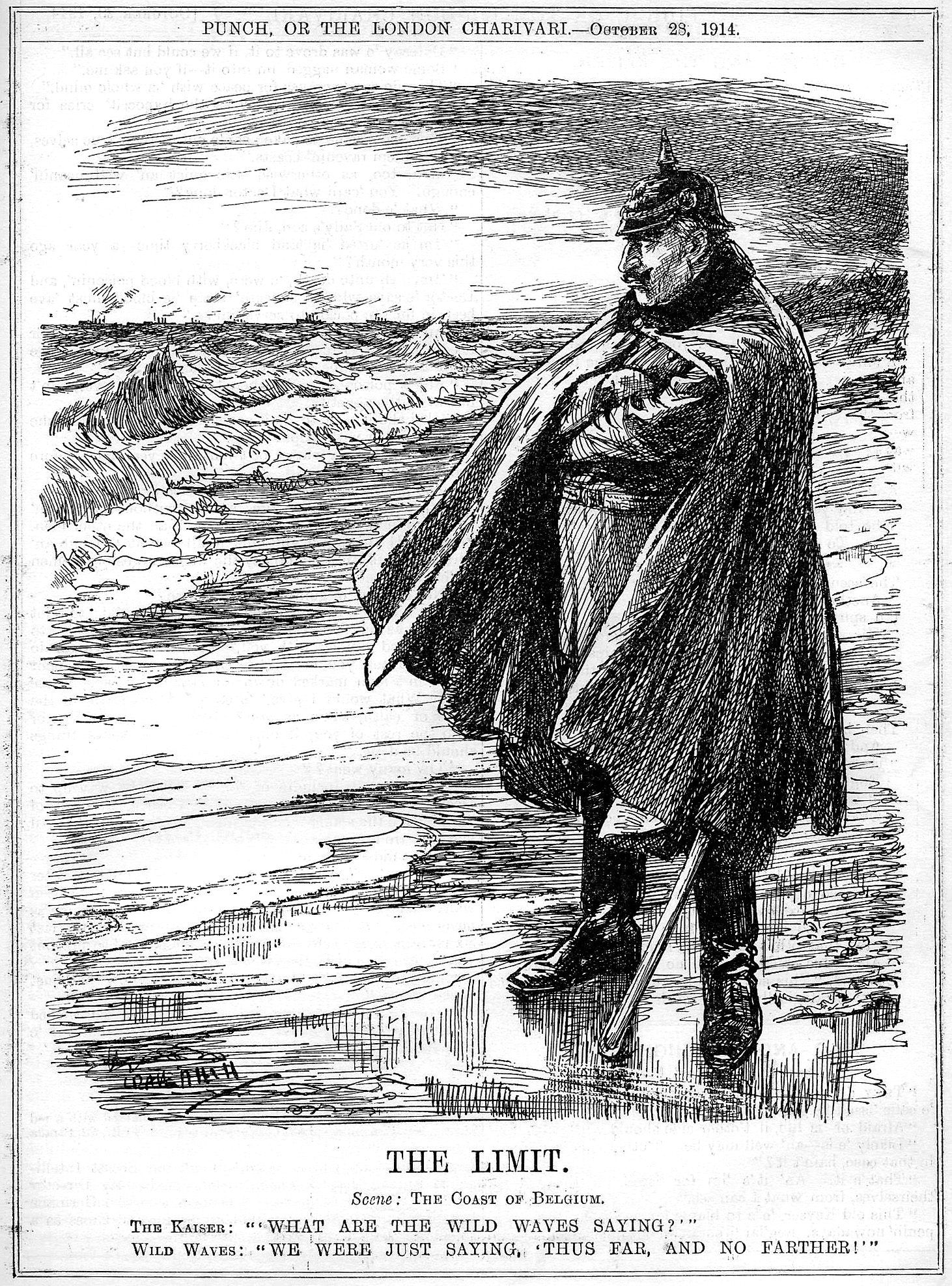

British cartoon of Kaiser Wilhelm.

“What with mass conscription, and the enormous loss of life and limb, sheer hatred of the enemy, and the emergence of a monster of public opinion that no politician could ignore, the war could not simply be ended with some recognition that it all had been a gigantic mistake.”

In fact, at this point in the war, it is still more likely that the conflict will spread and catch more nations in its bloody grip.

The new leading politicians who arrive on the scene to replace those who in 1914 allowed the war to explode and spread now believe in “the knock-out blow.”

This ensures that the war will go on with no let-up. That goes for Germany as well as Britain.

And that means “the great dramas of Verdun and the Somme,” as war historian John Keegan calls them, will continue, with no effort to end the horrible blood-letting in northern France.

Flooded trench on the Western Front.

The offensive on the Somme began on July 1st 1916. By this time, early October 1916, “the British were still trying to reach their first day’s objective,” having lost tens-of-thousands of men.

It is not just bullets and explosives that are defeating the British attacks. “Rain and mud were impeding every effort,” reports the official British historian. “The rain fell in torrents, and the battle area became a sea of mud. Men died from the simple effort of carrying verbal messages.”