Wilson Prepares Congress for Conflict,

But No Declaration Yet.

The Shell-Shocked Words of a Poet.

Special to The Great War Project

(2 April) Pro-war meetings break out in rapid succession across the United States.

“As March turned to April,” writes historian Margaret Wagner, “pro-war mass meetings occurred in Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston, Denver, and Manchester, New Hampshire.”

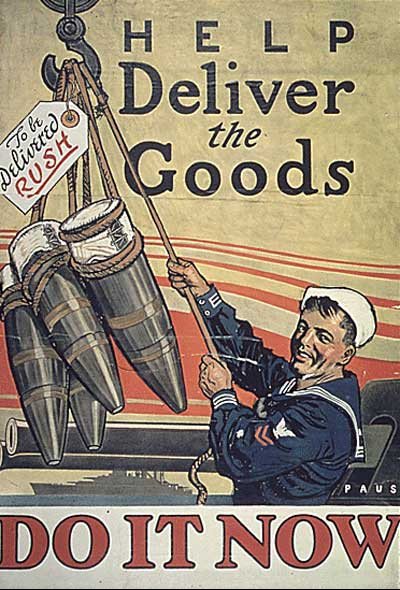

Pro war poster urging US navy to get involved.

The meetings are increasingly violent. On April 1st, reports Wagner, “a mob of nearly a thousand people surged into a Baltimore building where the former president of Stanford University, now an apostle of peace, was speaking.”

He was only saved from a mauling, reports Wagner, “when his audience stood and sang the “Star-Spangled Banner.”

Avoiding the attackers, the Stanford president escaped by slipping out unseen.

“The Germans have behaved like sin, for such is the nature of war,” writes the Stanford president that day, “But the intolerance and tyranny with which we are being pushed into war far eclipses the riotous methods which threw the Kaiser off his feet and brought on the crash in 1914.”

War is in the air.

That evening President Woodrow Wilson addresses Congress. He tells the lawmakers, “war has been thrust upon us.” Among the measures he calls for are “providing the navy with all required equipment, especially that needed for anti-submarine warfare.”

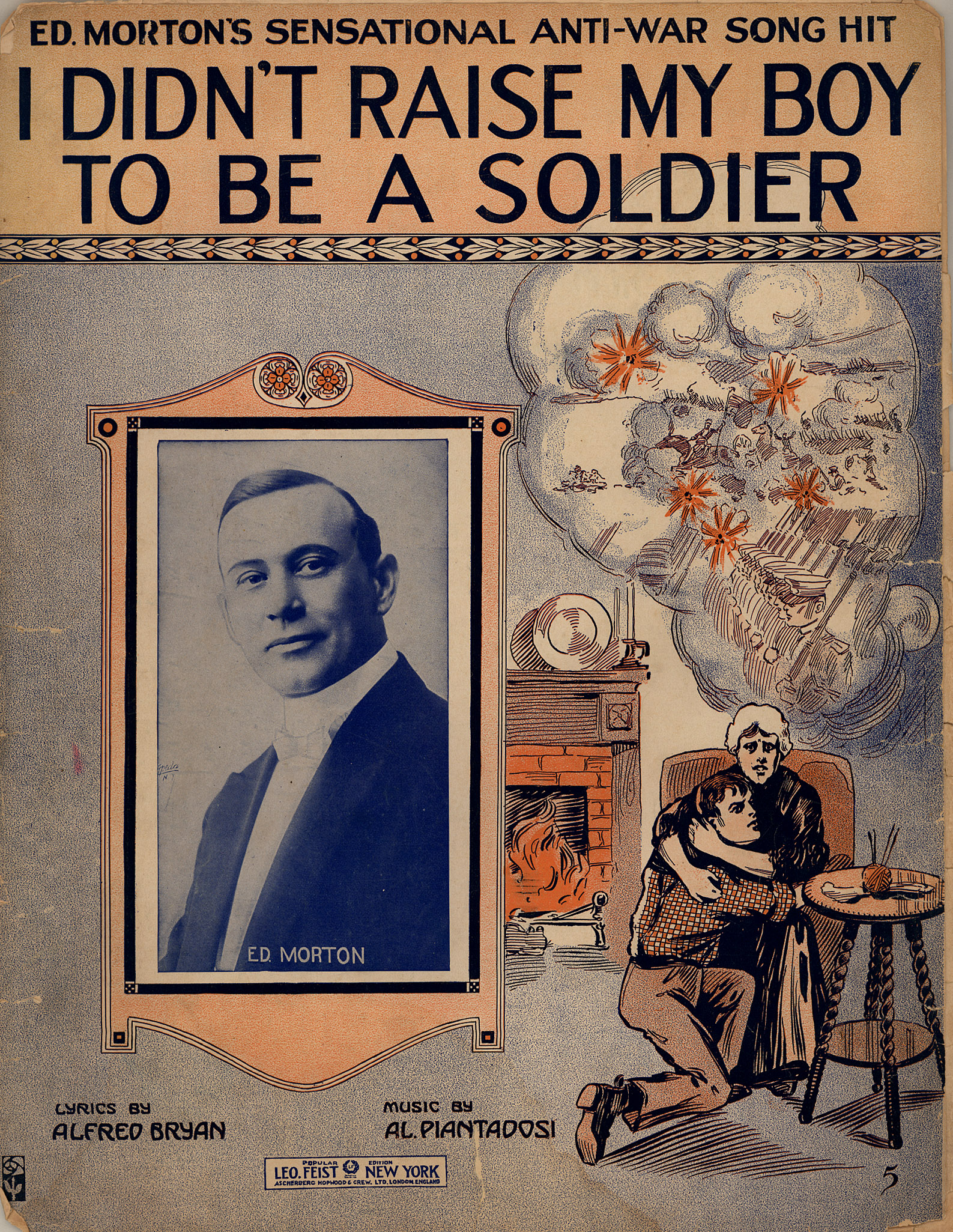

Anti-war propaganda poster, popular song.

And this measure: “Building an army of at least 500,000 men.”

Wilson ends on this ominous note. “If there be any disloyalty” he declares to approving applause, “it will be dealt with a firm hand of repression.”

Yet Wilson does not yet ask the Congress for a formal declaration of war. But the nation knows that is coming on, faster than most Americans appreciate.

Indeed, despite the tragic consequences of the war, there is still stomach — in Germany especially for more, observes historian Martin Gilbert.

On April 3rd Albert Einstein writes to a friend, from his home in Berlin “of the extreme nationalism of the younger scientists and professors around him.”

“I am convinced that we are dealing with a kind of epidemic of the mind,” Einstein writes. “I cannot otherwise comprehend how men who are thoroughly decent in their personal conduct can adopt such antithetical views on general affairs.”

“It can be compared with developments at the time of the martyrs, the Crusades, and the witch burnings.”

But despite the nature of what has taken place in Europe, the momentum toward war only grows. On April 1st “the armed American steamer Aztec was torpedoed and twenty-eight of her crew drowned,” reports Gilbert.

The next day, Wilson declares “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

Wilfred Owen’s regiment.

Meanwhile, on April 1st the poet Wilfred Owen is in action – under intense artillery barrage — near St. Quentin in northern France. Sheltering from the barrage, he falls asleep briefly but is blown awake by an exploding shell nearby.

It shakes him deeply. “When he got back to base,” writes historian Gilbert, “people noticed he was trembling, confused, and stammering.” A doctor at the front diagnoses shell-shock.

Owen is sent to a hospital away from the front where he later writes these lines of the suffering of the patients there:

These are men whose minds the Dead have ravished.

Memory fingers in their hair of murders,

Multitudinuous murders they once witnessed.