Confusion from the President and Congress

Wilson Favors Draft; Congress Against.

American Troops to France? Good Lord!

Special to The Great War Project

(15 May) Early in April 1917 the United States declares war on Germany, but from President Woodrow Wilson on down, many American leaders display an enormous naivete about what the declaration of war means.

In the early spring a century ago, according to historian Thomas Fleming, “the U.S. army numbers only 127,000, roughly the same size as the army of Chile.”

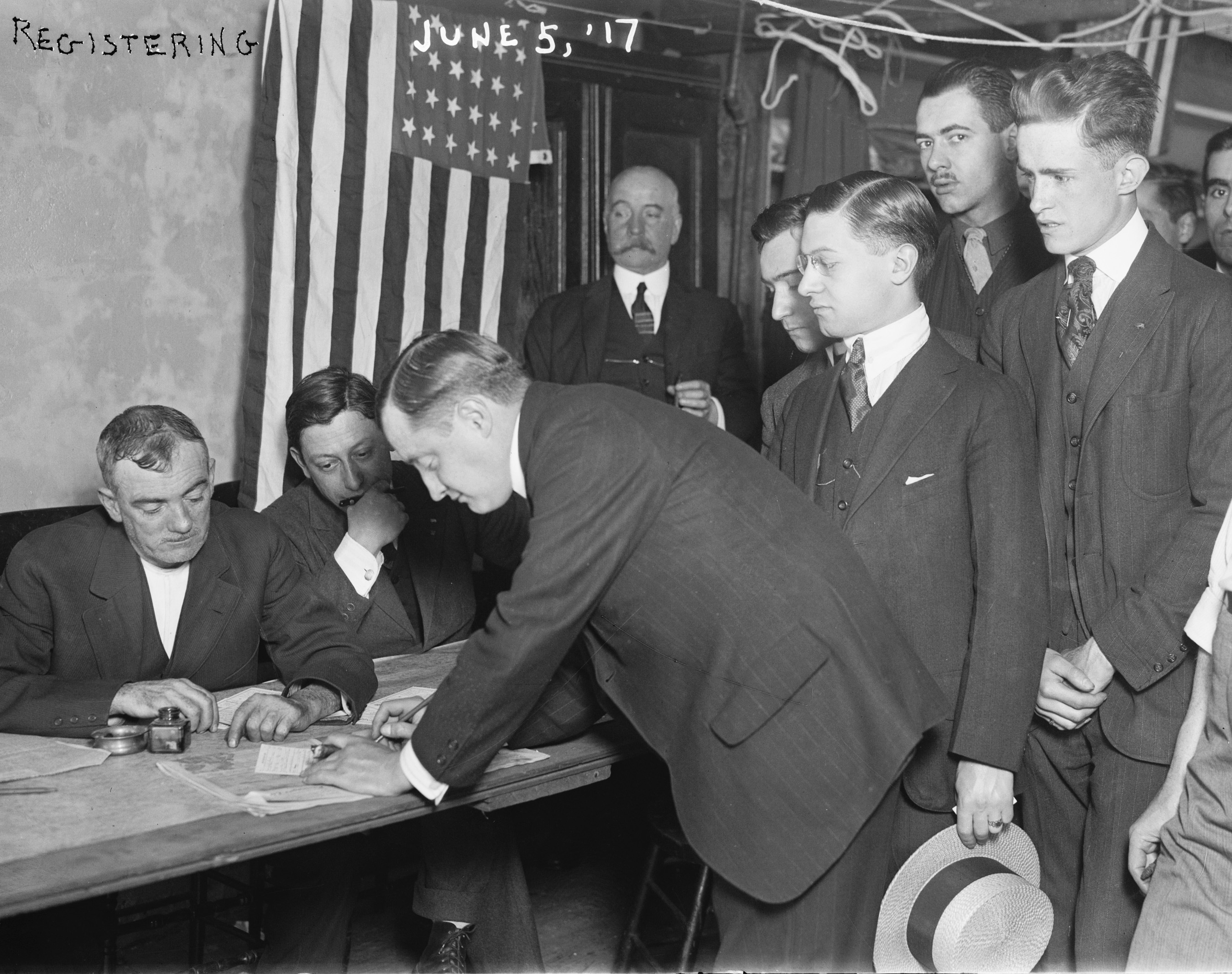

American men register after declaration of war.

And far fewer of them have the training, experience, and physical stamina needed to fight in the trenches of Europe.

Probably as many as half had never had an hour’s drill, Fleming writes.

Soon after Wilson’s speech declaring war on Germany, a War Department official testifies before Congress that the army needs $3 billion – “a stupendous amount at the time,” writes Fleming – to fight the war. In a Senate committee meeting, a representative of the War Department is asked how the army intends to spend such a huge amount.

He begins to list all of the military’s needs – building training camps, purchasing rifles and artillery, airplanes.

Then comes the shocker. “And we may have to have an army in France.”

“Good lord!’ one senior Senator blurts out, “You’re not going to send soldiers over there, are you?”

Writes Fleming, “Few comments better exemplify the almost incredible naivete that underlay the U.S. decision to declare war on Germany.”

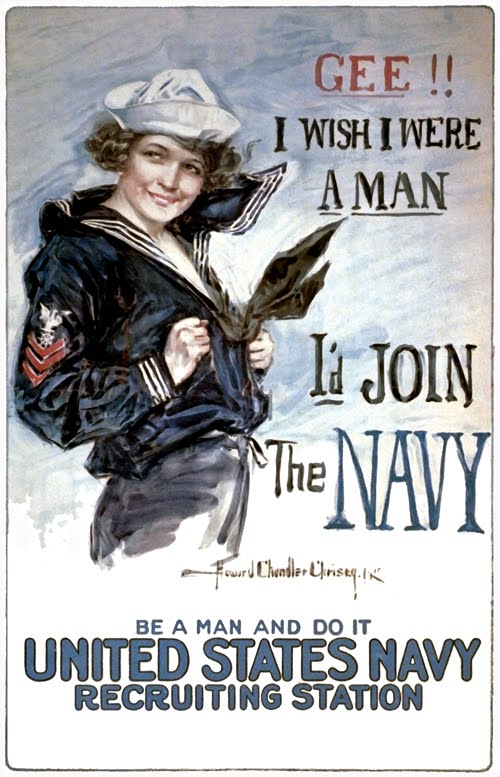

Recruiting poster after U.S. enters the war.

Are the Americans going to send troops to France? Nobody, reports Fleming “seemed to have a clue.”

Nor did President Wilson, “the supposed prophet who purportedly told a newspaper man how much anguish and turmoil the war would cause America.”

“Wilson added to this overall impression by insisting that the United States had not joined the allies…as an ally, but as an ‘associated power.’”

Initially Wilson and other political leaders favored creating an army of volunteers.

But then in May a century ago, Wilson and his Secretary of War change their position to favor conscription.

This prompted sharp disagreement in the Senate, with a majority of Senators opposing conscription, and supporting a volunteer system.

Wilson had failed to convince a majority in the Senate of the need for a draft.

In the House the Speaker “delivered a fiery denunciation of a draft,” writes Fleming.

“I protest with all my heart and mind and soul,” the Speaker declares, “against having the slur of being a conscript.”

A Georgia Senator even introduced a bill, Fleming reports, “that barred draftees from serving overseas. Throughout the South the idea of drafting Negroes and putting guns in their hands caused widespread hysteria.”

One Senator predicted the streets would “run red with blood” if Congress voted for conscription…

. Or at least if the U.S. did not try a volunteer system first.

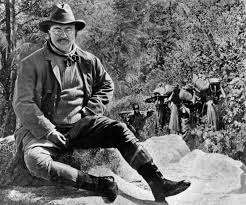

Former president Theodore Roosevelt jumped into the debate with all his rhetorical powers. Roosevelt opposed the draft and vehemently supported a volunteer system, and he goes to the White House to tell Wilson so.

Wilson is not thrilled by this visit from Roosevelt, but he listens politely, Fleming writes.

Former president Teddy Roosevelt is opposed to the draft.

It just may be that Roosevelt helped Wilson solidify his support for a draft.

“The historical record indicates,” reports historian Fleming, “that Roosevelt’s push for a volunteer division played a crucial role in Wilson’s decision to back conscription.”

I read a post like this, try to absorb or understand the comments members of Congress make and then think that it should be filed under, “The More Things Change, the More They Remain the Same”.