A British Battalion of Women, in Uniform but Not in Combat.

Frees More Men for the Front Lines.

Special to The Great War Project.

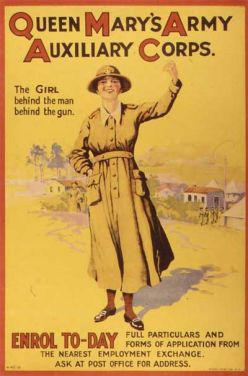

(9 July) Britain brings more women into the war at this moment in World War One when the government agrees to the formation of a Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps.

“This was the first time,” reports historian Martin Gilbert, “that women were to be put into uniform, and sent to France, to serve as clerks, telephonists, waitresses, cooks, and as instructors in the use of gas masks.”

The Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps.

In the British Army, there is the tradition that only men, writes Gilbert, could become officers. So women in charge of their units are given the rank of “controller or administrator.”

“The principle underlying the establishment of the Corps was the need to release soldiers who were doing menial jobs in Britain and France, for active service at the Front.”

Of course, women are already working in the war effort in enormous numbers, in munitions factories across Britain. The patriotic call is as strong as it is for the men of Britain, even though “long hours, acrid fumes, and low pay” characterize the conditions that women are working in.

Women in the munitions factories.

The appeal to them is powerful: “The situation is serious, women must help to save it,” so goes one of the banners appealing to women to join the war.

“At Gretna in Scotland,” writes Gilbert, “11,000 women were employed in the national cordite factory.”

“Women played an essential part in providing the necessary munitions of the war.”

“The dangers were ever present.”

“Women working with the explosive TNT were jocularly referred to as canaries because of the yellow discoloration of the skin, a symptom of TNT poisoning.”

Many women died of various ailments and from explosions. In just one single incident, scores of women are killed in an explosion at Silverton in East London when,,,

“an accidental fire ignited fifty tons of TNT, devastating a square mile of London’s East End.

This episode, according to historian Gilbert, caused more destruction than all the First World War air raids on the capital combined.”

Munitions factory in London.

The factory happened to be owned by a company with a German name. As a result, Gilbert reports, “there was an intensification of xenophobia, a result of the German origins of the owners.”

In France too, there was a similar increase of the production of war munitions, also involving women workers – “thanks in part,” writes war historian John Keegan, “to the mobilization of women for factory work.”

The output of explosives in France had grown six-fold since the beginning of the war.

There are also developments involving women on the Eastern Front. Among the Russian units still in action, was the 300-strong women’s battalion known as the Women’s Battalion of Death. Some of them saw combat.

“According to the popular Russian accounts at the time,” reports Gilbert, “the battalion captured 2,000 Austrian prisons.”

Russian women’s battalion.

One British nurse wrote of this women’s battalion: in honor of those women volunteers, it was recorded that they did go into the attack; they did go over the top, but not all of them. Some remained in the trenches. Some suffered shell-shock, desperation, and paralyzing fear.