Representatives from Most of the World’s Peoples.

The Allies Want Payments,

Wilson Wants the League of Nations.

Special to The Great War Project.

(21 January) On January 18th 1919 in the gilded Salle de la Paix of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the Quai d’Orsay, the Paris Peace Conference finally begins.

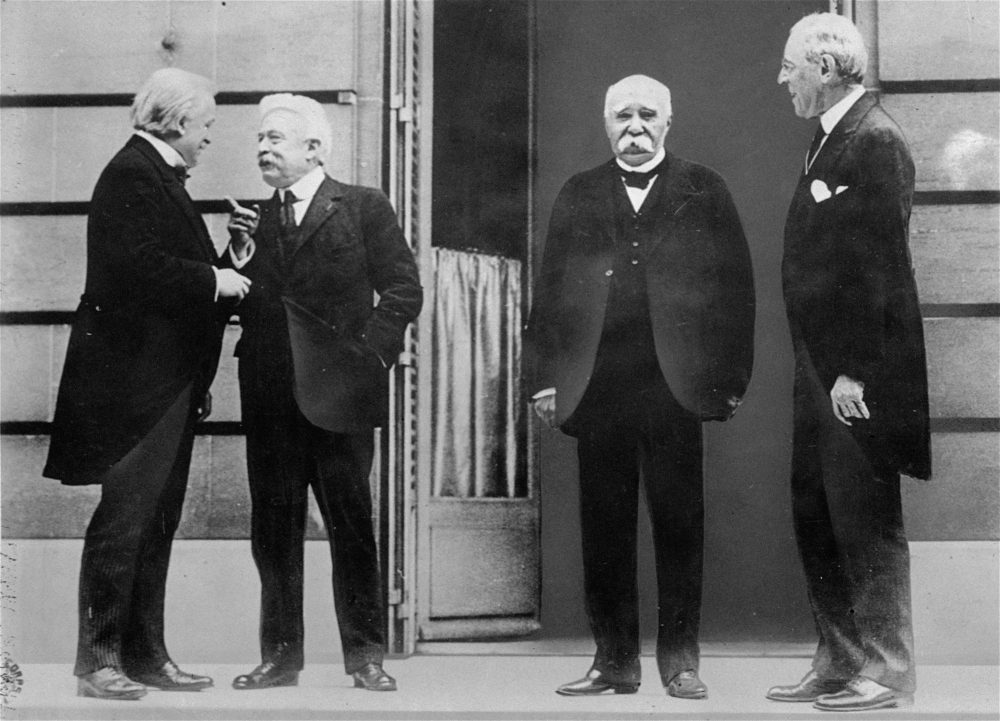

From left: Britain’s Lloyd George, Italy’s Orlando, France’s Clemenceau, and President Wilson of the US.

So reports historian Thomas Fleming: “Bearded pudgy Raymond Poincare, the president of France, opened the first plenary session with a speech that he read in a monotone, perhaps on the assumption that only a small percentage of the room understood French.”

“Before him around a horseshoe-shaped table sit representatives from thirty-two Allied and associated states representing about 75 percent of the world’s population.”

“Absent from the table were any representatives from Russia, or from Germany and its allies.

“Russia’s Bolshevik rulers had refused to come. The enemy had not been invited.”

The French president’s speech had worrisome overtones for true believers of the American president’s so-called Fourteen Points, the goals President Woodrow Wilson had mapped out earlier in the war.

It also reveals why the French had delayed the opening date of the peace conference.

The French president declares: “On this day forty-eight years ago, the German Empire was proclaimed by an army of invasion in the Chateau at Versailles…Born in injustice it has ended in opprobrium.”

This is a reference to Germany’s occupation of French territory in 1870 in the Franco-Prussian War. Poincare had made this lost territory the centerpiece of his political career.

“Poincare was the architect of France’s pre-war alliance with Russia and Britain, which had convinced the Germans they were being encircled as a prelude to extermination,” Fleming observes.

“You are assembled to repair the evil this occupation has done,” Poincare continued, “and to prevent a recurrence of it.

“You hold in your hands the future of the world,” he declares.

After a moment of embarrassed silence, President Wilson rises to nominate the French prime minister Georges Clemenceau as chairman of the peace conference. The British prime minister David Lloyd George follows with a second motion.

Clemenceau’s opening remarks go to the heart of the peace conference.

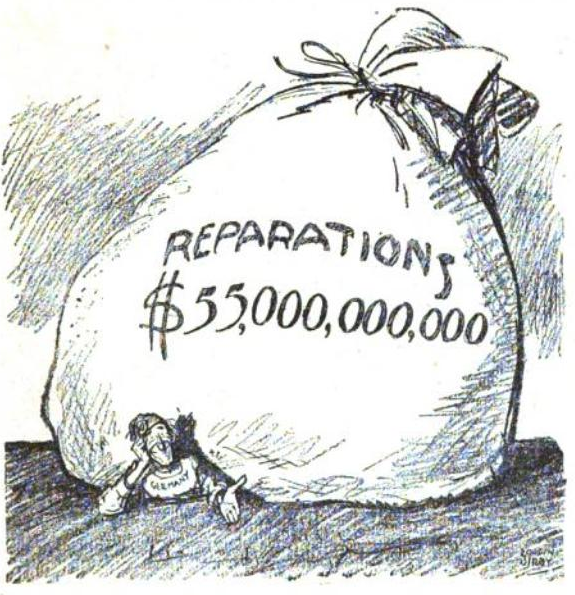

“The participants’ task,” Clemenceau declares, “is to decide who is responsible for the war, who should be punished for it, and how much Germany should pay for the terrible depredations that had devastated and ruined one of the richest regions of France.”

Fleming notes,

“There was not so much as a mention of a league of nations” Wilson’s key issue.

Observes historian Fleming, “This was confrontational diplomacy of the most blatant kind, a veritable declaration of war on Wilson’s Fourteen Points.

From left: Lloyd George, Clemenceau, Wilson.

Wilson came to have no illusions though about what the other Allied powers wanted from the conference: loot, payments from Germany, gold, and territory.

Wilson concentrated his mind on this primary goal, according to Fleming: winning support for the league, which would be intertwined with the peace treaty.

Paris is awash in “experts,” with each major power bringing to Paris the staff to negotiate the details. The American delegation numbers more than a thousand.

But according to historian Fleming, no one had thought to create an agenda ahead of time.

Yes, it’s just my opinion, but Wilson always thought of himself as the smartest man in the (or any) room and yet he was out-maneuvered over and over again.